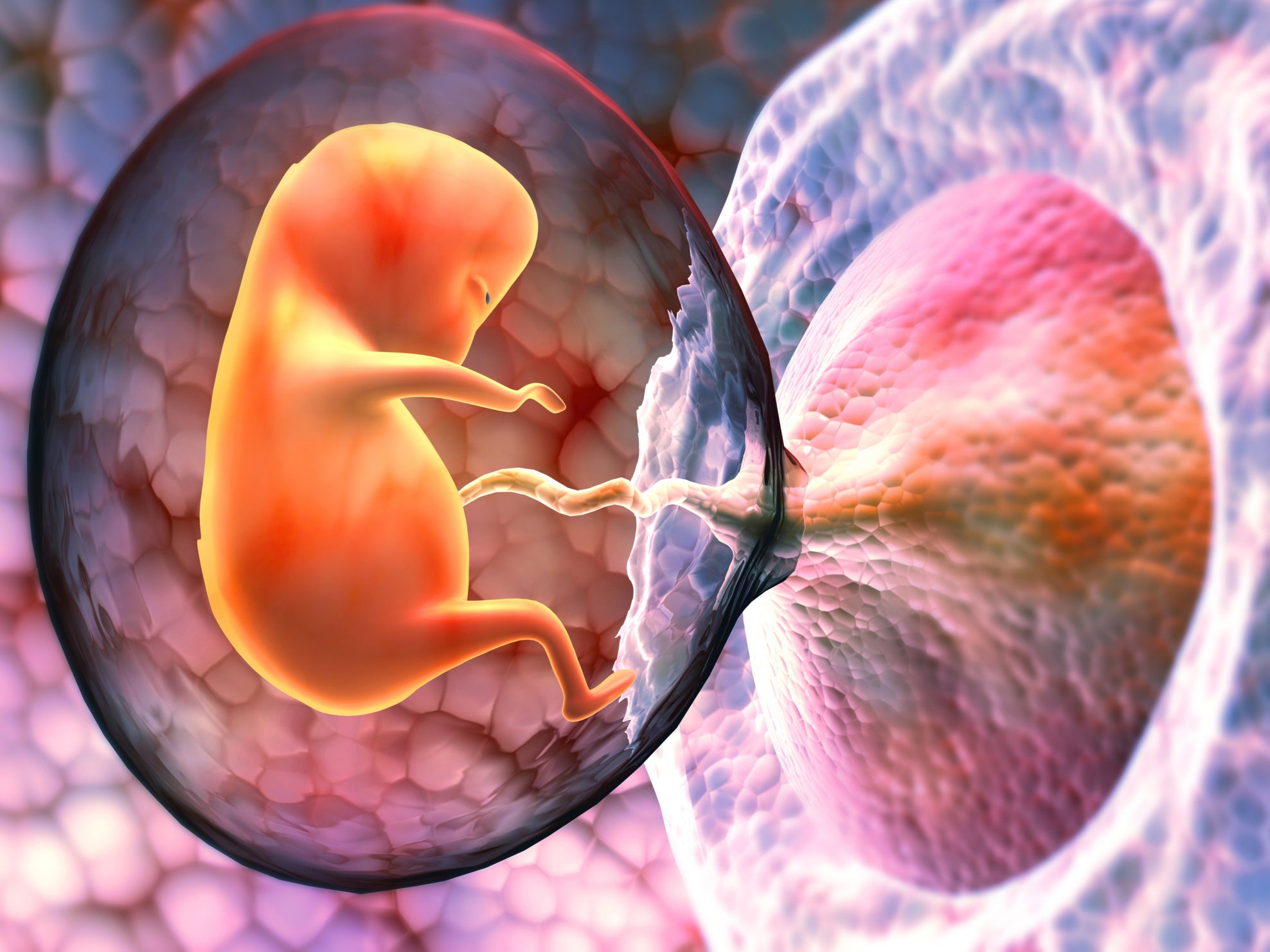

Genes fight it out for resources in battle of the sexes in womb, study finds

‘There’s a tug of war taking place at the level of the genome’

Genes inherited from the mother and father in the womb fight it out for resources in a “battle of the sexes”, according to new research.

In a study by Cambridge University, scientists found that as a foetus grows in size and indicates its need for nutrients from its mother, this signal encourages the growth of blood cells in the placenta which involves a “tug of war” between genes inherited from the parents.

The study – involving genetically engineered embryonic mice – found the signal, known as IGF2, causes the paternal and maternal genes to counterbalance the additional demands for food and nutrients.

Lead author, Dr Miguel Constancia, said: “One theory about imprinted genes is that paternally expressed genes are greedy and selfish. They want to extract the most resources as possible from the mother.

“But maternally expressed genes act as countermeasures to balance these demands.

“In our study, the father’s gene drives the foetus’s demands for larger blood vessels and more nutrients, while the mother’s gene in the placenta tries to control how much nourishment she provides.

“There’s a tug of war taking place, a battle of the sexes at the level of the genome.”

Dr Ionel Sandovici, the paper’s first author, said: “As it grows in the womb, the foetus needs food from its mum, and healthy blood vessels in the placenta are essential to help it get the correct amount of nutrients it needs.

“We’ve identified one way that the foetus uses to communicate with the placenta to prompt the correct expansion of these blood vessels.

“When this communication breaks down, the blood vessels don’t develop properly and the baby will struggle to get all the food it needs.”

The scientists found that IGF2 reaches the placenta through the umbilical cord, with levels of the signal progressively increasing from 29 weeks to full term.

Too much IGF2 means there will be excessive growth while too little is associated with poor growth – both are linked to health complications.

The study may help improve understanding of how the foetus, placenta and mother all communicate during pregnancy and can lead to new ways of using medication to normalise IGF2 levels.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments