A tour of Robben Island, 30 years after Nelson Mandela’s release

South Africa was a pariah nation in 1990, when Mandela was released. What does Cape Town look like now, asks Melissa Twigg

Thirty years ago today, Nelson Mandela stepped out of Victor Verster Prison and into Cape Town’s hot February sunshine. He was a free man for the first time in nearly three decades – and the waiting crowd broke into song as he stood on the steps and smiled. At a rally of 250,000 people outside City Hall later that day, he addressed the nation with a message of reconciliation. “Fellow South Africans,” he boomed, in his distinctive voice. “I greet you all in the name of peace.”

Mandela’s release symbolised a new dawn in South Africa – a country that in 1990 was still a pariah nation, banned from participating in global sporting events, with virtually no tourism industry and the spectre of one of the most repressive regimes of the 20th century hanging over it. Today, it is rightly beloved by visitors from around the world. But it is only by looking at the life Mandela led that we can really understand the still-fragmented nature of modern South Africa, as well as its humanity, warmth and generosity.

Cape Town is one of the world’s most photogenic destinations. Table Mountain looms over pristine beaches, jewel-coloured houses fill the inner city and vine carpeted valleys sweep through the suburbs. But on the city’s Atlantic Seaboard, the glamorous infinity pools and white sand beaches have a full-frontal view of Robben Island, the brutal prison that housed Mandela for 18 years.

Last month I went back to Robben Island for the first time in years. It was a hot January day and the island felt drier and more remote than ever, with the occasional seagull floating overhead, and the picture-perfect outline of Table Mountain framed across the sea. Mandela’s cell – with no bed, a single bucket and a bulb that burnt day and night over his head for 18 years – felt starkly claustrophobic by comparison.

In his memoir, Long Walk to Freedom, Mandela wrote, “It is said that no-one truly knows a nation until one has been inside its jails. A nation should not be judged by how it treats its highest citizens, but its lowest ones – and South Africa treated its imprisoned African citizens like animals.” Apartheid permeated every aspect of South African life, and jail was no different. Indian and mixed-race prisoners received double the amount of protein as their black counterparts, and black inmates were only allowed to wear short trousers, even in the depths of winter. White political prisoners were held elsewhere.

Zim, our 55-year-old guide, spoke movingly about his life as an inmate on Robben Island in the 1980s, and how he survived these inhumane conditions. Later, he gestured to a bleak limestone quarry on the side of the road. It was here, he said, that political prisoners toiled virtually every day of their imprisonment, digging up the stones that paved the road we were standing on. The relentless sun bounced off the white quarry walls, leaving Mandela and his fellow prisoners stricken with “snow blindness”, which damaged their eyes forever.

It was in this quarry that men such as Mandela and Walter Sisulu used their time to teach each other literature, philosophy and political theory. When they weren’t learning, they sang. “Songs were inspirational, they create the mood,” said Anthony Suze, a political prisoner on Robben Island for 15 years. “So if you want to go into a fight, you sing. That song becomes the opium that takes over the body, mind and soul.”

Music Beyond Borders, a South African organisation run by Janie Cole, has recently reunited a group of former political prisoners from Robben Island to record these songs of survival. I later watched them sing their haunting, hopeful melodies, their hands still mimicking the back-breaking work they endured half a life-time ago. “This struggle history as highlighted in the music and prisoner testimonies must be recorded before time runs out to preserve and celebrate it,” says Cole, “and above all to raise awareness and consciousness about historical crimes against humanity.”

Next to the Robben Island dock is a small town where the white guards and their families lived. The tennis courts were cracked, and the pink and white houses were covered in bougainvillea, but it was a world away from the barren, isolated cells around the corner. The tourists surrounding us were nearly all foreign, and as they introduced themselves to each other, I kept quiet; it was a difficult moment to be a white South African.

Lovely as Cape Town is to look at, if you want to understand the soul of South Africa, you need to go to Johannesburg. The Apartheid Museum will explain the tortured last century better than any book can and even the country’s Constitutional Court – which is open to visitors in the morning – lies on the same site as the Old Fort Prison, where political prisoners awaited trial during apartheid.

Liliesleaf Farm in Johannesburg is also open to the public. It became the clandestine headquarters of the ANC’s banned military wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe, and Mandela lived here in the 1960s, disguised as a member of staff working for a supposedly respectable middle-class white family. Years after his release, Mandela wrote Long Walk to Freedom at the Shambala Game Reserve, which is a two-hour drive north of Johannesburg, and he later spoke about the deep peace that came from falling asleep to the sounds of the African bushveld.

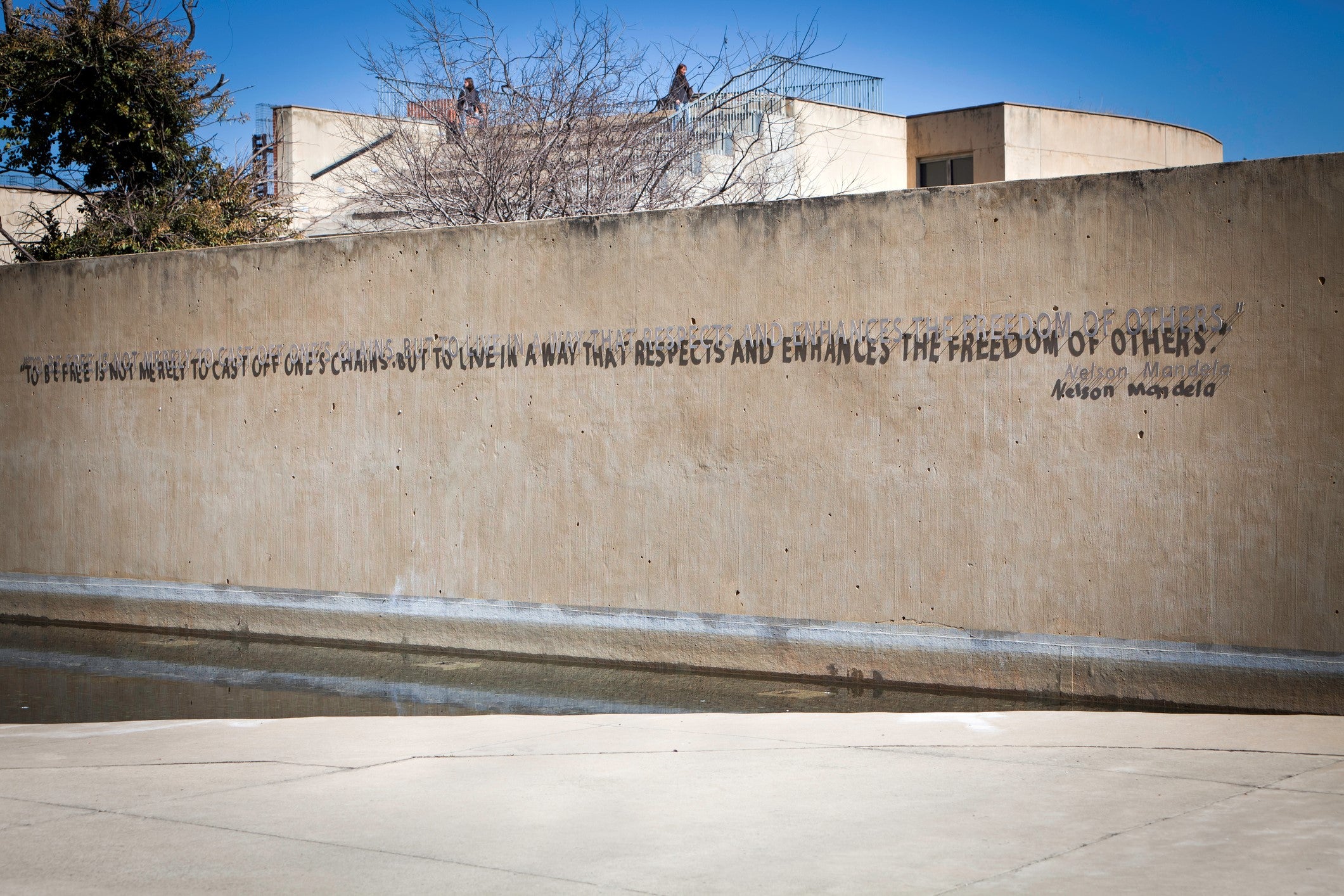

Statues of Mandela pepper the country. He looms large in Johannesburg’s Sandton Square, where businesspeople in navy suits eat sandwiches at his feet; in Howick, Kwa-Zulu Natal, a sculpture of his face marks the spot where he was captured by police in 1962. And on Nobel Square in Cape Town, Mandela stands alongside his fellow Nobel Peace Prize winners, FW de Klerk, Desmond Tutu and Albert Luthuli, under the shadow of Table Mountain – the small dot of Robben Island shimmering on the horizon behind them.

Travel essentials

Getting there

British Airways flies to Cape Town from London from £613 return, and Johannesburg from £516. From the US, South African Airways flies to Johannesburg from New York from around £700 return.

Visiting there

Donate to Music Beyond Borders here.

Visit Robben Island for the day with a specialist guide with Abercrombie & Kent.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks