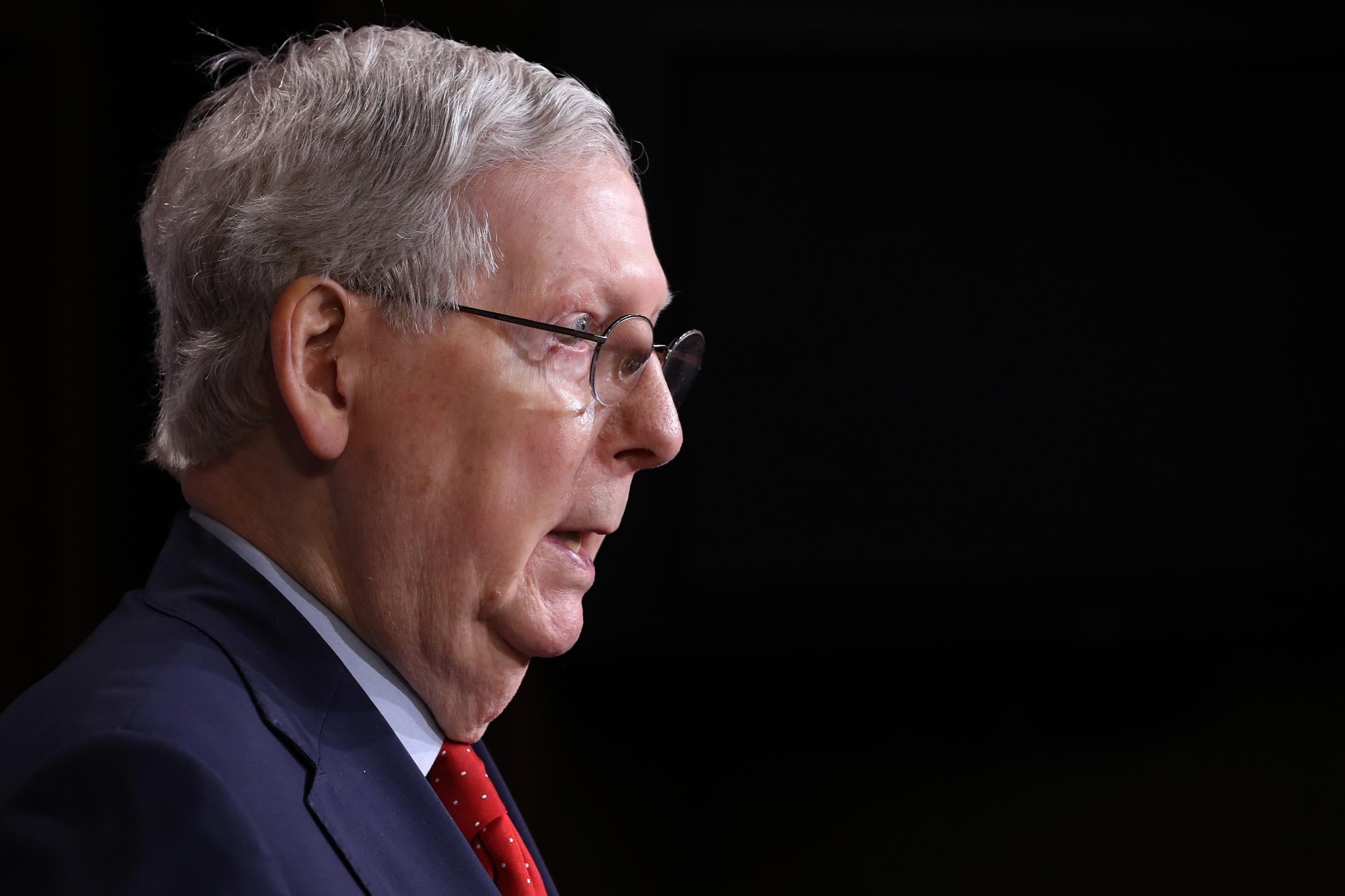

Why so many people are desperate to end Mitch McConnell’s political career

The 78-year-old faces tough challenge as he seeks 7th term, writes Andrew Buncombe

If you hang around long enough in politics, you cannot help but make enemies.

Mitch McConnell has been around an awful long time – he was first elected to the Senate in 1984 and served previously in the administration of Gerald Ford. He has an awful lot of enemies.

At the age of 78, the Senate majority leader is seeking his seventh term this November. Yet there is a wave of people determined to ensure he is not reelected, opposed not simply to his politics, but outraged by the way he has allowed Donald Trump to trample over the traditions and powers of the upper chamber of Congress.

Part of the anger is over what is perceived to be staggering hypocrisy; during the two terms of Barack Obama, McConnell was an arch-obstructionist, willing to do anything to protest over what he claimed was the president’s executive overreach. The result was very often gridlock, as with notorious refusal to call a hearing on the president’s nominee for the Supreme Court, Merrick Garland.

In contrast, he has done nothing as Trump has ripped up political norms, frequently treated the two houses and their members with disdain, and signed numerous executive orders to secure policy, something over which he used to frequently scold his predecessor.

Even worse, say some, McConnell has not just been a neutral bystander, but rather, in the words of Jane Mayer’s exhaustive recent investigation of him in the New Yorker, that he has acted as Trump’s “enabler”.

“I think the main thing is that people see the hypocrisy,” said Christina Greer, associate professor of politics at New York’s Fordham College. “They look at the way he has acted with Trump, compared to how he behaved with Obama, who did 1,000th of what the current president has done.’

She added: “People used to say, you could at least disagree with what McConnell stood for. Now it appears he does not stand for anything, other than doing what Trump wants.”

Trump’s utter takeover of the Republican Party – its policies, its people and its tone – is one of many of aspects of his presidency that will merit rich study by future historians.

Right now, six months from election day, and with Trump having rather easily survived impeachment, it is difficult to remember the last time a senior Republican stood up to him, or opposed him, or said he was wrong. The last act of genuine defiance was perhaps the cancer-stricken John McCain’s July 2017’s “no” vote to Trump’s efforts to repeal the Affordable Care Act, better known as Obamacare. He died a year later.

Since then, it is difficult to find any Republican who even seeks to hold the president to even modest scrutiny. (Mitt Romney voted to impeach Trump on one count, but not the other.)

Smoothing Trump’s path all this time has been McConnell, who to all accounts dislikes Trump intensely, but has recognised the two men require each other – Trump to ensure the party falls into line and McConnell because he recognises he needs the president’s supporters to turn out and vote for him as he seeks his seventh term as a Kentucky senator.

In bending to please the president, McConnell has done and said some remarkable things. Last week, in comments that drew derision from Republicans as well as Democrats, he opposed providing further bail-out money to individual states struck by the coronavirus and instead declare themselves bankrupt. (This was another piece of hypocrisy from McConnell, as many pointed out red-state Kentucky has long received far more in federal dollars than it ever pays in taxation.)

“Perhaps McConnell has been in Washington too long and has gotten badly out of touch — even with Republicans,” conservative columnist Jennifer Rubin wrote in the Washington Post.

Anywhere up to 10 Democrats are seeking to stop McConnell in his tracks. The frontrunner ahead of primary vote on June 23, is Amy McGrath, a 44-year former Marine fighter pilot. Her efforts have been made more challenging because of the pandemic, but campaigning has been carrying on.

Earlier this month, the Louisville Courier Journal reported that while McConnell’s campaign had raised an impressive $7.4m during the first quarter, the former marine had amassed $12.8m during the same period.

“What our numbers show is that voters are fed up with Mitch McConnell continually putting corporate handouts ahead of working people,” said campaign spokesman Terry Sebastian.

Should McConnell be worried? There have been few polls to date because McGrath first has to jump through a primary hoop, but some polling carried out in January suggested the race would be close.

Others point out McConnell may be too confident and assume his national status will see him good. His approval rating of 50 per cent is the second lowest of any senator, and commentators point out that “all politics is local”.

A number of high profile national incumbents – Republican House majority leader Eric Cantor and Democratic House chairman Joseph Crowley – both lost to long-shot challengers while their backs were turned.

In June 2014, Cantor lost in a primary challenge by economics professor Dave Brat, while Crowley lost the 2018 Democratic primary for his New York congressional seat to a certain Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

On Tuesday, former Republican congressman Joe Scarborough, now a popular morning news anchor, said McConnell was committing “political suicide” by continuing to cover Trump during the pandemic.

“Mitch McConnell is not just concerned about not being majority leader, Mitch McConnell may not win re-election,” Scarborough said on MSNBC. “Mitch McConnell is carrying water for a president who was telling people to inject disinfectants into their body.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments