In the Aegean Sea, a dangerous dance between Turks, Greeks and desperate migrants

Migrants making the dangerous crossing across the Aegean sea are finding themselves caught up in tensions between Greece and Turkey, writes Borzou Daragahi

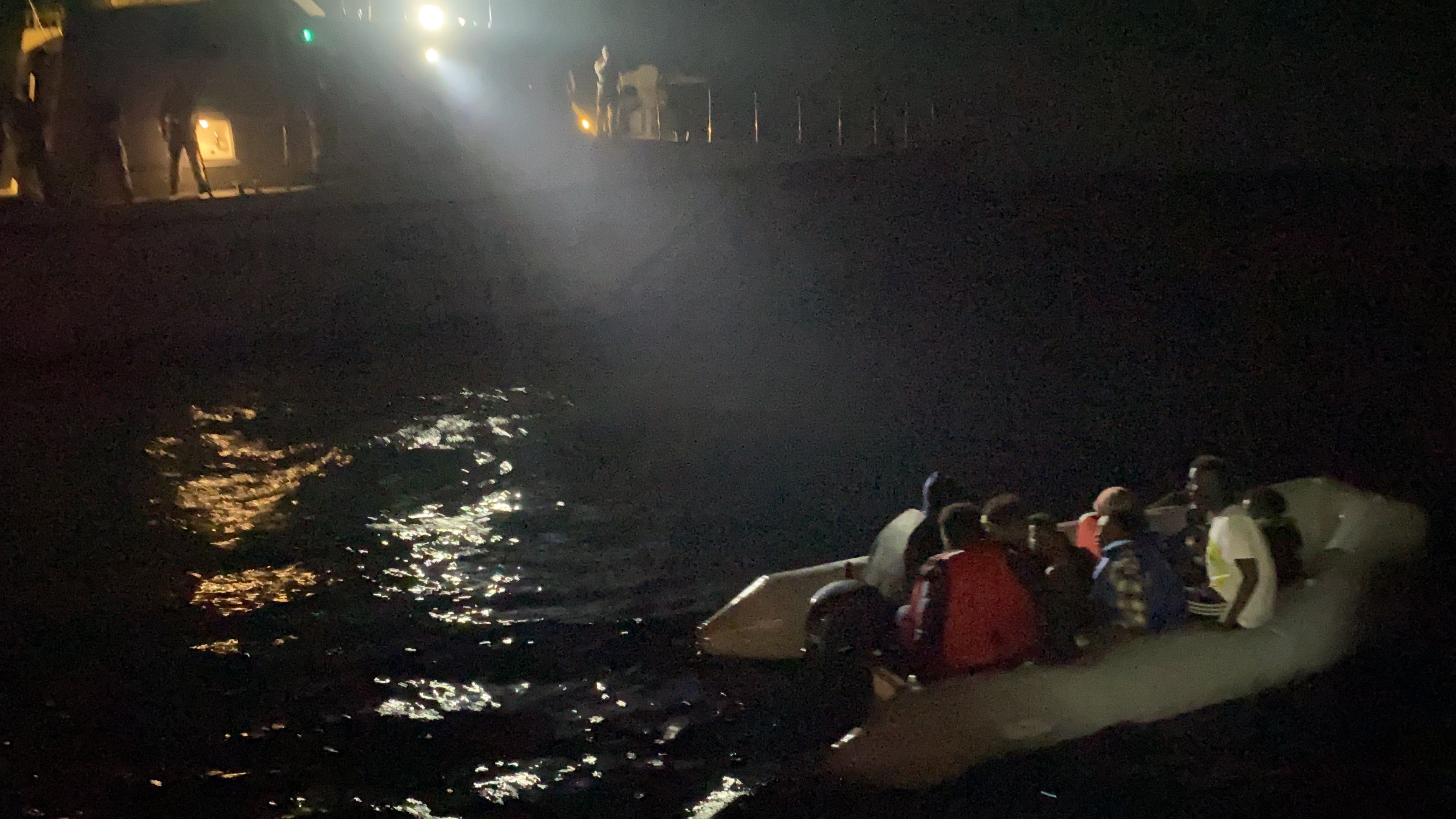

The tiny boat finally appears beneath the moonlight, bobbling precariously in the ink-black sea. Its passengers had set out from the Turkish Aegean coast for the Greek Island of Lesbos, among the hundreds of thousands of migrants from all over Asia and Africa who gather in Turkey in hopes of making it to Europe.

But a short while into their journey, they ran into some kind of trouble. One passenger used a mobile phone to call an international emergency number. The passengers’ pleas for help reached the Turkish coastguard, initiating a rescue mission that in recent years has become an all-too-frequent and dangerous ritual on the choppy seas.

Sometimes the rafts full of migrants encounter engine trouble. But all too often, they are put in danger as a result of deliberate sabotage, often by smugglers attempting to use one faulty boat to draw authorities away from others. They are menaced by Greek coast guard vessels damaging boats and directing them back toward the Turkish coast.

“It can be a pushback or a mechanical problem,” says Major Sadun Ozdemir, commander of the North Aegean Group of the Turkish Coast Guard, as the rescue mission gets underway. “It doesn’t matter right now.”

Passages across the Aegean have been going on for years, especially along this particular stretch of coast dotted with scores of possible launch points. Turkish authorities have sought to highlight Greece’s pushbacks of migrants, criticised by human rights groups and even the European Union as cruel and possibly a violation of international law, as a way of shining an unflattering light on a longtime rival.

Instead, a rescue mission with the coastguard shows a perilous and confusing three-way dance between Greeks, Turks and migrants at sea, interacting in close quarters in the dead of night.

It is well into the hours of the morning when the coastguard ship, along with a small group of international journalists including The Independent, leaves port from Turkey’s Cunda Island for the distressed boat. It is a full moon, and the sea glimmers beneath a crystal clear night.

The Kaan-19 class coastguard ship sails smoothly out of the harbour, and then roars its two 1,500 horsepower engines to near full throttle as it heads out to Candarli Bay, just west of Tavsaa or Rabbit Island.

The sea is calm, and the night crisp and cool – the ideal season to attempt a crossing. This time of year, the Turkish coastguard conducts at least five or six rescues a week.

Major Ozdemir explains that another coastguard ship arrived earlier, and was keeping an eye on the boat, but that the rescue wouldn’t commence until the boat with the journalists arrived.

As the ship nears the approximate location of the migrants, a Greek coastguard vessel emerges from the darkness, just a few hundred metres away, apparently in Greek territorial waters. Suddenly, a blinding flood of light strikes the Kaan-19. The Greek boat has shone its floodlights on the Turkish ship, seemingly menacing it.

Ozdemir says he finds such behaviour outrageous, a violation of the seafarers’ code of conduct and a perversion of what it means to be a member of any coastguard. “They aren’t there for rescue or helping; they’re there to prevent the migrants,” he says.

It is a dangerous game. Though the two Nato partners interact at a command level, there is no direct communication between ships at sea. If Turks detect a ship stuck on the Greek side of the waters, perhaps they will call their counterparts on channel 16, the one dedicated to communications about irregular migration.

The chance of an accident or collision between the two coastguards appears high. A 2018 collision between Greek and Turkey naval vessels became an international incident, ultimately settled by the two countries’ foreign ministers.

In April, Turkey was accused of attempting to ram two European patrol boats taking part in a border control operation. “In both cases, collision was narrowly avoided at the last minute,” Costas Mavrides, a Greek Cypriot member of the European parliament, wrote.

Just last month, Greek authorities claimed a Turkish Coast Guard vessel just east of Lesbos caused minor damage to one of its ships.

But Greece has also come under fire for reckless behaviour. It has been accused of repeatedly taking migrants who’ve crossed into its territorial waters, putting them on rafts, tugging out to sea and cutting them loose, to either die or be rescued by Turkish coastguard.

In some cases, Greece has even allegedly sent back migrants who have reached land.

“I am particularly concerned about an increase in reported instances in which migrants who have reached the Eastern Aegean islands from Turkey by boat, and have sometimes even been registered as asylum seekers, have been embarked on life-rafts by Greek officers and pushed back to Turkish waters,” Dunja Mijatovic, the Council of Europe’s commissioner for human rights, wrote in a letter addressed to Athens authorities in May.

Athens has insisted that Turkey facilitates the flow of migrants, and has accused the Turkish Coast Guard of guiding the boats into Greek waters, a claim vehemently denied by Ankara.

Major Ozdemir says about 70 per cent of the migrant boats they encounter are those turned back by Greece. The Turkish Coast Guard says it has rescued at least 6,956 in the first six months of 2021, compared to 11,728 during the same period last year, but expects the numbers to jump during the summer months as the easing of coronavirus restrictions unleashes travel.

Even locating the migrant ships is a challenge. The Kaan-19 class ship is equipped with the latest in surveillance and detection technologies, but they’re useless for spotting the dinghies used by migrants until they are close.

“It’s impossible to detect it from a point more than a mile away,” Major Ozdemir says. “If there’s a passage five miles to the north or south of you it won’t show up on a radar.”

In order to detect all the passages along the porous coast, a boat would have to be positioned every two nautical miles, he says.

The distressed boat full of migrants finally appears, first a dot in the distance and growing ever larger. The Kaan-19 slows down. The rescuers put on surgical gowns as Covid-19 prevention measures. Now comes the most dangerous part.

Waves roil even relatively still waters. The 22.5m, 30-ton Kaan-19 could easily strike and capsize the flimsy rubber dingy it approaches. The coastguard throws the migrants a rope and tells the passengers to hang onto it.

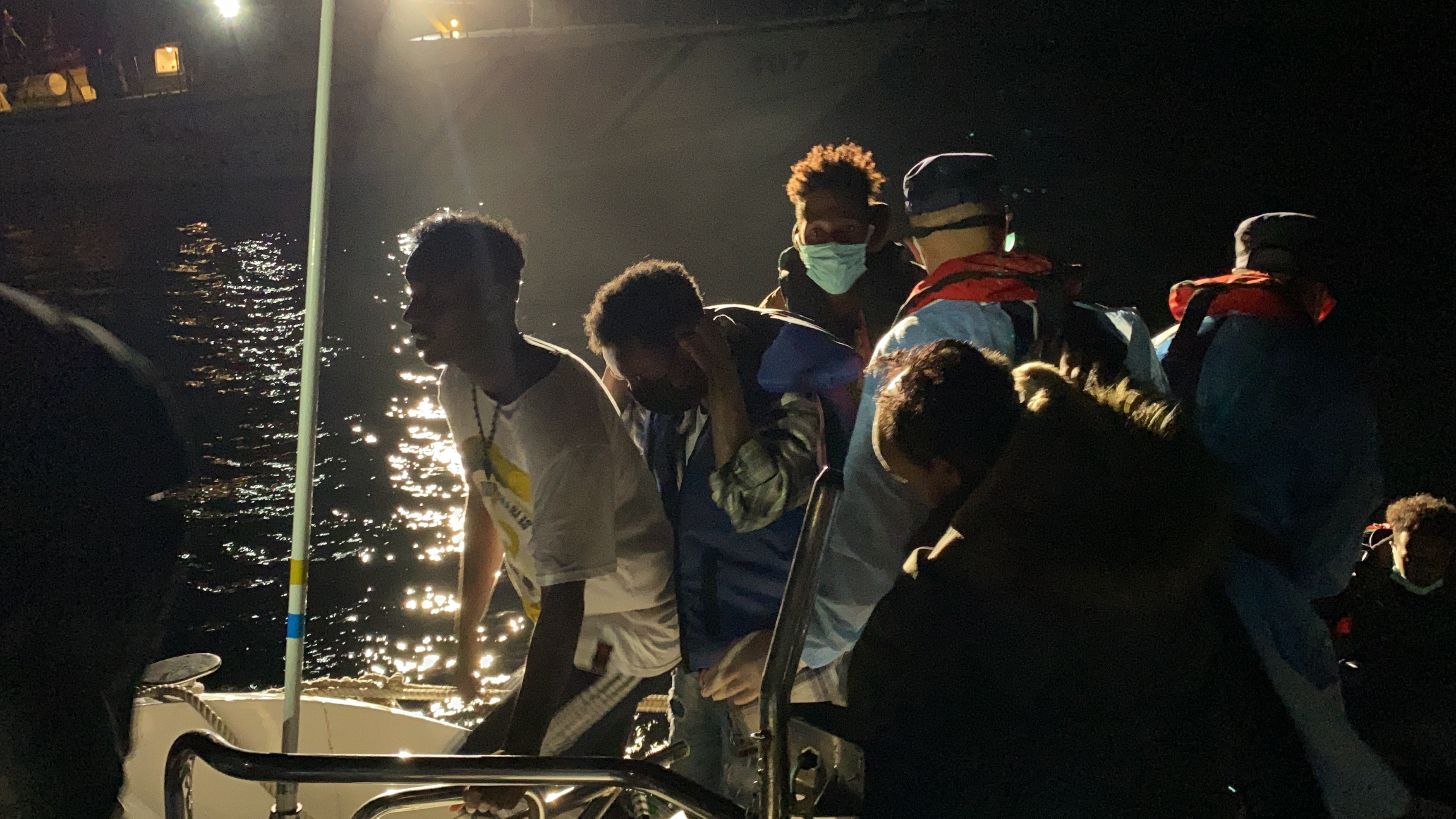

As the migrant raft is drawn to the Kaan-19, panic ensues as the migrants struggle to get aboard. “One by one,” says an officer, but no one is quite sure where they are from or what language they speak.

They struggle to get aboard, climbing up the ladder, and making their way onto the deck of the Kaan-19.

They are all from Somalia, nine men, and a woman named Adouma who appears to be in the later stage of pregnancy. Mohammed Ahmad Hassan explains in broken Arabic that he had flown to Turkey from Mogadishu two years earlier, lived in the Ankara area for two years, and tried to save up money to pay the smugglers to get him to Europe. Another passenger said he had spent a year picking apples before gambling his savings on the voyage

They had boarded the boat on a desolate beach and departed into the unknown after receiving some basic sailing tips from the smugglers they had each paid $250.

“Someone took us here, and gave us the boat, and told us to go,” says Youssef, one of the migrants.

The trip was going smoothly, but at one point, the engine had stopped, and the inflatable raft had begun taking water.

“We were in the boat three hours when the engine caught fire,” Hassan says. “It was losing air.”

Back on land, the migrants are taken to an interior ministry processing facility. They are given clean clothes, water and something to eat.

Many of them have thrown out their identification papers, so as to make it more complicated to deport them back to their own countries. Major Ozdemir says each migrant is subject to biometric identification measures. In 2020, Turkey caught 454,000 irregular migrants, whether on sea or land, along its various borders.

The sole interpreter from the International Organisation of Migration speaks Dari or Persian, making it difficult to communicate with them. But through the haze of languages and dialects, someone tells the migrants that he is happy that they are now safe.

One of the migrants, speaking English, replies, “I am happy you’re saving us.”

Burhan Yuksekkas contributed to this report

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments