How to explore Beethoven’s Vienna

The Austrian city is still celebrating the famed composer’s 250th birthday. Here’s how to get in on the action, writes Mark Stratton

Goethe relates a telling anecdote about the indomitable spirit of Ludwig van Beethoven – whose 250th birthday is still being marked this year after the pandemic led to the cancellation of a number of events in 2020. Witnessing Beethoven fail to step aside for passing nobles, Goethe asked why he was so disrespectful. “There are countless nobles, but only two of us,” replied the cocksure composer.

Guided by “the light of genius”, Goethe also wrote, Beethoven rose from troubled beginnings (his father was an alcoholic and his mother died prematurely) to arguably become classical music’s greatest composer. Born in Bonn in 1770 and having given his first public piano recital aged six, he set off for Vienna in 1792, where he lived his remaining 35 years, producing nine thunderous symphonies, an opera, and timeless piano concertos and sonatas.

There are countless nobles, but only two of us

He was misanthropic, short-fused, often depicted as messy and increasingly deaf: a disability that gnawed away at this pitch-perfect maestro and saw him retreat from society. During his life in Vienna, the restless Beethoven moved 68 times, ensuring his lasting omnipresence throughout the Austrian capital.

Now that Austria’s on the UK green list – and British travellers are no longer banned – here’s how to enjoy a break in celebration of all things Beethoven.

Bed down

Base yourself in hip District 6, Vienna’s own approximation to Shoreditch, at the cosy Hotel Beethoven, built after the composer’s death. Yet Beethoven knew this area: opposite is Theater an der Wien where he lived between 1803-4 producing his only opera, Fidelio, premiered here to initially lukewarm reviews. The hotel’s third floor is Beethoven-themed and my room (305) was decorated with bold-coloured wallpaper reminiscent of the Viennese Biedermeier period contemporary to him. Downstairs, the glossy Bösendorfer piano that is property of the aptly named hotel owner, Barbara Ludwig, fires up every Sunday at 5.30pm for a free recital of Beethoven’s chamber music complete with interval champagne. Doubles from €120, B&B.

Museums

Piece together the octaves and semibreves of Beethoven’s life at dedicated museums throughout Vienna. Beethoven Museum (entry €7) in Heiligenstadt is 25 minutes from the centre by the number 37 tram. It’s now in the suburbs, but in Beethoven’s time the rooms he rented here were his summer countryside retreat, from where he took long country walks and enjoyed the spa waters. The museum’s most important item is a facsimile of his heart-wrenching “testament”, written here in 1802 to his brothers putting his distemper down to the turmoil of increasing deafness and stating only his art held him back from suicide. At another former residence, Pasqualati House (entry €5), he worked on his 5th, 7th, and 8th symphonies. The fourth-floor museum came about in tragic circumstances in 1941, as the Nazis evicted the resident Jewish family to Auschwitz. Exhibits include love letters; Beethoven’s experiences of unrequited love with social “betters” prompted his composition here of the hauntingly sad “Für Elise”.

Café culture

Beethoven insisted upon 60 beans ground into each cup of coffee and participated in the flourishing coffee-house culture of his day. Most famous is the late 18th-century Café Frauenhuber, where in 1797 the caffeinated virtuoso followed Mozart in playing here: his quintet for fortepiano with four horns. Under the same unpretentious white vaulted ceiling Beethoven would purr at today’s plum strudel and Viennese-style coffee served in a glass cup with frothed milk on a silver tray. Another ancient establishment is Griechenbeisl Inn, a rabbit warren of rooms, where Beethoven’s signature can be found inscribed on a wall alongside Mozart’s and Wagner’s.

Music man

Classical music and opera can be heard throughout the year in Vienna. The colossal 1860s State Opera House was built after Beethoven’s death and has featured regular performances of Fidelio. These days hawkers mill around the opera house donning Mozartian powdered wigs to tempt you to concerts at venues throughout Vienna. I paid €39 for an hour of classical hits, getting the Stars-on-45 treatment at the sumptuously baroque St Charles Church. A youthful ensemble rattled out Beethoven’s 5th (you know the one: da-da-da-daaaaa) plus Schubert’s emotional “Ave Maria” and Vivaldi’s Four Seasons.

High barnet

Head to Beethovenplatz for a magnificent bronze of the composer sculpted by Casper von Zumbusch in 1880. Beethoven sits atop a plinth looking dismissively down upon us atonal mortals below; his luxuriantly tousled barnet possibly explaining why he chose to defy the pervading convention of wearing a wig.

Palace Eroica

Beethoven received fiscal support from wealthy patrons and his music was routinely performed in chamber venues. Enshrining this association is the unmissable palace, now the Theatre Museum, of Prince Lobkowitz, Beethoven’s principal patron. There’s a Sistine Chapel “wow” factor about the frescoed ceiling of the palace’s divine Eroica Hall, named after Beethoven’s 3rd symphony, which debuted here in 1805. He originally dedicated it to Napoleon but backtracked in a pique of rage, disillusioned by Bonaparte’s warmongering.

Sonic boom

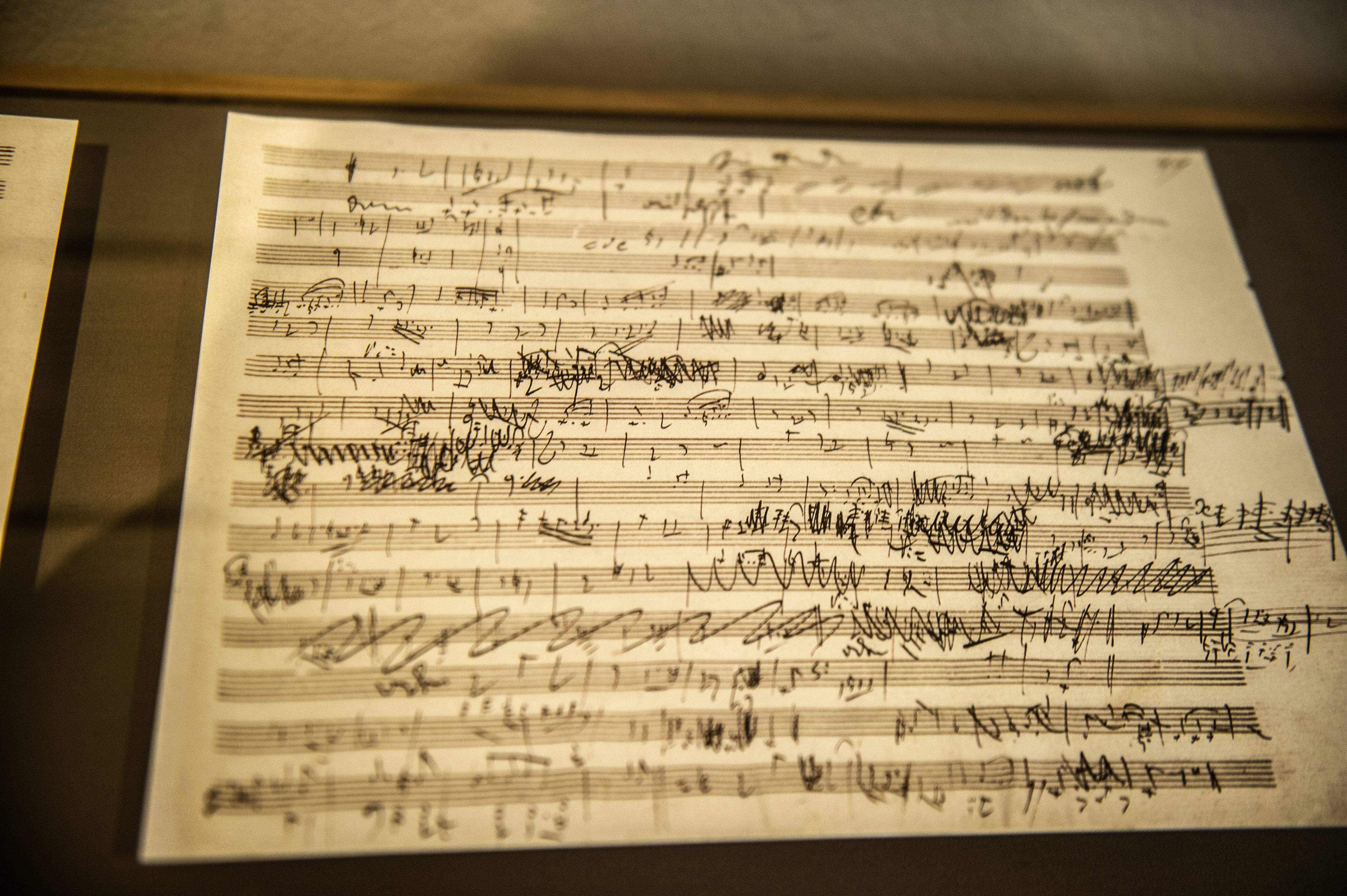

Haus der Musik (entry €13) is an innovative interactive museum Beethoven would’ve loved because it makes sense of what numerous doctors could not cure: his deafness. When he wrote his 9th symphony (featuring the currently out of vogue EU anthem, “Ode to Joy”) in 1824, he was completely deaf. The 2nd-floor “Sonosphere” explains sound wavelength experiments and examines the different stages of hearing loss he experienced. The floor above is dedicated to Viennese composers and exhibits include notebooks Beethoven used to communicate once deaf. They show he was partial to bread soup and the liberal imbibement of wine.

Secession

Fans of Jugendstil will be dazzled by Gustav Klimt’s Secession exhibition space (entry €9.50). The white-cubed exterior with gold-leaf dome was inspired in 1898 by Klimt and his Association of Visual Artists (the Secessionists) who reacted against traditional art-galleries’ “jumble of mediocrity”. In 1901 Klimt and his acolytes created an extraordinary mis en scène frieze in the basement dedicated to Richard Wagner’s operatic interpretation of Beethoven’s 9th. This spellbinding chef d’oeuvres of Viennese art-nouveau features motifs of suffering, sickness and lasciviousness, portrayed by genii, gorgons, lovers, and armed knights. The increasingly isolated Beethoven might have identified with the figure of a wretched grieving girl, who appears removed from the other figures...

For the love of wine

An autopsy showed Beethoven died from liver cirrhosis likely caused by excessive alcohol consumption; he was partial to cheap wine. A still functioning tavern he frequented is Mayer am Pfarrplatz where, unhelpful for his liver, he resided in 1817. It has a pleasant, leafy courtyard for drinking and dining al fresco after 4pm. Austrian white wines have moved on since Beethoven’s day and he’d certainly enjoy partaking in a silky smooth Hitzberger Gruner Veltliner at Wein & Co: a wine-shop chain with onsite bars where you pay no extra to drink bottles purchased in their shop.

The end

Some 20,000 Viennese bade Beethoven farewell when he died in 1827. He was actually buried several times before final interment in 1888 at the remarkable Zentralfriedhof cemetery, a who’s who of Austrian greatness. Ride tram number 71 to Zentralfriedhof Tor.2 and seek group 32a tombs, signposted musiker. Beethoven’s marble-white edifice is decorated by a golden lyre, yet this is just the start. Next door is Schubert, who desired to be buried alongside him, and in front, Mozart. Search around a bit and you’ll find Brahms and Johan Strauss. He rightly rests amid greatness.

Travel essentials

Visit austria.info for more information. A Vienna Card secures visitors discounts on museums and transport.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks