From a landslide to a pandemic: Boris Johnson’s premiership one year on from his victory at the polls

Sean O'Grady looks back at a whirlwind 12 months for the prime minister

As John Lennon asks us still at Christmas, “another year over, and what have you done?” In the year since his undeniably impressive general election win, Boris Johnson has done a great deal (though not yet literally in those tricky EU trade talks), has had plenty done to him and, to his credit, managed to survive a near death experience – joking aside, which is never easy for him. Even if he’s pushed out next year, he’s amassed sufficient material already for an entertaining rip-roaring memoir and a lifetime supply of yarns to fill lazy newspaper columns (thence recycled into relaxed after dinner speeches). Lennon, working class hero, might not have been so impressed, though, and you get the idea that his colleagues and the voters are starting to wonder about the choice they made.

DECEMBER 2019

Obviously free of superstition, on 13 Friday December Her Majesty the Queen invited Boris Johnson to form a government. Whether she might have had her own doubts about this we may never know, but she was constitutionally obliged to “send” for Johnson as he had just won a stonking majority in the general election. He’d vanquished Jeremy Corbyn, humiliated Jo Swinson (the now forgotten figure who’d granted him his early election), crushed Nigel Farage and emerged with a working Commons majority of about 87. It was the largest won by the Tories since 1987, and the best vote share since 1979. A blonde colossus bestrode Westminster: a frightening if awesome figure.

Like many of her subjects, the Queen was probably relieved, though, that at least the country had a functioning majority government, even if it was led by a charlatan who had not long since advised to prorogue parliament illegally. The days of broken promises, perpetual crises, and bewildering parliamentary dramas were over, weren’t they? No more chaos and U-turns, eh? The days of embarrassing leaks and never ending talks with the EU just bad memories, what? At last Brexit was about to “get done”, wasn’t it? After all, it was during that very election campaign that Johnson was interviewed by a BBC local radio station and was asked about the risks of breaking with the EU at the end of 2020 without a trade deal he said: “I think they are absolute zero”. What could be more confidence inspiring?

Around the time Johnson making some minor adjustments to his cabinet, reports started to come through from China that a mysterious new virus had claimed its first casualty from pneumonia.

JANUARY

In his New Year’s message the prime minister declared: “That distinctive sound you may have heard at midnight as the bongs of Big Ben faded away was not the the popping of champagne corks or the crackle of fireworks from your neighbour’s garden.

"Rather it was the starting gun being fired on what promises to be a fantastic year and a remarkable decade for our United Kingdom.”

That distinctive sound you may have heard at midnight as the bongs of Big Ben faded away was not the the popping of champagne corks or the crackle of fireworks from your neighbour’s garden. Rather it was the starting gun being fired on what promises to be a fantastic year and a remarkable decade for our United Kingdom

An unfortunate set of predictions there, and proof of what his old colleague George Osborne was later to call the prime minister’s “optimism bias” which was to operate surprisingly undimmed as the nation’s woes piled ever higher. To be fair, the UK-EU withdrawal bill was finally passed by parliament and ratified by the EU. The UK formally left the EU on 31 January at 11pm (midnight, Brussels time). Because of unavoidable repairs Big Ben was out of action, and an image was instead projected onto Downing Street, with pre-recorded bongs. Nigel Farage led a patriotic singalong in Parliament Square. There was an “event” organised by a Tory MP. It was no VE Day, but muted and sad for many. He kept a low profile, but Britain, said Johnson, was about to “unleash its full potential”. Critics countered that Brexit was “far from done”. A week before Johnson’s health secretary breezed out of a Cobra meeting to brief the press that the risk to the public from coronavirus was “low”.

FEBRUARY

The prime minister might be forgiven for taking the opportunity to go into full rooster booster mode, surrounded as he was by the grandeur of the Old Naval College at Greenwich, but at times he got carried away in his first post-Brexit-sort-of keynote speech. The claim that “we have ended the debate that has run for three and a half years” was far-fetched. The “great voyage” that buccaneering global Britain was about to embark would upon, for example, compares rather badly with the ferry jams likely to materialise by the year end. So would his throwaway remark about the growing evidence of the threat of the coronavirus: “When there is a risk that new diseases, such as coronavirus, will trigger a panic and a desire for market segregation that go beyond what is medically rational to the point of doing real and unnecessary economic damage”. Mysterious, in the circumstances of the mounting public health crisis, was the prime minister skipping five Cobra meetings, disappearing from public view for 12 days, including a week-long break at an official “grace and favour” mansion, Chevening. Johnson’s absence was variously attributed to him honouring a book contract, finalising his divorce from second wife Marina Wheeler and putting the finishing touches to the announcement of his engagement to his pregnant partner Carrie Symonds (on 29 February).

At any rate, these were vital days going into March when, according to some, opportunities were missed to stem the spread of the virus and secure supplies of protective equipment. Arguments at the top of government about herd immunity raged without much input from the premier, who seems to have left things to the scientists, plus health secretary Matt Hancock and chief adviser Dominic Cummings. As a result vital days were wasted and lives lost: one Downing Street colleague offered this harsh judgement: “There’s no way you’re at war if your PM isn’t there. And what you learn about Boris was he didn’t chair any meetings. He liked his country breaks. He didn’t work weekends. It was like working for an old fashioned chief executive in a local authority 20 years ago. There was a real sense that he didn’t do urgent crisis planning. It was exactly like people feared it would be.”

What Johnson did find time for was a reshuffle in which he ditched nonentities such as Andrea Leadsom and Theresa Villiers, the last of the useful Eurosceptic idiots he had happily exploited. In their place he promoted new nonentities such as George Eustice and Suella Braverman, who did nothing to energise an intellectually underpowered and inexperienced top team.

Worse still was an ill-judged attempt to take over the Treasury, seemingly at the behest of Cummings, who demanded control over all of Whitehall’s disparate squad of special advisers. When the chancellor, Sajid Javid, put up some determined resistance to losing his power to choose his own advice, and thus diminish the power of the Treasury he had to resign. In his place Johnson appointed the chief secretary to the Treasury. A young comparatively junior figure, Sunak’s appearances in the election campaign has been linked to those of a children’s television presenter. To borrow an old political insult, however, Sunak was soon to rise from “boy wonder to elder statesman without any intervening perks whatsoever”. In the ensuing crises, the supposed puppet was to be Johnson’s greatest rival, his boss fearing he might quit over no deal Brexit. And HM Treasury saw off yet another challenge to its authority. The episode did not impress Johnson’s MPs. The PM proposed building a bridge between Scotland and Northern Ireland, and reviving the “Boris Island” airport in the Thames Estuary, after the third runway at Heathrow was ditched (a rare Johnson promise kept).

MARCH

A busy and difficulty month, with allegorical qualities. It started with a bright prime minister doing his boosterish shtick on a hospital visit and ended with a positive test for Covid-19 and a sweaty, breathless video of the prime minister claiming to be fine when he patently was not. At a press conference on 3 March he showed little understanding of “the science” supposedly guiding his every step: “I was at a hospital the other night where I think there were actually a few coronavirus patients and I shook hands with everybody ... We should all basically just go about our normal daily lives ... The best thing you can do is wash your hands with soap and hot water while singing ‘Happy Birthday’ twice.”

I think, looking at it all, that we can turn the tide within the next 12 weeks and I’m absolutely confident that we can send coronavirus packing in this country

Two days later came the first recorded death in a British hospital from Covid. The much-derided experts were projecting between 250,000 and 500,000 deaths, and a broken health system, if nothing was done. On the 17th the virus had reached all parts of the UK. On 23 March, after a false start and much dither and delay, Johnson moved from requesting voluntary action and announced that soap and water and avoiding the pub were no longer enough: evidenced when his dad, Stanley, declared he’d go to the pub if he “needed to”.

Given such paternal defiance, Johnson had no choice but to impose the greatest curbs on civil liberties and economic activity ever to a mostly petrified public. Johnson was pleased to have “the two gentlemen of Corona”, chief medical officer Chris Whitty and chief scientific adviser Sir Patrick Vallance as has wing men in the daily press conference defences, adding knowledge and sober authority.

Brexit hardly figured in the news, and when Michel Barnier, for the EU, warned again that there were “grave differences” between the two sides he was as truthful and prescient as he was ignored.

APRIL

Was the worst day of Johnson’s premiership when he was taken to St Thomas hospital with “persistent symptoms” of Covid, or the day before when, virtually unnoticed, Keir Starmer took over as leader of the Labour Party?

The first was certainly the more shocking, and there was a genuine sense of public sympathy for him and the pregnant Carrie, who had also caught the disease. Apart from some haters on social media, the nation wished him well. Yet even in this extreme circumstance Johnson had refused to appoint anyone to formally discharge duties such as chairing cabinet, and Johnson, intentionally or not, left behind a vacuum in which senior ministers such as Dominic Raab or Michael Gove seemed reluctant to take executive decisions. It was all a bit reminiscent of Armando Iannucci’s film The Death of Stalin, in which fear and mutual mistrust among the old monster’s succession rivals paralyses them from action. Thankfully, though, and unlike Stalin, Johnson recovered. A few days later he gave an uncharacteristically weepy interview to The Sun: “The bad moment came when it was 50-50 whether they were going to have to put a tube down my windpipe.” According to The Sun’s account, the prime minister “welled up as he relived the extraordinary two weeks in which he nearly lost his own life but recovered in time to see the birth of another, his new son Wilfred. Johnson’s “eyes redden and he pauses to take a deep breath” then went on: “I get emotional about it ... but it was an emotional thing.” Wilfred was given the middle name Nicholas, after the two doctors who looked after the premier – Nicholas Price and Nicholas Hart. Johnson’s time in intensive care seems genuinely to have chastened him. His main nurses, one from New Zealand and the other from Portugal, briefly became national celebrities.

Less happily, some say Johnson lost some of his bounce and power of concentration after the illness. The most uncharitable version emanated from Dominic Cummings’s father-in-law who predicted Johnson would step down by next spring, likening Covid to an equine fetlock injury: “If you put a horse back to work when it’s injured it will never recover”. Knackered, in other words. On 30 April he declared the nation was past the peak of the disease – but hardly for his own troubles.

MAY

If Covid drained Johnson of physical vitality, defending his adviser Dominic Cummings drained him of political vitality. The revelations in the media about the trip to Durham, the hypocrisy and the absurdities of using a 30-mile drive as a test for eyesight enraged the public, the opposition, but also Tory MPs.

The “Dominic Cummings Effect” was twofold. It eroded willingness to comply with any Covid restrictions, and it hammered Johnson’s personal approval ratings, dropping by 20 percentage points, dragging his party and government down with it, and leaving Starmer ahead on leadership. Johnson’s statement that Cummings had “acted responsibly, legally and with integrity” was believed by almost no one, possibly including Johnson himself. One of the stars of the crisis, deputy chief medical officer Jonathan Van-Tam couldn’t conceal his irritation, and others had to be asked to keep shtum.

The curiosity was why Johnson expended so much political capital on Cummings. It was suggested he was Boris’s indispensable “brain”, that he had a Svengali-like hold over him or that he knew too much about the premier’s private life to be let loose; but the effort did Johnson’s waning fortunes no good. In terms of his judgement and consistency of purpose, it made it all the stranger when Cummings and his allies were dismissed only months later. Two notable U-turns rounded off a tough month: junior NHS staff from abroad would no longer have to pay a fee of £400 to use the very hospitals they worked in. A “road map” out of Covid lockdown was published only to be abandoned before long, just like the coronavirus action plan before it and various other half-forgotten strategies after.

JUNE

The Department for International Development was scrapped, which was bad news for the world’s poor but politically astute in that the opinion polls consistently showed hostility to aid, even before the Covid crisis. Promises made in the December manifesto that the aid budget would be protected were reiterated before being ditched in November.

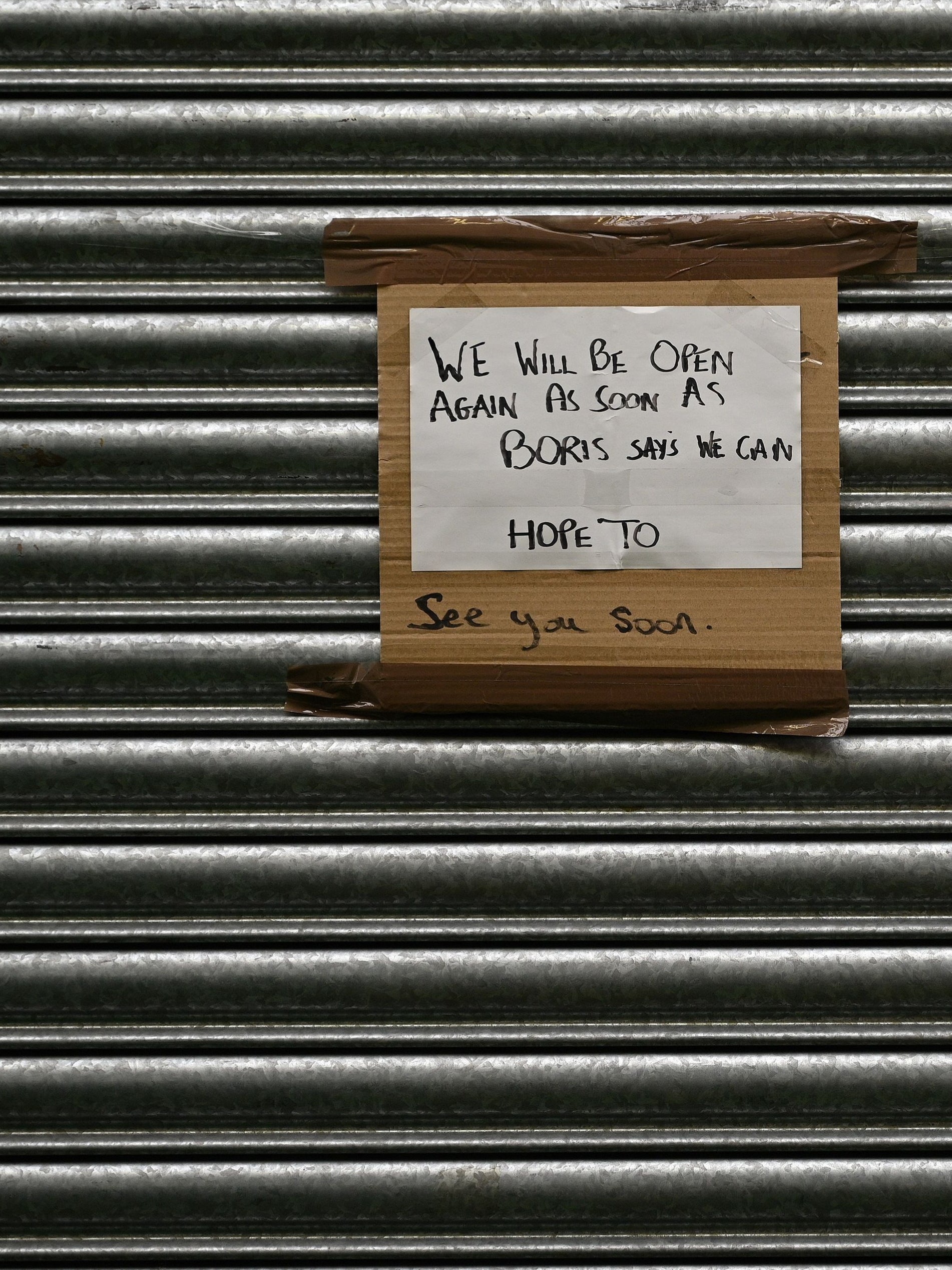

Things were going better in Covid, though, and there are relaxations at home for shops and the “bubble” is introduced. Yet again, though, the prime minister over-promised, ending the daily press conferences as if that would perversely itself make the virus disappear: “We are winding down the rhythm of these press conferences ... basically because we’re continuing to make good progress in controlling the virus and we want to make sure we have something really important to say.” The downside was a loss of clarity in messaging and that Nicola Sturgeon carried on with hers, adding to the impression that she was taking things more seriously than her counterpart.

Nor was she alone. A viral campaign by footballer Marcus Rashford on free school means forced another U-turn. The test and trace app was postponed, to no one's surprise. The Black Lives Matter protests and the dethroning of statues to slave owners offered Johnson to move back to fighting the culture war, which he has more chance of winning than the one against Covid.

JULY

Easier, happier times, if only temporarily. The long-delayed report into Russian interference in the 2016 Brexit referendum and general elections was published having sat on the prime minister’s desk for months. It concluded that the government hadn’t bothered to find out whether there had been any such activity, oddly, and thus it was difficult to assess. Johnson simply didn’t want to know what Putin’s proxies had been up to. You wonder why.

AUGUST

“Sh*tshow” was the blunt verdict of a government insider on the governance of Britain. The A-level results, now awarded on coursework alone, were a mess and wrecked university admissions. After a period of silence, Johnson pronounced: ”Let’s be in no doubt about it, the exam results that we’ve got today are robust. They’re good, they’re dependable for employers.” They weren’t, After four days they had to be revised. A lesser focus for confusion was the great masks in school debate, the subject of yet another U-turn. The prime minister was getting more mixed up through the year about his own rules, though this didn’t draw him to the obvious conclusion. Having seen Covid restrictions been greatly relaxed, there were signs of infections creeping up, partly through that lack of clarity and consistency. A row about “Rule, Britannia!” and the Proms availed the prime minister an opportunity to tell the BBC to stop being “wet”, just like he used to say at Eton and to David Cameron. Michel Barnier warned that the Brexit talks were going nowhere.

SEPTEMBER

The exam results that we’ve got today are robust. They’re good, they’re dependable for employers

The ban on residential evictions was reinstated before it was lifted, a sort of new fangled post-Brexit British innovation in U-turns, the production of which has been one of the few areas of expansion in the economy.

The announcement that the prime minister was willing to break the UK-EU withdrawal agreement provoked a furious reaction from the EU.

OCTOBER

The prime minister, at his most portentous, and with weary resignation declares that the EU talks should be ended on 15 October, and abandoned if there is no sign of accord. Not for the first or last time, the iron deadline proves to be rather rubbery.

After another round of dithering the PM agrees on 14 October to a system of regional tiered lockdowns rather than having to impose a national lockdown. He ridicules Starmer for wanting to “close the whole economy down again”, at vast cost. On 31 October, Halloween, he announces a national lockdown. A certain insensitivity to the north angers Andy Burnham, other mayors and MPs of all parties.

NOVEMBER

On Friday 13 November, funnily enough, Downing Street lets it be known that Dominic Cummings is to leave his job after all. Briefings and counter-briefings suggest that the broadly dysfunctional Downing Street set up established in the bright confident dawn of the Johnson era in July 2019 had, like a Soviet nuclear power station, finally burned its own core reactor. Cummings left by the front door in what looked to be a stage managed photo opportunity, and the images of the Mekon with his dreams and plans in a cardboard storage box shambling into the darkness was indeed striking and symbolic.

What also became apparent was just how influential the prime minister’s fiancee has been. Rather than smashing the machinery of government or mismanaging the pandemic or shredding confidence in the Covid rules or terrorising junior staff, Cummings’s crime was to refer to the chatelaine of Downing Street as “Princess Nut Nut”, which is a bit ironic coming from old light-bulb head himself. The prime minister has seemingly scrapped Cummings’s scheme to turn the sleepy Cabinet Office into Nasa, and got himself a competent conventional chief of staff. It may be too late.

Meanwhile the official UK death toll reached 50,000, on Remembrance Day. Sombre though he was, the prime minister yet again overplayed his hand: “Every death is a tragedy but I do think now we got now to a different place in the way that we treat it”. It’s true that the therapeutic drugs are better, and death less likely, but the infections remain stubbornly high.

Having declared devolution a “disaster” the SNP offer thanks and prayers to the prime minister for his past and future services to Scottish independence. He may think of her as “that bloody Wee Jimmy Krankie woman” but she surely cherishes him as a political asset.

On the Covid restrictions, and with plenty of other grievances, Johnson suffered the worst Commons rebellion of the year; not the loyal vote of confidence he needs from his fractious, factional ill-tempered party.

DECEMBER

The first day of the new month saw Priti Patel sort of confirmed of being a sort of bully by an official enquiry and giving a sort of apology. Like all good not-bullies she required the protection of someone bigger than her so Johnson told his MPs to “form a square around the Pritster”, which does sound like something from his schooldays. The dinner date from hell with Ursula von der Leyen went as badly as you’d expect, and she proved impervious to the famous Johnson charm. No matter; Britain will prosper mightily anyway.

As if to revive past glories Boris Johnson referred to his administration as “the people’s government” for the first time in yonks at prime minister's questions, reminding himself, his ambitious colleagues and Labour that it was him – Boris, Bozzer, BoJo – who stole the “red wall” seats a year ago.

One note to celebrate is the arrival of the vaccine. There is still time for the logistics to be fouled up, like the world-beating “moon shot” Covid test and trace system that never quite turned up as described; but if things go better in 2021 than in 2020 then he might still be in his current job by next Christmastide. Another year over...

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

510Comments