Poverty and crime ‘linked to differences in newborn brains’, study says

Stress of social diasadvantages on mothers could have long-term effect on child’s development, Sam Hancock reports

Environmental factors such as poverty and crime can influence the structure and function of babies’ brains before they have even been born, according to a new study.

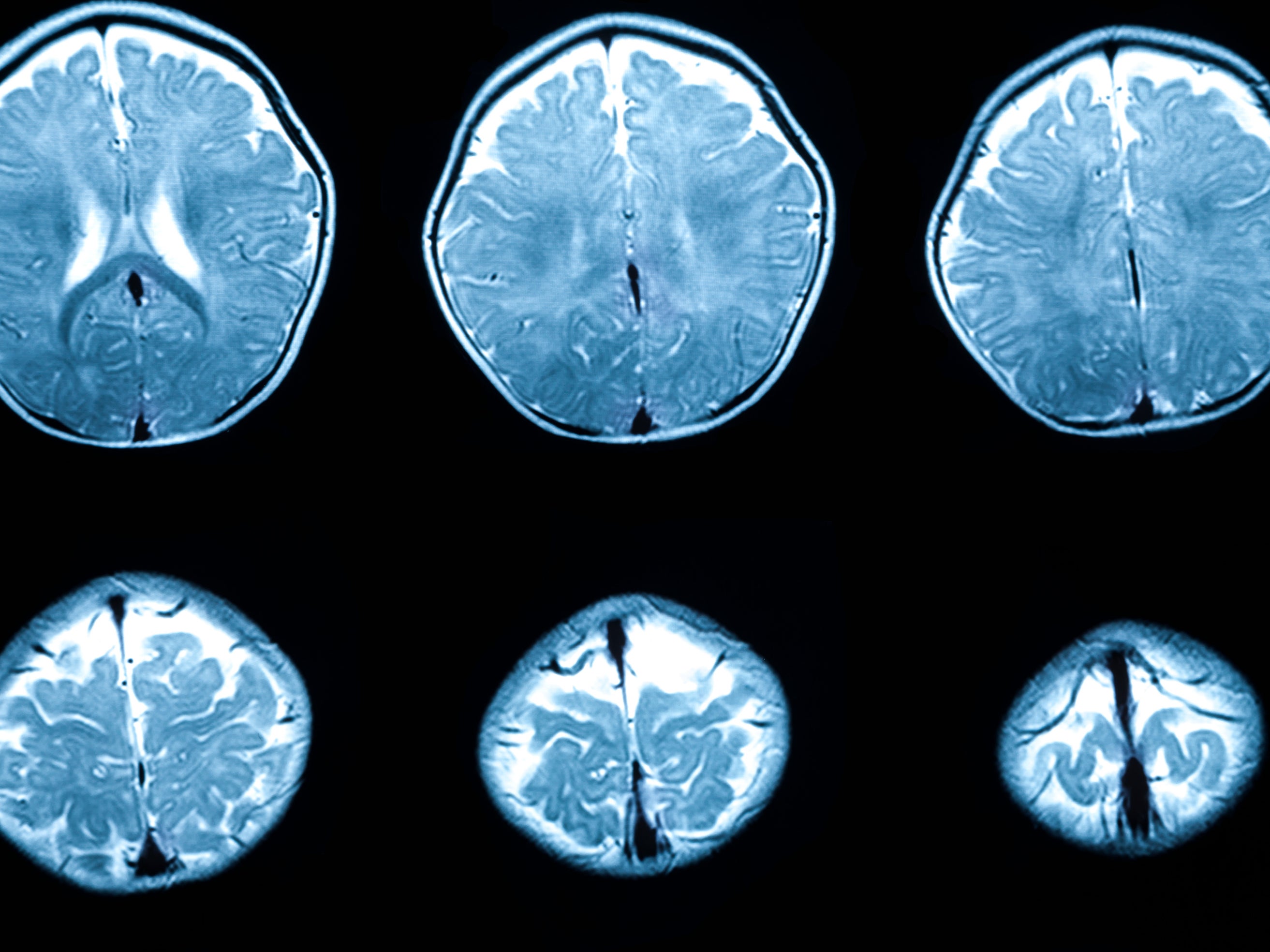

The report – published in the journal JAMA Network Open – saw US researchers conduct MRI scans on sleeping, healthy newborns all from different backgrounds.

Images showed that babies with mothers facing social disadvantages, such as poverty, tended to be born with smaller brains than babies whose mothers had higher household incomes.

Researchers found that these children had smaller volumes across the entire brain – including on the cortical grey matter, subcortical grey matter and white matter – than in the brains of babies whose mothers had higher household incomes.

The scans, which were conducted only a few days to weeks after birth, also showed evidence of brains folding less among infants born to mothers living in poverty. A healthy human brain folds as it grows and develops, providing the cerebral cortex with a larger functional surface area. Fewer and shallower folds typically signify brain immaturity.

A second study of data from the same sample of almost 400 mothers and their babies – this one published in the journal Biological Psychiatry, still by researchers at Washington University’s School of Medicine – found that pregnant mothers living in neighbourhoods with high crime rates gave birth to infants whose brains functioned differently “during their first weeks of life” than those born to mothers living in safer areas.

Using MRI scans again, the team found that babies whose mothers were exposed to crime before giving birth displayed weaker connections between brain structures that process emotions and structures that help regulate and control those emotions.

Maternal stress is believed to be one of the reasons for this weaker connection in babies’ brains, the academics noted.

“These studies demonstrate that a mother’s experiences during pregnancy can have a major impact on her infant’s brain development,” Christopher D Smyser, one of the study’s main researchers, said.

He added that research into how brain regions develop and form early functional networks is crucial “because how those structures develop and work together may have a major impact on long-term development and behaviour”.

Babies in the study were born between 2017 and 2020, before Covid-19 swept across the world and sent countries into lockdown.

In the first part of the study, involving the effects of poverty, Regina Triplett, a postdoctoral fellow in neurology and the lead author, said she had expected to find that maternal poverty could affect the babies’ developing brains. But she also expected to see effects from psychosocial stress, which include measures of adverse life experiences as well as measures of stress and depression.

“Social disadvantage affected the brain across many of its structures, but there were not significant effects that were related to psychosocial stress,” she said of the findings.

“Our concern is that as babies begin life with these smaller brain structures, their brains may not develop in as healthy a way as the brains of babies whose mothers lived in higher income households.”

In the second part of the study, however, lead author Rebecca Brady said “the stresses linked to crime” were different to finanical troubles duye to the specific effects it was having on babies’ brains.

“Instead of a brain-wide effect, living in a high-crime area during pregnancy seems to have more specific effects on the emotion-processing regions of babies’ brains,” Ms Brady, a graduate student at Washington University’s Medical Scientist Training Programme, said.

“We found that this weakening of the functional connections between emotion-processing structures in the babies’ brains was very robust when we controlled for other types of adversity, such as poverty. It appears that stresses linked to crime had more specific effects on brain function.”

The academics concluded their findings by advising governments to protect expectant mothers from crime and help them out of poverty – not just for their own safety but to improve “brain growth and connection” possibilities in their babies.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments