Sister Norma and the ‘Cowboy Priest’ on the frontline of mercy

To Trump supporters they are worse than a menace, writes Andrew Buncombe from McAllen, but for the migrants of Central America they are heroes

Every superhero needs a catchy name. So people call Father Roy Snipes the “Cowboy Priest”. Norma Pimentel doesn’t have a fancy moniker but she has been referred to as the “Pope’s favourite nun”. And along the Rio Grande Valley and beyond, people know her simply as “Sister Norma”.

Are they heroes? To Donald Trump and his supporters, seeking to build a wall on the border with Mexico and to keep out would-be migrants and asylum seekers, they are anything but. Yet, to the countless poor and aspirational people from Central America, hungering for a better life for their children, and to whom they have given aid, sustenance and dignity, they surely are.

“Sister Pimentel has been on the frontlines of mercy for three decades,” Texas politician Julián Castro, who served in Barack Obama’s cabinet, wrote last year, when Time magazine included her in a list of its 100 most influential people.

Read more:

“Her work has taken on greater importance in the era of Donald Trump, and for good reason. While he has acted with cruelty toward migrants, she has acted with compassion. While he has preyed on the vulnerable and sought rejection, she has preached community and acceptance. And while he has promoted fear, she has taught love.”

As Trump sought to use executive orders to fund and push his wall, helped by a group of supporters, including Steve Bannon, Sister Norma and the Cowboy Priest spoke out against it. She attended a State of the Union address, and a roundtable discussion when the president visited Texas. She urged him to drop what was known as the the Remain in Mexico policy, or Migration Protection Protocols (MPP), that required asylum-seekers to live in dangerous cities south of the border while their claims were assessed.

“I realise your attention is needed in multiple areas, Mr President. However, I invite you to take a closer look at what is happening along the border due to the MPP,” she wrote in an op-ed in the Washington Post. “If you visit my community in Brownsville, the first thing you will see as you cross the Rio Grande into Matamoros, Mexico, is what has become a “tent city” along the riverbank. Some 2,500 people, many of them women and children waiting in harsh open air, are finding shelter in donated tents.”

Snipes, meanwhile, highlighted efforts to build a section of the wall on land containing a wildlife sanctuary and a 155-year-old chapel, which is supposedly protected by Congress and an international treaty with Mexico. “This is a sacred place. This should be respected and honoured,” he told a reporter. For doing so, Snipes was denounced by military veteran Brian Kolfage, a staunch conservative and friend of Bannon, who headed a non-profit group called We Build the Wall, which raised money to buy private land on which to build a wall. With no evidence, Kolfage accused the priest of “promoting human trafficking and abuse of women and children”.

Last summer, Kolfage, along with Bannon and two others, Andrew Badolato and Timothy Shea, were arrested and charged with conspiring to defraud “hundreds of thousands of donors” through an online fundraising scheme that collected $25m. The men have pleaded not guilty, and their trial is due to start in May.

Now, Snipes, 74, and 67-year-old Pimentel, are in the news again. As thousands of migrants in recent weeks have crossed the US border, many of them encouraged by a partial change in rules enacted by Joe Biden, who said the most vulnerable asylum seekers should be permitted to wait in the US while their cases are processed, each has been working to help provide basic shelter and meals.

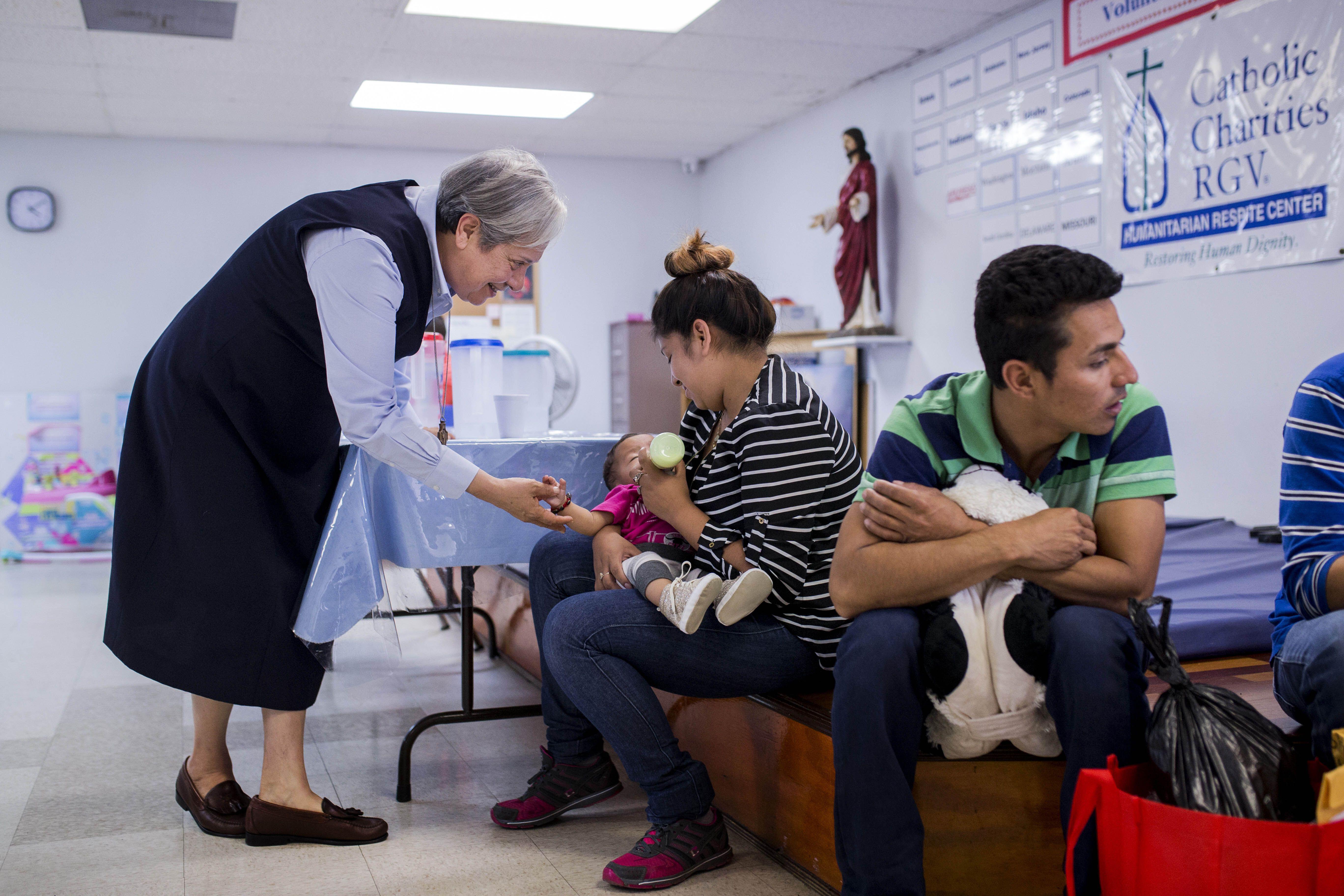

At the migrant respite centre, established at the Sacred Heart Catholic Church, located close to the bus station in McAllen, Pimentel has been overseeing with a soft voice, but firm hand, efforts to help hundreds of people arriving every day. Ten miles east, at the Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mission, Snipes has been finding room for the overflow, turning classrooms into bedrooms, and feeding scores from a simple kitchen, and the help of volunteers. He has been blessing them, praying for them, and helping dilute the stress, carried in the bodies of adults and children alike, by introducing them to the church’s donkey.

Moreover, both have been acting as advocates, not simply for the migrants currently in their care, but for those who passed through previously, and those who might do so in the future.

Standing among the migrants who Snipes is helping, The Independent asks him what gets lost in the political debate about immigration and the border.

“These are our brothers and sisters, mothers and fathers – these beautiful people,” he says. “It’s like Mary and Joseph running away from Herod. They couldn't manage to straighten him out and had to get away. He wanted to kill their baby and destroy their family. They had to get away. And that’s what these people are trying to do, struggling to survive.

“People know it in their hearts, but maybe it needs to be repeated – that to despise or disparage people who are weak and struggling to survive hurts them, but it hurts us more,” he adds.

Those around him certainly appear in need of help. Most are from Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala, countries which have long suffered from poverty, corruption, and political repression supported by various governments and gangs. In recent years, a new menace has descended upon parts of these countries: climate change, which has made the lives of farmers and coffee growers even more fragile.

The migrants carry just a smattering of belongings, a single change of clothes, perhaps, and a few toiletries, pushed into a sports bag or backpack, often donated by a charity. They tightly clutch vital paperwork in large manilla envelopes, which often have marked on them details of their next journey – “American Airlines, McAllen, TX, 7.40am”.

One woman, from Honduras, sits with her daughter. On her envelope has been pasted a printed sheet of paper with a message written in English in capital letters: “PLEASE HELP ME. I DO NOT SPEAK ENGLISH. WHAT PLANE DO I NEED TO TAKE? THANK YOU FOR YOUR HELP.

Another woman, Pearla Fernandez Milian, sitting quietly on a bench surrounding a humble play area as she watches over her children, says it has taken 23 days to reach this spot from Salamá, 100 miles from Guatemala City. She paid $12,000 to a people smuggler – coyote is the word used – to bring her and her three daughters. They crossed the Rio Grande in a boat at 11pm, and then walked to give themselves up to Border Patrol Agents.

While criminal gangs are present in many cities and rural areas in Central America, another burden for people to bear, there are none where she lives. But there are no decent jobs, not the kind that provide enough money to pay for rent, for schools, or for her youngsters, aged 4, 10 and 15, to visit a doctor. She readily admits the changes introduced by the Biden administration, encouraged her and others to try their luck.

“When Trump was president this was not possible. Biden is good,” says the 34-year-old, who is going to her sister’s home in Indiana.

Snipes, who likes Lone Star beer and country music, moved to the area in 1992 from San Antonio. He is said to belong to a religious movement known as Oblate priests, who arrived in South Texas in the late 1800s and were termed the “Cavalry of Christ”.

People know it in their hearts, but maybe it needs to be repeated – that to despise or disparage people who are weak and struggling to survive hurts them, but it hurts us more

He says everyone should be welcome at his church, or any church. As a result, sometimes he finds his congregation containing a mixture of migrants, CBP and ICE agents and others.

Marianna Trevino Wright is the executive director of the National Butterfly Centre, located in Mission, and works to protect the 340-odd species of the insect in the Rio Grande Valley. Two years ago, she worked with Snipes to highlight attempts by Trump supporters to buy private land along the Rio Grande to build a wall. Their efforts were eventually unsuccessful.

Wright says Snipes is intelligent and thoughtful, and takes his “commitment to serving Christ very seriously. And that involves serving everyone as if they might be Christ, and being responsible stewards of the natural world and other resources.”

She says she has asked him how he manages to preach to such an unlikely mix at his church: migrants, and the agents who might be seeking to detain them. “He says he welcomes everyone, but challenges some, saying ‘do you really think Jesus wants you to be a jerk’.”

Snipes’s senior pastoral assistant, Albert Solis, says there is no formal arrangement between his work, and that of Sister Norma, but that they help each other out “from time to time”.

If Pimentel is, by contrast, a little less colourful than Snipes, her dedication to helping the most vulnerable appears no less firm. A member of the Missionaries of Christ Jesus, a Catholic order formed in Spain in the middle of the 20th century, she was born in Brownsville in 1953, after her parents, both from Mexico, moved to the US and applied for residency. She was one of four children, and reports suggest she decided to pursue a religious life against the wishes of her family.

Once she did, she started working to help those in need on both sides of the US-Mexico border. Pimentel, who has degrees from St Mary’s University and Loyola University, Chicago, is fond of painting, and often does watercolours of the families who pass through her charitable centres. Some are sold at fund-raising events and one was presented to Pope Francis when he visited the US in 2015.

Much like Snipes, the nun places her faith, and the teachings of the Bible, at the very centre of her response to helping the migrants. During Trump’s presidency, she not only spoke out against his wall, but against his vision of who the migrants were, and why they deserved help, not demonisation.

On one of several visits Trump made to the border, the nun attended a roundtable discussion, and had hoped to change his mind. As it happened, she was not called upon to speak directly to the president. Those who did get to speak, appeared to simply repeat or reaffirm Trump’s view on the need for a wall. She told Texas Monthly that at the January 2019 meeting, nobody had said anything that contradicted him. “I think it was carefully planned out so that nobody challenged him. Nobody asked him anything different from what he thought.”

The Independent speaks to Pimentel outside the respite centre in McAllen, close to the bus station, from where many migrants embark on journeys to cities across the US, hoping to start new lives. One man, Miguel Gonzales, from Quetzaltenango, Guatemala, is hugging his child. He says he been travelling for 23 days.

“We walked across the river,” he says. “The water was very shallow.”

Pimentel says there have been several “surges” in migrant numbers, often attendant to political events in the US. One was in 2017, after Trump vowed to build a border wall, and another in 2019.

“We have traffickers who exploit these families, using a narrative to encourage people to come, saying this is the right time, saying the president is “opening the door”, which is not true. They’re using whatever can be exploited,” she says.

She says the tired and weary people inside her centres have astonishing stories to tell, both of how they got here and what they are seeking to leave behind. “The families have gone through great difficulties. They walk for many hours, if not whole days. Their feet are destroyed from so much walking. They sleep just about anywhere, on the ground, with animals, among the bushes and things,” she says.

“They're always hiding from people who might take advantage of them and many of them get caught. They have horrible stories.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks