Learning the ancient art of Ebru in Istanbul

This traditional marbling is more meditation than artform, finds Punita Malhotra

Peering at the framed artefact, I ask: “Is that paper or marble?” “Both,” the tour guide smiles at my intrigued expression. “This is an ancient specimen of Turkish marbled paper called Ebru. Calligraphers used to inscribe elaborate patterns like these on books, imperial decrees and government documents to prevent duplication and tampering.”

My curiosity is piqued.

Quizzing continues while we drift through the dazzling Iznik tile-clad halls of the Topkapi Palace. I trace visions of a centuries-old art that travelled from Turkestan to Ottoman lands via the Silk Road and visualise master marblers and amateur apprentices devoting years to perfecting secret skills. I follow its reinvention as decorative art, believed to have inspired iconic European motifs such as the French Snail, the Spanish Wave, the Italian Vein and the Chevron. We discuss Ebru’s journey from esoteric to voguish, thanks to a listing on the Unesco Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, the fame of international celebrity artists such as Garip Ay and a burgeoning community of connoisseurs. And I learn that a capsule course on Turkish marbling in the heart of old Istanbul is no pipe dream for a wannabe designer or a newbie fan.

After all that, I’m excited enough to sign up.

Hello wispy clouds

Studio table, paint jars, horsehair brushes and an array of unfamiliar “equipment”… my teacher, Betul, helps me navigate this uncharted territory. Graduating from the Fine Art University in 1995, she worked with different marbling teachers before opening her own studio in 2010.

“The art of marbling is like meditation; it’s very relaxing,” she says. “You take a stroll in your inner world.”

I tune in and the dance of colours begins.

She blows on the colours… effortlessly adding more layers of complexity to the design with every move. I’m sold on the art therapy angle already

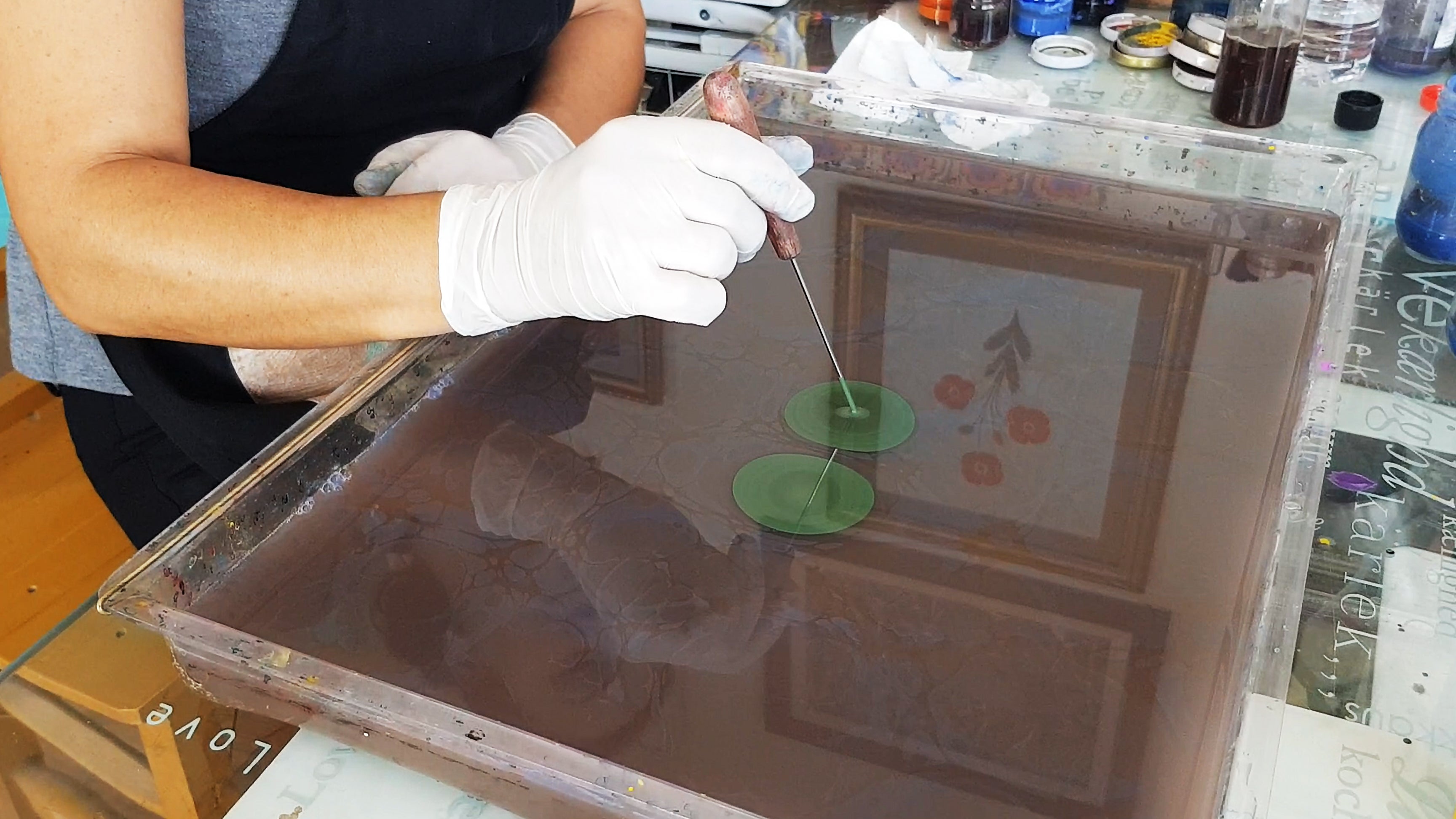

The canvas is a shallow tray of thickened water containing condensed herbal gum. Betul taps a long whisk gently, sprinkling drops of mineral pigments on to the water’s surface. They swell instantly into circles, floating on the oily surface, separated from each other, as if by private bubbles. It’s the ox gall added to the paint that creates the effect. Then, with precise hand movements, she skims her pen-like tools over the water, creating a floating picture. Slim stems elongate into veined leaves and rounded petals sprout from curling tendrils as she delicately nudges, pinches and stretches the paints into fluid shapes. She blows on the colours, slides pin-rakes through and zigzags wooden combs across, effortlessly adding more layers of complexity to the design with every move. I’m sold on the art therapy angle already.

Finally, she lays a sheet of paper on to the tray, patting it softly all over to prevent air pockets, then slides it off deftly, transferring the entire image from the tray on to the paper. And it’s a brand new, inimitable art piece of “wispy clouds”, true to its Persian name.

Now it’s my turn. I get to grips with the new tools, control hand pressure and speed, learn how the medium behaves and manipulate moving patterns (it’s all a lot more challenging than Betul made it seem). My teacher is encouraging, though.

“Learning Ebru requires more patience than skill,” she says. “The paints don’t always spread into the water as you wish, you must be patient. The process should make us happy, not the result”.

I adjust my expectations accordingly and decide to stick to abstract forms, observing, improvising, watching the design unfold tentatively. No pretty stems or dainty flowers yet but the composition is pleasing, at least to me. I’m pretty taken with my maiden artwork. It will give a new lease of life to the worn-out coffee tabletop in my home office, at any rate. Maybe I could find some complementing Ebru coasters or a lampshade in the Grand Bazaar?

A deeper love

Later, as I ogle the masterpieces displayed on the studio walls, I notice popular colours include light green, red and yellow. We chit-chat about classic motifs such as flowers, foliage, ornamentation and moon crescent. I pick up terms such as tarakli style (scallop), gelgit (zigzag), bulbul yuvasi (swirl) and hatip (scatter) and the 19th-century floral marbling technique, introduced by Turkish Ebru master Necmettin Okyay. His stylised versions of tulips, poppies, rosebuds, daisies, pansies and carnations would refashion Ebru for ever.

So what does it take to pursue this field professionally? At least two years’ work to fully learn the art of marbling, according to Betul. To become a teacher, one must graduate in traditional Turkish arts from the Fine Arts University or train with a master craftsman until he/she thinks you’re ready. But, like any other craft, formal training is just the start. From there, individual self-expression carves out the direction.

“Every artist’s source of inspiration is different. Turkish marbling opens one’s mind to an infinite sea of creative possibilities. Each marbling paper is unique, just like the artist who creates it.”

Having been witness to the ethereal love affair between creator and canvas in a Sultanahmet studio by the blue Bosphorus, I know exactly what she means.

Travel essentials

Getting there

Trying to fly less?

Travelling to Istanbul from the UK is possible by train; the journey takes about four days on a route that run from London to Paris, Paris to Budapest, Budapest to Bucharest and Bucharest to Istanbul.

Fine with flying?

Turkish Airlines flies direct from London Gatwick to Istanbul.

Staying there

The Intercontinental Istanbul (Beyoglu) has doubles from €114 (£97.30).

More information

A Turkish Paper Marbling (Ebru Art) workshop with Turkish Arts costs €50.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks