Beirutis have every reason to fear the cycle of poverty they face – just look at Lebanon’s history

The Beirut of 2020 is the same city which endured Ottoman military ferocity, Allied blockade and locusts more than a hundred years ago. Robert Fisk tells the people’s story

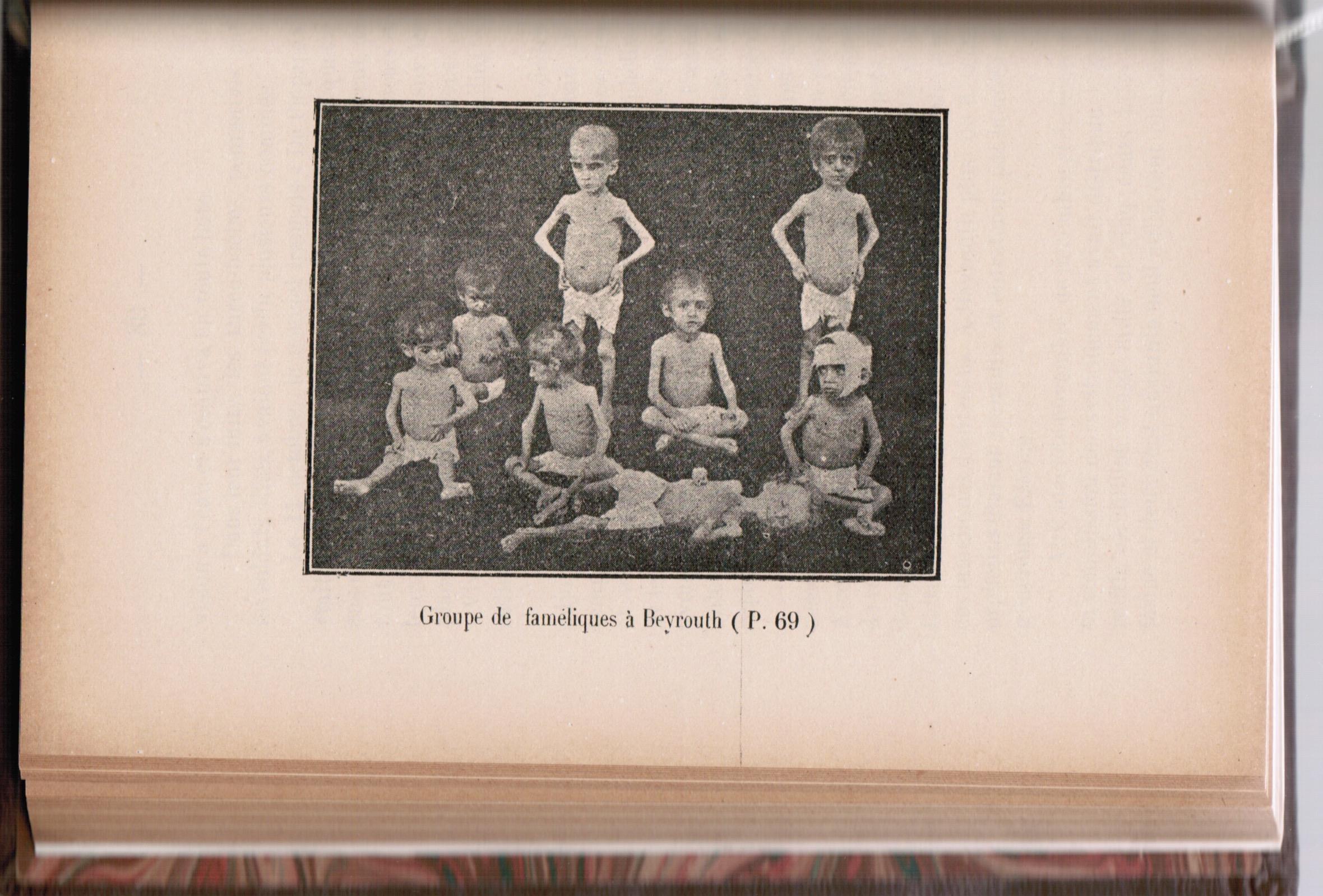

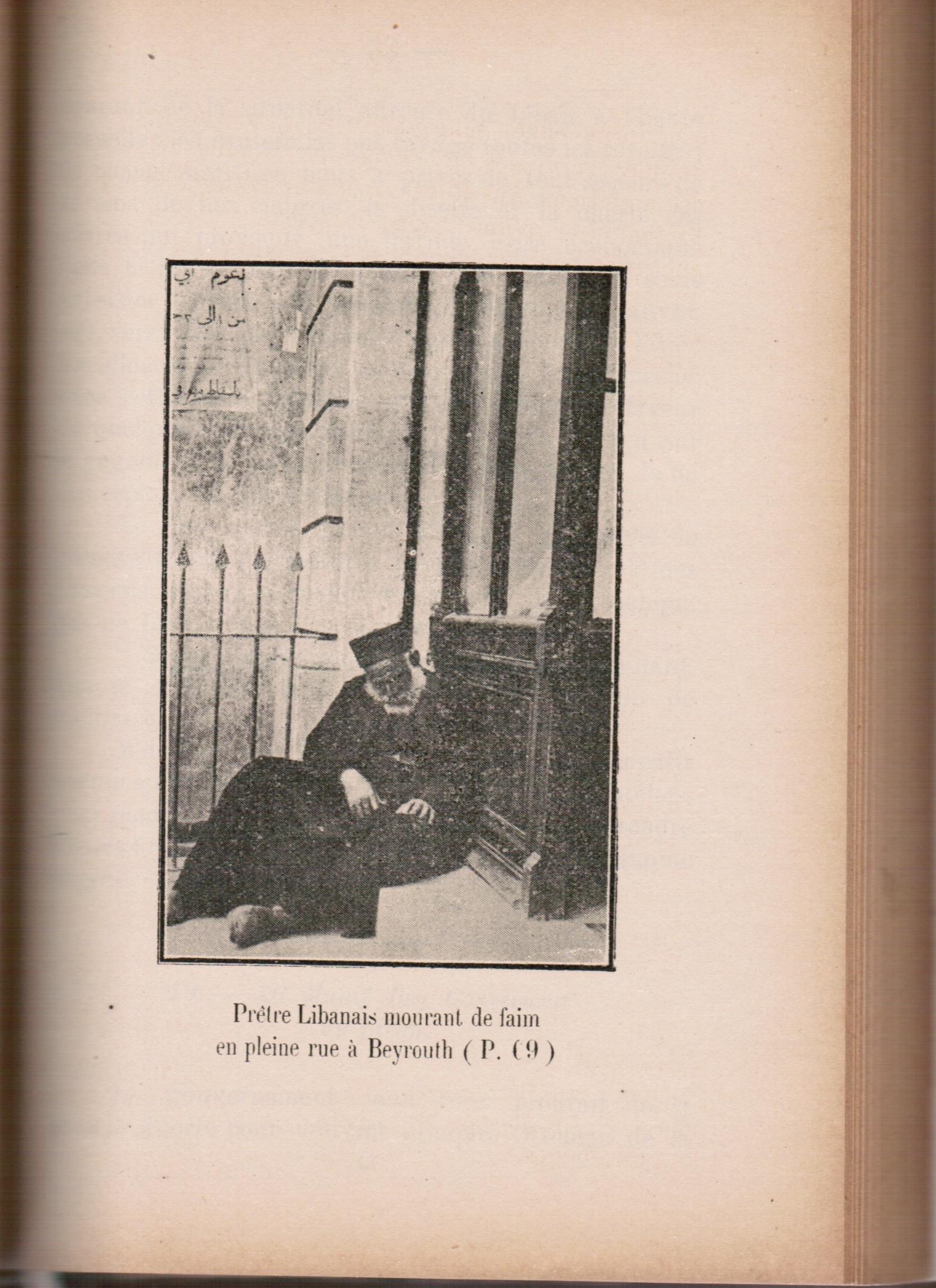

The pages are so fragile that I turn them with infinite care, blowing apart those which adhere to each other lest they tear. An unknown hand – almost a century ago, I think, when my book was new – gently repaired with paste the final page of Fr Antoine Yammine’s frightful account of Lebanon’s Great Hunger. It is a ghost-book for the present day; my own edition was published in Cairo in 1921 and contains photographs which editors might even now blanche to look upon. I long ago bound its 212 pages in crimson leather, the work of Beirut’s oldest bookbinder who worked in a narrow shop not far from the city centre where many of the volume’s events took place.

I don’t begrudge today’s Lebanese their fears. The Beirut of 2020 – corruption and revolutionary anger, bankruptcy, unemployment and hunger notwithstanding – is the same city which endured Ottoman military ferocity, Allied blockade and locusts more than a hundred years ago. And the great-grandparents of families who still live along the Lebanese coast and in the mountains above the capital were dumped in the mass graves of sand beneath which Corniche Mazraa, that canyon of Beirut traffic, now stands.

I remember, when I first came to Beirut, meeting old folk who remembered their parents telling them of bodies in the mountains, around Bikfaya and Broumana and in the Chouf, who were buried with mouths coloured green because they had been trying to survive on stinging nettles when they starved to death. Some 70 years earlier, victims of the Irish famine also vainly tried to eat nettles to save their lives.

The Great Lebanese Famine — majaea Lubnan in Arabic – had other parallels with the Great Famine in Ireland, or an ghorta mor. The Irish suffered the potato blight. Amid their own famine – mostly man-made by Ottoman depredations on food supplies for its First World War armies and Allied naval blockades on the Levant – the Lebanese suffered plagues of locusts so terrible that they darkened the sky.

The country’s most famous poet, Kahlil Gibran, in exile in America, wrote of how “my people died of hunger, and he who/ Did not perish from starvation was/ Butchered with the sword”. He, like many other Christians, believed the death of 120,000 Lebanese, perhaps as many as 200,000 (half the estimated population) was part of a genocidal drive by the Ottoman Turks to destroy the Christians of what was then called Mount Lebanon.

“80,000 have already died,” he wrote in 1916, associating the catastrophe with the genocide of a million and a half Armenians at the hands of the Turks the previous year. “Thousands are dying every day.”

Fr Yammine wrote of corpses collected in the streets of Beirut in municipal carts, the still-living sometimes buried alive with the dead on the old seafront behind Ramlet el-Baida, of child prostitution, of a population not only enduring mass hunger but afflicted with cholera and typhus. Cannibalism was reported in Tripoli, Beirut and in southern Lebanon.

When British troops eventually entered Lebanon from Palestine in 1918, they were ordered to double march north with food for the people of the capital. One British soldier recorded a starving man in the village of Damour, then a Christian town south of Beirut, crawling from his front door on all fours like an animal to greet him.

But Lebanese today might find something faintly familiar in the stories of rich Beirutis who continued to eat well and party amid this disaster, and of money-lenders, “traders in souls”, whose interest rates rose from 25 per cent to 150 per cent during the war. Corruption indeed. Speak not these truths to the bankers and exchange dealers of Beirut today.

Fr Yammine wrote of the “food” to which the people of the countryside turned to survive. “They nibbled on the grass of fields, on brambles and would soon die, wasting away, knees, shoulders and elbows arthritic, searching for barley grains amid animal excrement…”. Houses fell to ruin over the corpses of entire families, he recorded. Others survived; Howard Bliss, the president of the American Protestant College – today, the American University of Beirut – saved students from military service in the Ottoman army.

But when Jemal Pasha – the overseer of the 1915 Armenian genocide and one of the most prominent Ottoman leaders in Beirut – turned up at the college in 1917, “we had a very delightful visit from His Excellency Mohamed Jemal Pasha,” Bliss wrote. This dangerous friendship may have helped save the college but remained, in the words of one local historian of education, “controversial” in the years which followed.

A year before Bliss expressed his views, Jemal Pasha had hanged nationalist patriots in the centre of Beirut, the area now called Martyrs’ Square; he himself was known as “Al-Saffah”, the Blood Shedder, when he left what was still Greater Syria in 1918, although scholarly debate continues about his responsibility for the Lebanese famine.

An Anglo-French naval blockade on the coast undoubtedly caused much starvation, accompanied by the Ottoman seizure of crops and the Turkish refusal to allow trains to bring wheat from Syria to Lebanon; rail traffic was for Ottoman military use only. Young Lebanese were forcibly enlisted into the Ottoman army – the father of my own elderly former driver in Beirut was arrested and ordered into the Ottoman army on his wedding day – and thus could not help their families when starvation struck them down.

An American woman resident in Beirut described how she “passed women and children lying by the roadside with closed eyes and ghastly, pale faces. It was a common thing to find people searching the garbage heaps for orange peel, old bones or other refuse…”. Another American woman, with the Beirut chairman of the American Red Cross, travelled for two days across Lebanon in 1917 and found “whole families writhing in agony on the bare floor of their miserable huts…”. Every piece of their household effects had been sold to buy bread, and in many cases the tiles of the roofs had shared the same fate.

Foreign residents of Beirut would later describe how they closed their windows at night so as not to hear the pleas of “jau’an” (“I am hungry”) cried repeatedly by dying children. Among the earliest souvenirs to be hawked among the victorious Allied troops when they reached Beirut was a horrific picture postcard depicting the starving children of a 1915 city orphanage, their matchstick limbs and skull-like faces appended to huge, distended bellies.

It was not difficult to see how the mild and philosophical Gibran could also refer to the Ottomans as “monsters” amid this hell-on-Earth in his poem “Dead Are My People”. The Lebanese, he wrote, “died because the vipers and/ Sons of vipers spat out poison into/ The space where the Holy Cedars and/ The roses and the jasmine breathe/ Their fragrance”. The Levant had experienced starvation in previous years – the Lebanese who drowned on the Titanic (their names still etched on the ship’s memorial in Belfast) were themselves fleeing a 1912 famine – but nothing on this scale.

And yet Lebanon’s travails were forgotten by the rest of the world in the years to come – as its 1975-1990 civil war already has been, and as its present calamity may be ignored amid the ruins of neighbouring Syria. The French foreign minister, who visited Beirut this month to tell its pitiful government that its fate was in its own hands, might have remembered that French warships helped to impose the sea blockade which prevented food supplies reaching Beirut during the First World War.

Ottomans and locusts were not the only nations responsible for Lebanon’s Great Famine. France’s fatalities at the place of its most terrible Great War martyrdom – Verdun – came to more than 162,000; which, give a few thousand more or less, is what Lebanon suffered at exactly the same time. No wonder the country’s people now fear the very word “famine”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments