Tom Stoppard: What the pandemic reveals about the value of the playwright’s art

‘Leopoldstadt’ was supposed to be Stoppard’s swansong – but even coronavirus hasn’t stopped him, writes Paul Taylor

In this global pandemic, a person with a gambling bug is spoilt for choice. You can be sure, for example, that some enterprising operators will already be taking bets on which West End theatre production will resume business once the all-clear sirens sound, in what will be an inevitably uncertain summons back to the theatre-going fold.

I can’t be alone in thinking that sitting atop the pile of dead certs will be Leopoldstadt, the latest play from Sir Tom Stoppard, the theatrical big-hitter par excellence. Leopoldstadt follows the fate of two haute bourgeois Viennese families, predominantly Jewish though some members have married Catholics, in the first half of the terrible 20th century which accelerated into nightmare. It’s produced by the redoubtable Sonia Friedman and staged by Patrick Marber, author of the indelible Closer (1997), whose prowess as a director has become as electric as his accomplishments as a dramatist. The drive and involvement of this pair betoken a palpable labour of love.

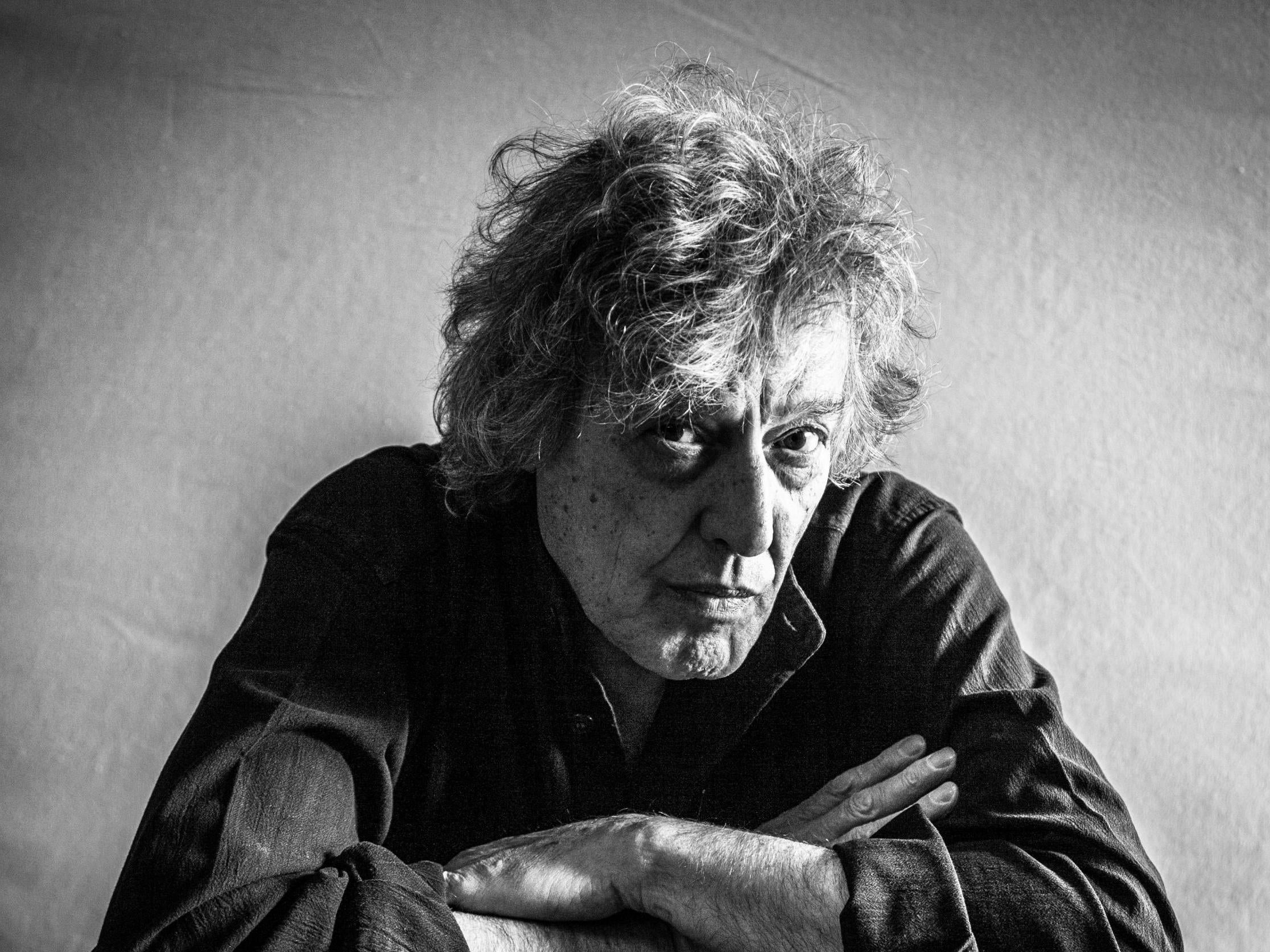

Leopoldstadt enjoys another distinct advantage. Now over 80, Tom Stoppard still treads an unfeasibly high wire of intellectual razzle dazzle while maintaining a rumpled rock-star resemblance to Sir Mick Jagger. There are not many people in this exclusive group – just as there are restrictions to the number of people (24 in the Commonwealth) who can, at any one time, be admitted to the Order of Merit. In 2000, the Queen welcomed Sir Tom to this rarefied enclosure.

Leopoldstadt received a predominantly positive press (it was hailed “a masterpiece” in my five-star review in The Independent). Taking their cue from the 82-year-old author, who had suggested that it might be his last play, many reviews struck an elegiac note. My conclusion was more upbeat: “Leopoldstadt would make a refulgent swansong for the octogenarian writer, just as it is destined to make a great film for Spielberg. But let us hope that its deserved success will give Stoppard a new lease of creative life in the theatre.” How ironic those words, published on 12 February of this year, sound now. Few people had foreseen a global pandemic (some culpably failing to do so, though briefed). No one could possibly have predicted that Stoppard would be making so early a re-entry into our dramatic culture, nor one that was both so weirdly and arrestingly topical and shaped, in its hybrid format, by the exigencies of the crisis.

A Separate Peace is a very early, half-hour television play first broadcast on 22 August, 1966, in the same week that theatregoers at the Edinburgh Festival got their first glimpse of Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead. The latter is the play – set in the wings of Hamlet – that would soon make the 29-year-old author’s name. Earlier this month, A Separate Peace resurfaced as an online reading. Under the artful, poetic direction of Sam Yates, a mouthwatering cast including David Morrissey (Hangmen, The Walking Dead), Denise Gough (an actor who matchlessly combines the sensitive and the combatively caustic – and two-time Olivier Award winner for the National Theatre’s Angels in America and People, Places and Things), and Jenna Coleman (Doctor Who) – each sequestered in their isolated locations – communally created this new-look revival.

Produced by John Schwab and Matt Humphrey, A Separate Peace was the first in an innovative series of “Remote Reads” designed as a staggered sequence of one-off events. Rethinking the parameters of live theatre-going in quasi-televisual terms, they are designed to raise money for actors and creatives who are struggling because of the pandemic. A sense of anticipation was fomented by the buzz of pre-show music. There were no overpriced programmes and no queueing for warm white wine and/or the ladies’ loo. You’d have to have made your own arrangements if you wanted that particular kind of nostalgia. But just as Leopoldstadt brought the audiences in Wyndham’s Theatre to their feet (and will do so again), so I found myself wanting to organise my own solo standing ovation at the close of A Separate Peace. It had proved to be a most pleasurable and thought-provoking experience. There are feats of selfless kindness and heroism that are without precedent also.

It would embarrass Stoppard to hear his plays are now forced to bask in the reflected glory of morally admirable gestures. But it is worth pointing out that it has never been possible before the current crisis to mount such a piquant “progress report” on a playwright of his stature. His last stage play is still in our minds and hearts and destined, in one hopes the not-too-distant future, to resume its premiere run. Then, suddenly, with what might feel like precipitate haste, we are confronted by an early work, written for a different medium and disseminated in the way all art has been during this global pandemic – online. Does this teach us anything of value about his art? I think it does – both in the sense that it makes us want to reappraise the avowedly apolitical stance of early Stoppard works, and because the interrupted run of Leopoldstadt gives us the opportunity to ponder its virtues more closely.

The title A Separate Peace might lead one to expect a play concerned with the tribulations of international diplomacy. In fact, the title is deeply ironic. The main character, John, signs himself into a private hospital one night, not because he is sick but because he wants to sink into a routine that requires him to do nothing and makes no demands of him. As a citizen unwilling to accept public obligations, he is a passive-aggressive non-starter. Evidently never having read the faintest shred of the Beveridge Report, let alone the The Communist Manifesto, he has saved his money so as to purchase this chance of an opt-out from duty and care. “But there’s nothing wrong with you!” exclaims the exasperated matron, who was played by Stoppard’s son Ed in Sam Yates’s version. “That’s why I’m here,” John explains. “If there was something wrong with me, I could get into any old hospital – free. As it is, I’m quite happy to pay for not having anything wrong.”

At a time when people are stampeding to their front doors to cheer out gratitude to the frontline workers of the NHS, John’s quietist position is not exactly calculated to be popular with today’s viewers. It’s possible that the audiences in 1966 surmised that the main butt of the joke was the medical staff and their deformation professionnelle – needing to pin a nefarious motive and identity on John. They’d rather suspect him of being a train robber, embezzler, or returned forger than accept his less complicated account at face value.

But it’s a truth about most worthwhile drama that its personality, priorities and meaning alter and develop over time. There’s a fundamental instability in the piece, in which John’s ambitions are seen to be weirdly self-defeating. They are not so much above or beyond the conformist herd as in variance with it. To humour the matron, he busies himself painting his walls with depictions of the world beyond his windows. If he is supposed to epitomise the artist, it’s as a suffocating synthesis. Figurative art is supposed to bring a breath of fresh air into the hermetic world of abstract painting. But John just paints what he sees outside the window – effectively negating the outdoors by bringing it into the hospital room.

Yates found pleasingly subtle, poetic ways of bringing out the sense of internal dislocation. In the less deftly handled of these Zoom-assisted charity get-togethers, the quartered split screen can remind you of editions of Blankety Blank or University Challenge. Yates’s production recalled neither Les Dawson nor Bamber Gascoigne, but the video artist Bill Viola, if he could be imagined working in monochrome. The personnel were black-garbed figures set in relief against white walls. The occasional emptiness of the cell-like spaces generated a sense of unease about who or what might materialise next in those vacated areas. I felt a frisson at certain moments of the underrated 19th century painter Vilhelm Hammershoi, the Scandinavian laureate of muted isolation and of those reversals between inner and outer loneliness that can wash over you.

James Saunders (1925-2004) was a leading exponent in the British wing of the Absurdist school of drama. He meant a lot to Stoppard, who let it be known that it was Saunders’ play Next Time I’ll Sing To You that got his own creative juices flowing. Of his young admirer, Saunders was later to say that he is “basically a displaced person. Therefore he doesn’t want to stick his neck out. He feels grateful to Britain because he sees himself as a guest here, and that makes it hard for him to criticise Britain.” That view rests on assumptions that lose battery power over the years. Such as the idea that the only kosher form of a political playwright is one who leans to the left. Or that Absurdist drama can’t have as cutting a political edge as the drama of fully paid-up commitment. In retrospect, this line on Stoppard looks a little parochial and behind the curve. It was on the fight against totalitarianism in eastern Europe that Stoppard had his eye.

This is hardly surprising. He began life as Tomas Straussler in 1937 in the Czech town of Zlin, and was barely 18 months old when his family were forced to flee from the Nazis. They took refuge in Singapore, only to be evacuated before the invasion by Japan. His doctor father, who had stayed behind to help, was killed when the Japanese bombed the ship on which he was trying to flee. Tomas and his brother were evacuated to India with their mother, where she married Kenneth Stoppard, a major in the British army. In 1946, he brought them all to Britain. Here, as he has said, Englishness fitted Stoppard like a comfortable coat. His mother’s memories of her Jewish lineage faded like photographs left out in the sunlight or shoved under a cushion away from risky, prurient curiosity.

This situation has a bearing on both the works under scrutiny here. The link is very obvious in the case of Leopoldstadt and more a question of how a new format can jolt one into new perceptions with regard to A Separate Peace. Stoppard continued to make jokes about being a bounced Czech after he had become friends with playwright (and future president) Vaclav Havel at the time of the Charter 77 movement. And when his play Rock’n’Roll was mounted at the Royal Court in 2006, it was only the second time that he had written a work partly set in former Czechoslovakia.

Stoppard had the option of writing an autobiographical piece that focused on the fate of his own forebears. Instead, the family on stage in Leopoldstadt spring from his imagination – an imagination informed by extensive, humane research into Vienna and its Jewish community, from the time when it was the city of Freud, Mahler, Klimt and Schnitzler. We come to feel for these people as if their idiosyncrasies, tics, strengths and failings have the throb and disputatious whirr of lived actuality. They refuse to be simplified into being first and foremost specimens of victimhood.

The invented nature of the family trees is arguably one of the sources of the play’s emotional power. Musing on why, I could not get a particular song out of my mind. It was “Little Green”, one of the tracks on Joni Mitchell’s 1971 album Blue, on which her signature emotional insight and creative courage surpass themselves.

Although the autobiographical background to this achingly beautiful song would only become known to the public much later, it is evident that the dramatised voice in “Little Green” is that of the mother of an illegitimate baby girl (the father is the “non-conformer” who has scarpered off to the warmer climes of California). The mother has signed over papers to the adoption agency and now speculates about a future in which she will play no part in the daughter’s life. The speculations are piercing in their mixture of stoic pain and open-minded refusal to be tethered to pessimism: “Just a little green/ Like the nights when the Northern Lights perform/ There’ll be icicles and birthday clothes/ And sometimes, there’ll be sorrow.”

The scenario in which a mother has to give up her baby is of importance in both Mitchell’s and Stoppard’s work and imaginative hinterland. It proves to be the crux of The Hard Problem, his 2015 play about the nature of consciousness. The protagonist, a female neuroscientist, wants to show that the phenomenon of altruism is real and disprove the genetic determinism of evolutionary biology. The play starts off with a long altercation between this woman and her boyfriend, who is bumptiously dedicated to the latter theory. For him, a painting such as Raphael’s Madonna and Child should be more accurately labelled “Woman Maximising Gene Survival”. The play’s twist is that the female scientist knows from hard experience what she is talking about, having had to give up an illegitimate baby herself. The Hard Problem teems with trenchantly expressed points of dispute. If it can’t be counted as one of Stoppard’s best plays, it is because it depends, plot-wise, on a massive coincidence and does not sufficiently leave you guessing where the author’s own sympathies lie.

Cut to Leopoldstadt. My contention is that while it does not deal with altruism discursively, it goes one better by being a revealing example of altruism in action.

James Saunders, who had a big impact on the early Stoppard, continues to lodge in his mind. In a lecture at New York’s Public Library, Stoppard included a long quotation from Next Time I’ll Sing to You. The passage is about how, behind everything, lies grief. The speech deploys the metaphor of the ornamental pond and the things that may be lurking in its murky depths – “You can sometimes see through the surface of an ornamental pond on a still day, the dark, gross, inhuman outline of a carp gliding slowly past; when you realise suddenly that the carp was always there below the surface, even while the water sprinkled in the sunshine, and while you patronised the quaint ducks and the supercilious swans, the carp were down there, unseen. It bides its time, this quality… The name of the quality is grief.” It is surely no accident that he delivered this lecture in 1999, the year that he started to open up about the extent of his Jewishness, most prominently in a long autobiographical essay published in Talk magazine, excerpts from which are reprinted in the programme that’s on sale at the Wyndham’s production of Leopoldstadt.

It might be construed as presumptuous of me to be arguing here that Stoppard, somewhere in the strange barometer that is the body, had a strong premonition that members of his mother’s side of the family were Jewish and would have been eliminated. It is often said of the altruistic impulse that it shades off as we move outward from kin. We are less solicitous of community than of family and arguably less of nation and race. After an antisemitic holocaust, are you kidding me? No – and especially not if you factor in the fear and risk that might make secrecy and evasion operate like second nature in post-war Britain.

In generously giving birth to a second imaginary family in Leopoldstadt, Stoppard adds to the ranks of European Jewry who are to be honoured and mourned. It is salutary, too, that he makes some scathing points about the limits to the liberal fellow feeling America was prepared to bestow with regard to refugees and displaced persons, and about the self-deceived propaganda about how post-war Austria was supposedly rigorously de-Nazified. “Fidelio will be the first performance in the new opera house, conducted by an ex-Nazi,” a survivor of Auschwitz noted drily. He implies that there will be something inherently compromised about an opera that celebrates liberation being produced under the baton of such a man.

A short, calorific paper could be written about the connection between Stoppard and sugary stodge. There is a delicious line in his 1997 play The Invention of Love where Oscar Wilde, now in post-prison exile in France, describes some unexpected treat as “like getting an extra slice of childhood”. I think it very moving that towards the end of Leopoldstadt, there is a reprise – presented as a mix of objective rerun and of subjective recall – of the incident that made Rosa bawl with shame when she was a little girl: her failure to remember that she had hidden the matzo under the piano lid.

I expect that among the people who flock into Wyndham’s for Leopoldstadt when it is reopened will be quite a few second-timers. The richness is a lot to take in in one go. Meanwhile, the hiatus has given us the occasion for further reflection on it and the chance to see how an early Stoppard work comes across when presented, perforce, with a new techn-savvy sensibility.

His mastery of the medium of radio has been bitingly manifest too since the lockdown began. In early May, Radio 4 broadcast The Voyage of the St Louis, his new adaptation of Die Reise Der Verlorenen (the 2018 stage play by the versatile and celebrated German writer Daniel Kehlmann). The material is based on a terrible real-life story. In May 1939, the eponymous liner sailed from Hamburg, Germany, to Havana, Cuba. Almost all of the 937 passengers were Jewish refugees in flight from the Third Reich.

There’s an obvious tension in the question: did the liner arrive and did the Cuban authorities allow the refugees to disembark? But Stoppard’s version jettisons that tremolando aspect and instead gives soberingly playful priority to another key feature of the material. Since this is a true story with a known and verifiable outcome, he unfolds it on the basis that it can be told by the voices of the people who went through the experience. Sometimes arguing over contentious claims and vexed interpretations, these voices deliver the story as if from a posthumous, beyond-the-grave perspective. That’s the potent framing device.

Heralded by a piercing whistle and the querulous lines “Can you hear me? Is this an echo?” the first voice to obtrude itself comes as a sullying form of radio interference. It belongs to Otto Schiendick, whose snide, sneering tones, emanating from the afterlife (and brilliantly evoked by Paul Ritter), instantly establish him as the archetypal, cocky official in a local branch of the National Socialist party. He’s been sent by German military intelligence on a mission to smuggle three capsule tapes to Hamburg from Havana. It sounds like a trope from a bad spy movie. It is, however, the flat truth. Along with his seething, ill-disguised antisemitism, Schiendick needs the liner to sail back to Germany, regardless of the eventual fate of the Jewish refugees.

Stoppard deploys this artfully. He elects himself the master of ceremonies of this sound-only event. “You want to know when the scene changes,” he tells the listener. “I’ll give you a clue...” and there’s a sudden lurch into the sound of a Latin American big band. He is insinuatingly sure that we would have been no better than he was. How do we know we’d have done differently? Then his circular argument tightens round the neck like a noose. Even to wonder about such a question is incriminating. Presenting the story as a fate foretold that leaves some key questions unanswered has the effect of making the voyage feel even more nerve-rackingly pervaded by doubt. And giving Schiendick so recurring a voice gives a suffocating dimension to the terrible sick-joke Nazi stitch-up. It was planned as a huge publicity coup that Cuba and the US would turn the Jews away. “No one wants them,” is the idea that the Nazis want to propagate, with Germany posing as the only nation prepared to “take care” of them, in the lethal sense of that idiom.

Stoppard’s methods highlight the deeply topical resonance. Refugees are regarded as charity cases. Giving foreigners succour is not calculated to be a vote-winner, and it’s their future electoral prospects that preoccupy the incumbent administrations more than human justice. The radio format, in which successive endings can be quickly overtaken by the latest events, allows Stoppard to emphasise the bleak irony. To be allowed to land by some western European countries rather than go back to Germany would turn out to be only an interim respite, as those countries came under Nazi occupation when the world went to war so shortly afterwards.

In 1976, Lew Grade had packaged the story into a star-studded feature film. Faye Dunaway brought her slightly zombie-like drop-dead allure to the role of the wife of a formerly top Jewish doctor, now demoted and elegantly harrowed. It is not a complete write-off: co-starring everyone from Max von Sydow (as the decent, conscience-stricken captain) to Orson Welles as a cue card-scanning, bizarrely pontifical corrupt Cuban minister. There is one very good scene when the romantic comedy that they have come to see in the ship’s movie theatre is prefaced by a piece of Nazi propaganda. Confronted by the spectacle of Hitler in full hectoring harangue, the Jews leave in disgusted dribs and drabs.

Stoppard’s radio treatment rejoices in many of those tellingly self-reflexive moments. You could trace a direct line back to the precocious prowess of his first forays in the medium in the mid-1960s, fostered by John Tydeman, the legendary director of radio drama, who died very recently. In If You’re Glad I’ll be Frank, a man realises the speaking clock is his former wife and is stirred into intervening; in The Dissolution of Dominic Boot, a man rides round in a cab trying to raise the fare to pay the driver. Brought home to you more closely by the medium of radio is that every second counts. Man is born free and is everywhere on a metre.

And so, with more sophistication and a categorically unfanciful story, we proceed to The Voyage of the St Louis. What a year the dramatist is having. Two ace new pieces and a forgotten piece from his back catalogues rebirthed in a powerfully revealing light. If asked to report on Stoppard’s progress through the pandemic, a teacher of the old school might be moved to say: “Couldn’t do better.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments