I took a few tentative steps into a virtual world – and it scared me

Could this technology supplement other forms of storytelling alongside books, films and theatre? Perhaps, argues Sean Russell. But he sees a different future

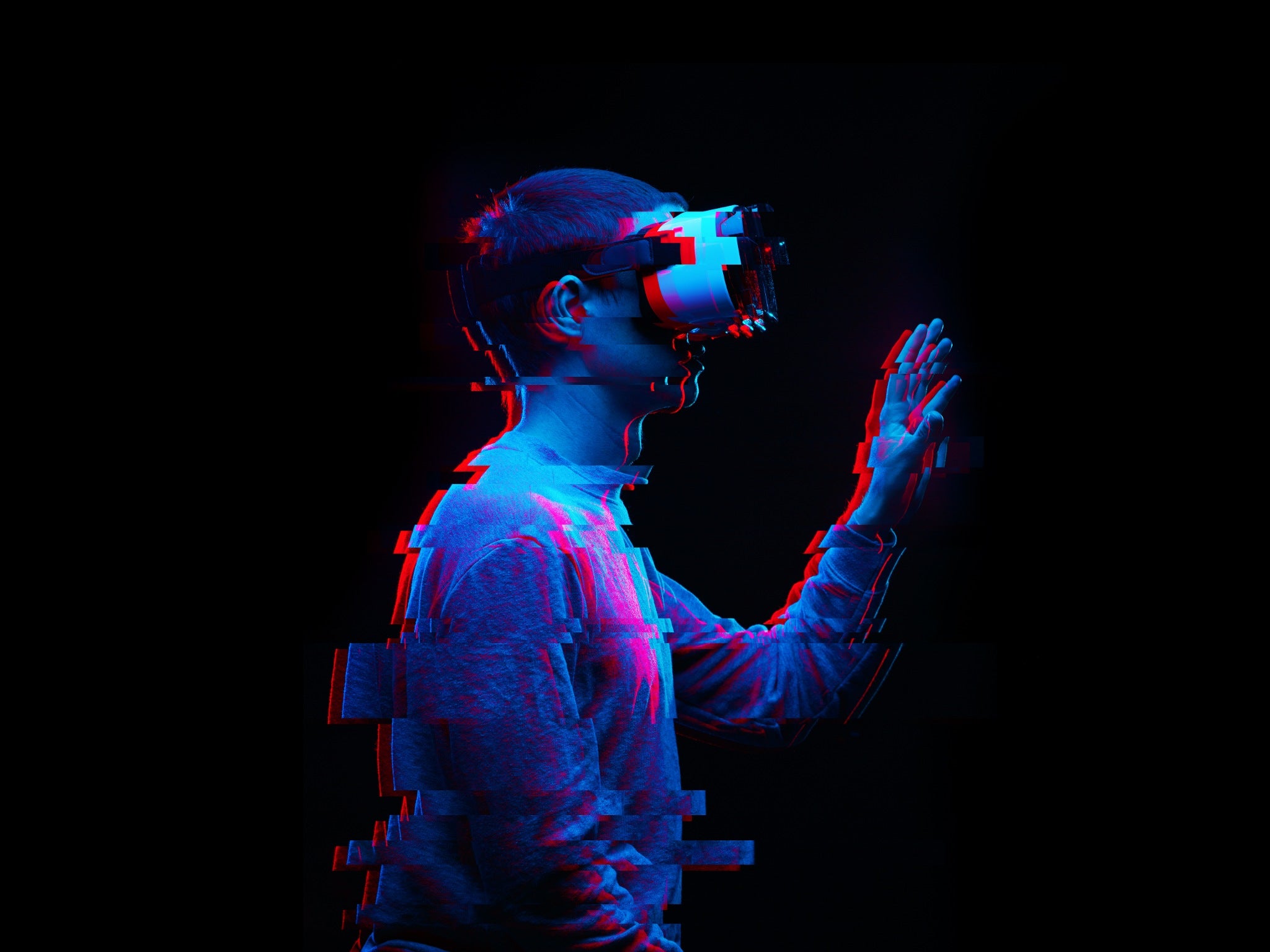

I've seen the future – I think – and it was terrifying. Not initially, initially it was enjoyable, too enjoyable, perhaps. I strapped on a headset, attached a few gizmos to my arms and legs, and then was transported to a ball in Paris, along with another nine people, when really we were just in a basement in the Barbican Centre.

I was immersed entirely. As we rode a train, wind blowing gently as it might in “real” life, we arrived at Mimi’s, an early-mid 20th century venue, and I was filled with joy, real, utter joy. I felt like I was there.

David Chalmers, an Australian philosopher who specialises in consciousness and techno-philosophy, argues that what exists in virtual worlds is in fact real. Digital, yes, but nonetheless real. You experience it, it is separate to you and it can add value to a life. This, then, is where the terrifying part comes in.

The magnificent – and award-winning – Le Bal de Paris, choreographed by Blanca Li, takes you from a ballroom, to a garden party and then finishes at Mimi’s. You dance and interact with the people around you, and your virtual body moves as if it were your own (with the exception of your hands which remain static). You can look in the mirror, choose whichever Chanel tuxedo or dress you want, and which animal mask to wear to the masquerade. You ride on a boat and a train and feel the wind. You enter into a garden maze and actually smell the roses. And then, when you take off your mask at the end, it’s over, you’re back in the basement in grey, old London.

It takes a while to adjust back to the world. Everything seems strange, like when you wake up from a particularly realistic dream and for that moment are unsure what is real and what is not. I also felt that I didn’t want to leave Paris.

For me it was Paris that captured me, for others it might be anywhere else or any other time. We are in the early days of virtual reality and there are not many fully immersive experiences. But perhaps one day, not so far away, you could choose to be in Ancient Rome, rubbing shoulders with Cicero. Or maybe in Renaissance Florence with Lorenzo de Medici. Whatever it is for you, there will soon be somewhere that makes you feel like you don’t want to leave the virtual world. This then offers a glimpse of the future.

However, the tech involved is still clunky and big. The image you view is slightly pixelated and your virtual hands don’t move even if your arms do. But I was still absorbed into feeling real feelings, into that slight moment of joy as we pulled up at Mimi’s in the Parisian night. So what will this technology be like in 10 years? I was also left with this thought: is there a chance those who can afford it may plug themselves into virtual worlds while others are left behind? I'm certainly not the first to think it.

It is very easy to drift into cynical, dystopian thinking when dealing with new technologies. Plato, for example, believed that the invention of writing was harmful – that it removed the art of oratory dialogue and the necessity to learn ideas by heart. Meanwhile, I subscribe to contemporary British philosopher John Gray’s assessment of so-called “progress” – that humans are fundamentally imperfect therefore anything we create will be imperfect also.

For example, the world wide web in its earliest days was envisioned by IT pioneer Ted Nelson as becoming a way of showing interconnection – particularly of writing – through linking things together. An encyclopaedia with hyperlinks. Information put alongside its sources. Basically, a glorified – and potentially more trustworthy – Wikipedia. But humans created the web, so it has gone in directions that very few of us could have fathomed. No doubt the internet is just a tool and is therefore neutral in itself, but the way humans have used it has has magnified what Sigmund Freud called “the narcissism of small differences”.

Returning briefly to Plato in Phaedo, the philosopher says that the inventors of new technologies may not be the ones who understand what the impact of those technologies might be on society.

This is why I struggle to see beyond a dystopian future when it comes to virtual and augmented reality. Could this technology supplement other forms of storytelling alongside books, films and theatre? Perhaps. I don’t deny it’s possible. In fact, right now – when also combined with current computational limits – the very physical limitations mean that it has few possibilities.

We were in a small room in the Barbican, around which we could walk and interact with each other. But whenever we needed to move rooms, or settings, we were either transported by a magically moving platform, train or boat; or we were led around a maze of corridors, presumably walking around the room in a sad conga without music.

There are also sensory limitations. Apart from the other real people, you were not able to touch anything you saw. So for now virtual reality remains a bit of entertainment, like watching a movie – you are still separate to the virtual world.

But what if you could plug the virtual world directly into your brain and you could feel everything and move around at will? Yes, yes, very The Matrix, I know. But this technology is not as far as you might think. Especially since Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerburg are believers in this sort of future, and Chalmers sees direct brain links within the next hundred years. Then the real ethical questions begin.

If we accept what Chalmers says in his new book Reality+, that virtual worlds are genuine worlds where one can live a meaningful life, then what’s to say we are not already in a simulation?

In fact, Chalmers himself roughly calculates that there is a 20 per cent chance this is the case. That we are simply now building simulated worlds within an already simulated world. The Australian philosopher believes there is no way of proving that we are not in a perfectly simulated world – there must be a biological world somewhere, it just might not be ours.

Another philosopher, Oxford University’s Nick Bostram, offers three scenarios: The first is that humans would go extinct before we could possibly get to that level of simulation, therefore we are unlikely ourselves to be in a simulation. The second is that we will have the capability to create such worlds but for whatever (probably ethical) reason will choose not to. And the third is that humans will create that technology and run many different simulations and therefore we may already be in one since we’d have proved it was possible to build. Since our understanding of consciousness is close to zero, we cannot currently rule this out.

So who’s to say we are not already in a virtual reality world which we’ve manage to ruin by emitting so much CO2? That would be an inception of virtual worlds, if you like, building a virtual world within a virtual world, and somewhere there are those living in a real biological world outside the system.

I for one am terrified by this all. The future ethical reasons alone are scary, let alone the lofty implications that we may all already live in a simulation.

But perhaps I am not the audience for this sort of technology and I’m just being too cynical. It’s just that I’m the sort of person who likes vinyl records, and physical books and newspapers and magazines. I still wish the internet was just a massive Wikipedia and that social media didn’t exist.

But then again if we’re in a simulation already, what does any of that mean? Wouldn’t my record collection in a virtual world be just as real as in this one? Oh no, I’ve got myself in a loop.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks