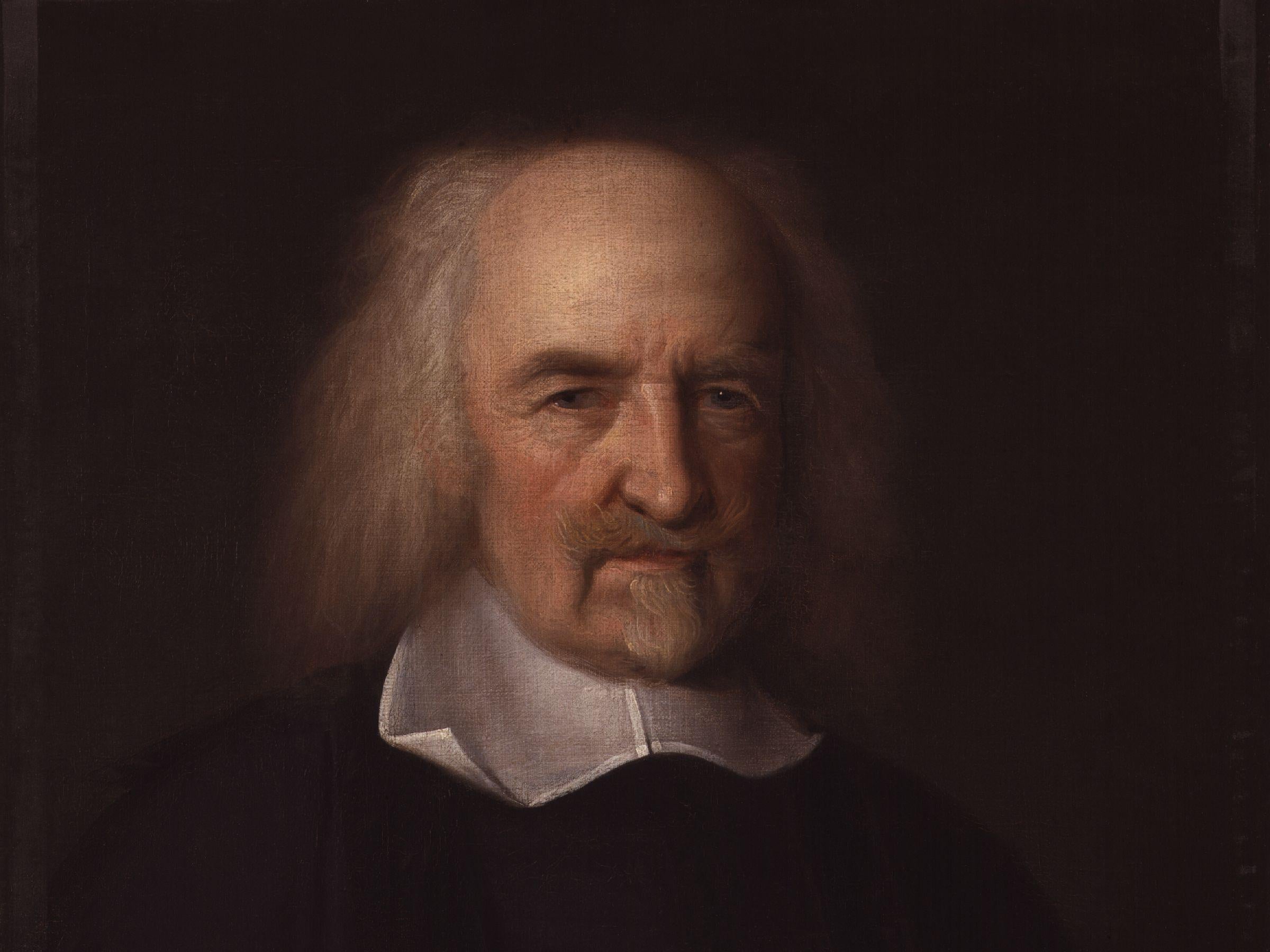

Thomas Hobbes: The most annoying philosopher of all time?

Our series moves on from the Renaissance and into the 17th century, starting with Thomas Hobbes who found a way to annoy almost everybody

It is difficult to have anything but a great deal of admiration for someone who managed to annoy as diverse a group of people as did Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679).

Parliamentarians were annoyed by his claim that the king’s right to rule is absolute, and monarchists by his suggestion that the root of this power is not divine but granted by the people. Hobbes annoyed mathematicians by insisting in the face of overwhelming criticism that he had squared the circle. He annoyed Descartes by offering profound objections to his views shortly before the publication of Meditations on First Philosophy. He annoyed at least one bishop with his position on free will and conducted a lifelong public and sometimes acrimonious debate with him on the subject. He annoyed the Church by arguing, among other things, that the king is in charge of the interpretation of scripture and atheists by taking the sacrament when he mistakenly thought he was about to die.

Proof that a lecturer had indulged in “Hobbism”, a byword for atheism, was grounds for dismissal during Hobbes’s lifetime. The possibility that Hobbes had annoyed even God was, for a time, seriously entertained. Following the Great Fire and the Great Plague, parliament wondered whether Hobbes’s writings had provoked God’s retribution and were somehow responsible for London’s disasters. A committee was set up which eventually demanded that Hobbes stop publishing.

Hobbes did not annoy everyone, however, and counted among his friends and supporters Gassendi, William Cavendish and at least one king. He was welcomed into the intellectual circle of the Abbé Mersenne, tutored Charles II, worked happily with Francis Bacon and exchanged views amicably with Galileo. And of course, he was concerned with more than just annoying people. He has been called, with some justice, the father of modern analytic philosophy, and he certainly ushered in modern political philosophy and social theory as we know it, breaking with traditional or mystical views of the origin of political power and turning instead to reason for its justification.

According to a story Hobbes himself did much to perpetuate, he was born prematurely when news of the approaching Spanish Armada frightened his mother into an early labour. His father was a vicar who fled the family home in some disgrace following his part in a brawl on the steps of his church. The young Hobbes was taken in by a well-to-do uncle, who saw to his education, eventually sending him to Oxford. Hobbes found lectures at university tedious, but following his graduation, he had the great fortune of becoming tutor to the son of William Cavendish, which gave him the the use of a splendid library and the promise of travel.

The natural condition of human beings, that is to say, ungoverned human beings, is war, ‘every man against every man’

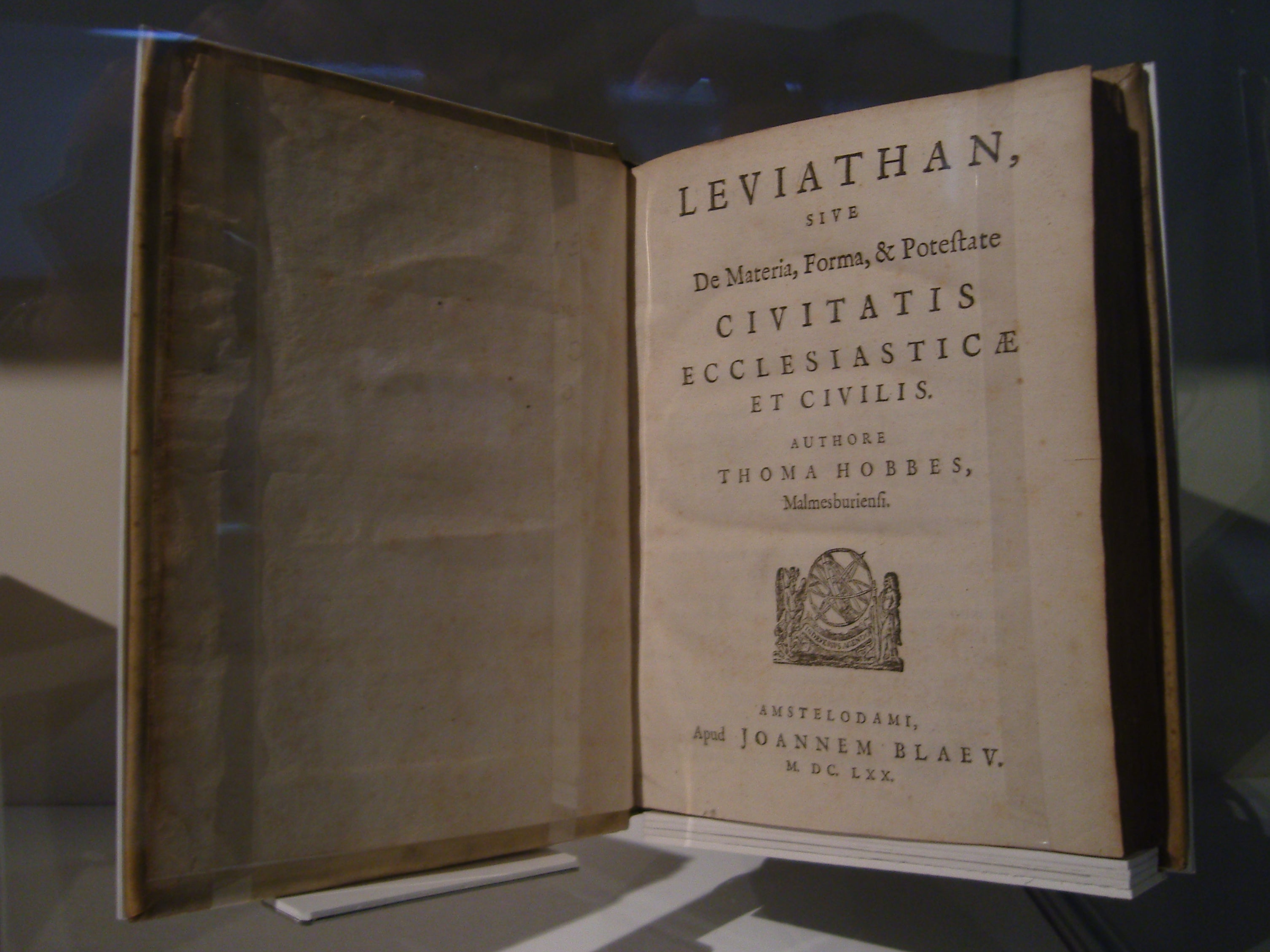

During his travels on the continent, he discovered geometry and Galilean views on motion, and he put both at the heart of his thinking. Great strides could be made, he argued, by adopting a method owed to the proofs of geometry, that is, by beginning with small things and simple truths. Further, facts about human desire and sensation as well as large-scale human activities could be understood in terms of the motion of smaller parts. Laws, not just of nature but of human nature, might be formulated. The bold culmination of Hobbes’s thinking in this connection is Leviathan, which was published just after the execution of Charles I. When Hobbes returned from France, the powers in London were debating matters central to the book. Hobbes had a clearly articulated and highly relevant position, and his work was widely read.

Leviathan

The book is perhaps most famous for seeking a justification of political obligation through reflection on what human life would be without it, and Hobbes’s conception of this state, the so-called “state of nature”, reflects a kind of deep pessimism concerning what it is to be human. The state of nature is characterised by both liberty and equality of a distinctly dark sort. Everyone in the state of nature has a share in absolute liberty, which seems to have two parts: it entails both the freedom to have anything a person can possess and keep as well as the freedom to do anything he can to preserve himself and what he has. A person has the right, then, to take any action “to preserve his life” and “do what he would … to possess, use and enjoy all that he would, or could get”. There is no such thing as a natural curb to human liberty, and Hobbes extends to the natural human even the right to kill. Further, everyone in the state of nature is also equal in power, in so far as anyone has the capacity to kill anyone else: even the weak can, quite literally, club together and collectively overcome the strong.

People in the state of nature become enemies as surely as physical objects obey certain laws of motion. Goods, comforts and resources are naturally limited or scarce, and so competition for them is intense. Equally intense is what Hobbes identifies as “natural diffidence”, which is the fear or insecurity that characterises natural human life – there can be no trust in the state of nature. The natural condition of human beings, that is to say, ungoverned human beings, is war, “every man against every man”. You would not enjoy life in the state of nature, but you could perhaps console yourself with the fact that your suffering would be short as you probably would not last very long. As Hobbes puts it, in the state of nature there is “no knowledge of the face of the earth; no account of time; no arts; no letters; no society; and which is worst of all, continual fear, and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short”.

The laws of nature

But you would want things to change. Perhaps the single, dim ray of light in this otherwise dark conception of what it is to be human are the three laws of nature that Hobbes identified. These laws of nature are dictates of reason, or conclusions one in the state of nature simply must draw. The first and most obvious law is that one must desire and seek the peace. Rationality, coupled with the fear of death, requires that people must wish to get themselves out of the state of nature, achieve better lives and some measure of security. Like a geometrical proof, the other laws follow on from this.

If one must seek the peace, one is then obliged to give up a share of one’s natural right, one’s liberty. Peace is not possible if everyone has an equal share in liberty, an equal right to everything and the means simply to take it. So Hobbes’s second law of nature is that everyone gives up this natural right and is “contented with so much liberty against other men, as he would allow other men against himself”. This consists in a mutual agreement among all those who seek protection, that is, a social contract, which in effect transfers absolute liberty from everyone to a single person (or group) who is then charged with using this power to keep the peace and ensure the security of all. As Hobbes puts it:

… it is as if every man should say to every other, “I authorise and give up my right of governing myself to this man or assembly of men, on this condition, that thou give up thy right to him, and authorise all his actions in like manner.”

Hobbes’s third law of nature is that people must keep their covenants. But this rational requirement might not be enough, Hobbes notes, as covenants “without the sword are but words”. To ensure safety from the horrors of our natural state, a serious sword is required, and Hobbes takes it that the power of the sovereign must be unqualified. The only sure way out of the state of nature is complete submission to a single, absolute power. The social contract, then, brings into being “that great LEVIATHAN, or rather, to speak more reverently … that mortal God, to which we owe under the immortal God, our peace and defence”.

It is worth noting an important fact about this set-up. It is the people themselves who contract together – the social contract is not entered into by the people on one hand and the ruler on the other. Instead, the people make a “free gift” of a part of their rights to the sovereign, and contract together to obey. Thus the king cannot in any sense break the contract, as he has not entered into it. However, reason demands that he avoid ingratitude, that he give the people no reason to “repent him of this gift”. He is therefore obliged to make their safety the highest law. This might seem to you, rightly, as a thin restraint on the king and a thin basis for your protection. It has seemed to monarchists a little worrying too. Exactly what might happen should the people repent him of this gift? If the power of the sovereign rests on the consent of the governed, might that consent be lost or taken away?

Criticisms of Hobbes

What seems to legitimise the absolute power of the government is the overwhelming desire to escape the state of nature. Hobbes’s twin brother, fear, is at the heart of things here. Hobbes claims that reason leads us to the laws of nature, but it is fear of death and general insecurity which really warrant handing over liberty. It is worth asking whether fear really can lead us to the contemplation of not just someone who stands a chance of ensuring the peace, but a supreme and unlimited power. You might join John Locke in wondering whether this sort of thing is a good idea, even a rational course of action, for the fearful masses. If you fear even your fellows, can that fear be reason enough to create something monumentally dangerous? As Locke asks, a little incredulously, “Are men so foolish that they take care to avoid what mischiefs may be done them by polecats or foxes, but are content, nay think it safety, to be devoured by lions?” Even if we follow Hobbes some way in his thinking about political obligation, it is not clear that we should follow him to absolutism.

For Hobbes, then, individual obedience to even an arbitrary government is necessary in order to forestall the greater evil of an endless state of war

But many have followed Hobbes, at least part of the way, maintaining that political obligation depends on some sort of consent, and social contract theory now has a long history of defenders. Some now take the contract to be implicit, adopting the old Socratic argument that enjoying the comforts and protection of the state is enough to oblige you to obey it, or in other words that it is as good as signing a contract. The philosopher John Rawls tells a story not about the state of nature, but the original position, from which he derives various principles of liberty and equality which are certainly not absolutist in nature. One wonders whether Hobbes himself might have found this annoying.

Major works

De Cive or On the Citizen (1642)

Perhaps the clearest and best articulated view of Hobbes’ moral and political philosophy, despite the greater fame of Leviathan.

This book develops Hobbes’s defence of the king’s right to rule as an absolute monarch, first developed in Elements of Law, Natural and Political (1640).

Leviathan (1651)

Hobbes’s philosophy undoubtedly finds its most complete expression in this work, his masterpiece of moral and political philosophy. The book begins with an avowedly materialistic account of human nature and knowledge, as well as a deterministic account of human volition and free will. Its most striking content, however, is the pessimistic vision of the natural state of human beings it provides.

Hobbes regards this natural state as perpetual struggle against one’s fellow man: it’s in order to escape this grim fate, Hobbes argues, that we form the commonwealth, surrendering our individual rights to the authority of an absolute sovereign, who in return will ensure our security and wellbeing. For Hobbes, then, individual obedience to even an arbitrary government is necessary in order to forestall the greater evil of an endless state of war. The alternative to this commonwealth, Hobbes famously said, is a human life that is “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short”. Leviathan also has an often neglected second half, which got Hobbes into trouble, concerning the philosophy of religion.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments