How coral reefs are saving the Maldives

Claire Turrell joined a team of marine biologists to find out more about an innovative new scheme that could be the island nation’s saving grace

Marine biologist Tiana Wu kicked her legs and dove further towards the coral on the ocean floor. She had seen one of the Maldives’s unique sea creatures and wanted to share the experience. I followed her trail of bubbles through the cerulean-coloured water.

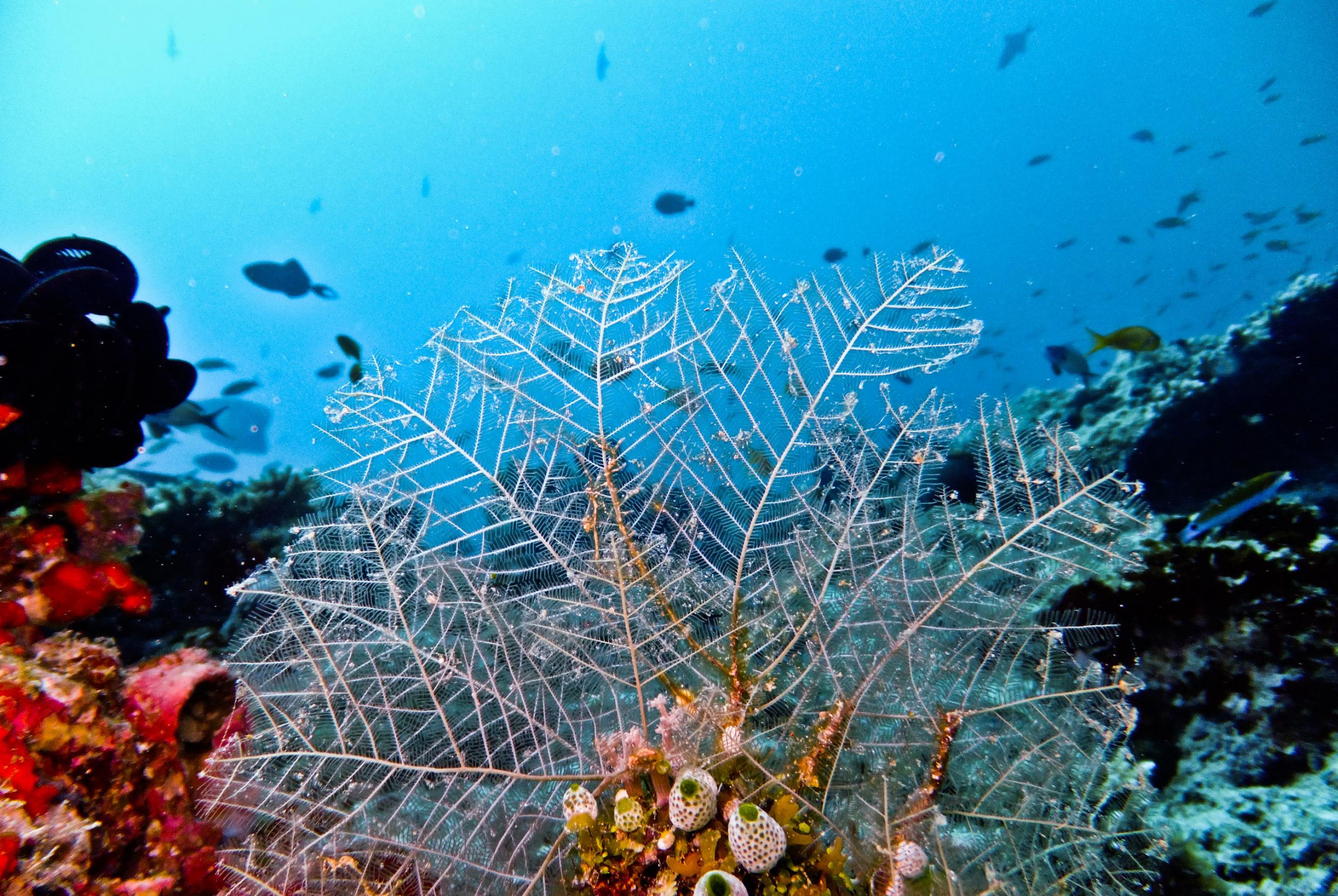

Neon parrot fish, painterly Picasso trigger fish and tiny monochrome domino fish danced around the coral beneath me. Amid the busy scene, Wu’s gloved finger pointed in the direction of a six-inch long pipe fish camouflaged against the rocks.

Yes, the pipe fish was indeed a marvel, but my attention was snatched away by the backdrop of white, dead coral that surrounded it.

One Palm Tree Island, off the coast of Gili Island, has suffered coral bleaching twice in the past 20 years. If the coral experiences stress due to an extreme and sustained change in temperature, it will expel the algae that lives within it, which causes the coral to turn white. And if the temperature does not return to normal, it could die.

The most recent episode was in 2016, when the large-scale ocean-atmosphere climate known as El Nino created a rise in sea temperature and wiped out between 50 and 80 per cent of all of the Maldives’s coral.

Sarah Davies, a UK marine biologist who has lived here for seven years, said the coral could have coped with a small spike in temperature – but after two months of record temperatures, the vibrant-coloured coral turned white.

“It looked like it had snowed,” said Davies.

Coral reefs are the rainforests of the sea. They only occupy 0.1 per cent of the ocean, but support 25 per cent of all marine species on the planet. The World Wild Fund For Nature (WWF) says the variety of life found on a coral reef rivals that of the Amazon.

Although El Nino has taken its toll, there is now a glimmer of hope.

The marine biologists at Gili Veshi have launched an innovative coral regeneration scheme, which will not only replenish the reef, but help protect the island. For not only does coral provide a home for marine life, it also provides the island with a natural barrier. But they need to move fast: the world’s lowest-lying country is threatened by rising sea levels and erosion.

“In 50 years, the Maldives could lose some of its smaller uninhabited islands to the sea,” said Davies.

Nature has already provided the solution. If its coral reefs are flourishing, the Maldives could be saved by this natural wall under the sea.

Under the coconut-leaf thatch roof of their marine biology centre, Davies told me more about their low-tech, but highly effective, coral line scheme.

The Gili Veshi team chose a sandy seabed near One Palm Island for their underwater nursery so they could construct the site without disturbing the reef. Unlike other regeneration schemes, where they grow corals on frames placed on the ocean floor, the coral here is grown on rope lines hung on wooden frames.

The suspended lines keep the coral away from predators on the ocean floor, such as the crown-of-thorns starfish and carnivorous drupella snails. The height allows the coral to bathe in the cool Indian ocean current, helping it to flourish. Positioning the coral in the current is also vital for coral spawning, so that the reef can replenish itself naturally.

The team initially gathered live coral for their rope lines from the broken pieces they found while diving; now they take coral cuttings from their nursery. They also rescued live coral from a neighbouring island, which was set to be buried by sand during land reclamation.

Davies and her team monitor the lines every three months, measuring and photographing the size of the coral and making sure the lines are free of algae.

“Once a week we scuba dive down to shake the lines in order to remove any excess algae that has grown, as this could smother the coral fragments,” said Davies.

Once the coral has matured, they will take it from their nursery and plant it directly onto the reef. Coral planting projects that use frames create new reefs with the help of the submerged frames, but with this scheme, the marine biologists are helping to replenish the natural reef with growing coral.

After six long years, they now have 193 coral lines. The team are able to transplant coral from their underwater nursery and are seeing it grow successfully on the natural coral reef.

Some of the corals grow faster than others. The pocillopora (boulder coral) takes a while to grow, increasing at a rate of 1cm per year, while acropora (branch like, bushy coral) can grow between 10cm and 20cm in a year – the team plant a higher proportion of the latter. When it reaches 20cm, it’s large enough to be transplanted.

The team started trialling a rope-based nursery in 2014 after reading about scientists using it in their research in the Philippines. But with El Nino in 2016, and failed attempts at replanting the coral on to the reef, the learning curve proved to be lengthy.

In 2019, they turned a corner after trialling new sites and adopting a new way of attaching the coral to the reef. By January 2020, the researchers were finally able to transfer the mature coral lines in earnest.

The team found a section of the reef that was less active with marine life, so the coral had a chance to take root. And instead of wrapping the ropes around the coral reef and hoping the coral would take root, they started to transfer the coral in clusters using epoxy resin.

“As they were in clusters, they had strength in numbers against the trigger and butterfly fish,” explained Davies.

The team are constantly adding to their knowledge. When El Nino struck, the Gili Veshi team were able to see that certain corals, such as porites rus and pocillipora, could handle the rise in temperatures. It gave the researchers the chance to see which corals are likely to persist in the warmer reefs of the future.

“It helps us to select more resistant types, enabling us to have strong resistance coral in our nursery, which we can later transplant on the reef,” said Davies.

The nursery has now become as active with marine life as the natural reef itself. Lionfish can often be found hanging on the frames, and juvenile reef top pipe fish and small yellow box fish will shelter under the coral lines. The nursery also has its own resident green sea turtle, who likes to take a nap on the frames.

The Coral Line scheme is showing how nature can fight back – as long as it’s being given a chance.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments