‘He is starving us’: Assad under pressure as Syria’s economy crashes

With the currency in free fall and food prices doubling, discontent is brewing across Syria, even within regime strongholds, as Bel Trew and Rajaai Bourhan report

In the beauty salons of the Syrian regime stronghold of Tartus, the wives of army officers quietly chatter about readying their fake identity cards and passports.

In case Syria and its battered economy completely collapse, they whisper to one another, they may have to flee at a moment’s notice.

Disillusion with the government of President Bashar al-Assad is running high in the seaside city.

“We used to love the president, and we were a strong supporter of al-Assad,” says Suzan, 31, who works at a salon and is a member of the Alawite Muslim sect which Mr Assad hails from. “He has protected us from the terrorists, but he is now starving us.”

Across the country, from regime territory to the rebel-held north, Syrians are barely surviving as the currency has tumbled and food prices have soared. Suzan, once an ardent government supporter, describes how an unprecedented financial crisis gripping the country has even hit the well-off in the Mediterranean city, largely spared the horrors of Syria’s nine-year civil war. There, residents fear the worst is yet to come. On Wednesday the US enforced its toughest sanctions yet on Syria, targeting 39 individuals and companies including, Mr Assad and his wife Asma.

Even before the restrictions bite, Suzan says in the poorer districts of the Alawite stronghold, the economic crisis had already translated into poverty, hunger and lawlessness. Just last week, Suzan’s own house was burgled.

“Theft is widespread, someone entered our house a couple of days ago, but he only stole food from the kitchen and left,” she tells The Independent. “Many types of medicines are unavailable.”

She said some people were planning protests against bad living conditions and behind closed doors, mounting anger was directed at the president himself.

“There is a limited amount of bread for each family, which is not enough anyway. People cannot cope.”

This week on the informal market the Syrian pound hit a record low of 3100 to the dollar, meaning since January alone it has lost two thirds of its value. Residents in opposition-controlled enclaves along the border with Turkey, told The Independent the crisis is so acute, locals have switched to using the Turkish lira to survive.

The World Food Programme says the price of a basket of basic goods has more than doubled over the last year – and is 16 times the cost of what it was in 2011 when the country’s civil war first erupted.

WFP’s director David Beasley even warned this week a “famine could very well be knocking on [Syria’s] door”.

The collapse of the currency also makes it difficult for the state to import food, adding to the bread shortages and higher prices. Over the last six months, an additional 1.4 million people have joined the ranks of the hungry in Syria, according to Daniella Moya, a spokesperson for UNOCHA in Syria.

Families are being pushed to the edge of survival

“More than 11 million need aid assistance, 90 per cent live below the poverty line,” she told The Independent. “Right now even more families – who have already been through so much - are being pushed to the edge of survival.”

The decade-long war in Syria has killed more than 380,000 people and displaced nearly half of the country’s pre-war population. Swathes of the country are still in rubble.

But with most of the fighting largely over, the toughest challenge ahead for Syria’s president may be handling crippling poverty and hunger.

This crisis has ravaged opposition areas on the front line like the northern province of Idlib, where the food price hikes are the highest. But it has also hit government strongholds, which over the last few weeks have witnessed murmurings of dissent.

The spiralling currency means the average government salary is now less than $16 a month. A kilo of sugar in Syria costs 2,000 Syrian pounds – the equivalent of nearly two days of pay.

As economic conditions worsen, demonstrations erupted in the southern city Sweida, the centre of Syria’s Druze religious minority which has enjoyed some autonomy over the last few years in exchange for its decision not to join the 2011 uprising.

Footage shared online showed protesters waving the Syrian revolutionary flag and calling for the overthrow of Mr Assad.

One man in regime-controlled Latakia, a centre of Mr Assad’s Alawite community, said he even saw people there criticising the president, and mocking the way he walks and talks, gestures that used to mean swift imprisonment.

“We (the Alawites) feel like we are between a rock and a hard place, we will not be safe if al-Assad loses power,” he told The Independent. “But people are devastated by the current situation and they know who they blame.”

Many said a repeat of the 2011 wave of revolt against Mr Assad remains unlikely. Damascus residents said they continued to fear criticising the president.

On Monday, the organisation Suwaida 24, an activist collective covering events in the city, reported Syrian security forces detained four demonstrators. A deal was reportedly struck that if protesters cancelled their rallies and stopped waving the revolutionary flag, all those in jail would be released.

It is the sign that the regime is clearly worried about public displays of dissent.

Just last week, Mr Assad himself dismissed the unpopular prime minister, Imad Khamis, in a move some believe was an attempt to deflect blame ahead of Washington’s sanctions. Many fear the US sanctions could exacerbate the economic misery.

There have been scant details about the Caesar Syria Civilian Protection Act – which Donald Trump signed in December and is named after the pseudonym of a Syrian military police defector who shared tens of thousands of photos of detainees tortured to death.

On Wednesday, US secretary of state Mike Pompeo announced designations against 39 individuals and companies for having played a key role in obstructing a peaceful political solution to the conflict. Singling out Asma al Assad, he said “many more” sanctions should be expected in the coming weeks and months.

It has piled extra pressure on the powder keg of Syria’s financial ruin, that was probably triggered by the Lebanese economic crisis next door.

The economies of Syria and Lebanon have long been intertwined but as the war has dragged on Syrians have increasingly banked in Beirut to keep their money safe and to circumnavigate existing sanctions.

Decades of systemic corruption and mismanagement finally saw Lebanon’s own economy crumble last autumn sparking the country’s own uprising.

Amid a crippling shortage of foreign currency, the Lebanese Central Bank has enforced punishing controls effectively locking both Lebanese and foreign customers out of their accounts.

Instead, account holders can withdraw their savings in the rapidly collapsing Lebanese lira, at terrible rates set by the banks.

This has panicked the most wealthy, according to Ribal Assad, Mr Assad’s maternal cousin and a member of a rival branch of the family, who is in touch with some of the richest echelons in Syria.

Ribal’s father Rifaat was sentenced to four years in prison in France on Wednesday for illegally using Syrian state funds to build a French real estate empire.

“Lebanon was the breathing space for Syria,” ”he told The Independent.

"Over $30bn worth of Syrian capital is locked up there but no one can take a penny out," he added.

Over $30 billion worth of Syrian capital is locked up in Lebanon but no one can take a penny out

The arrival of the coronavirus pandemic and global lockdowns have only worsened the situation. Remittances dried up as Syrians abroad were unable to send money home.

Domestic work within Syria, like daily labour, meanwhile, has all but stopped.

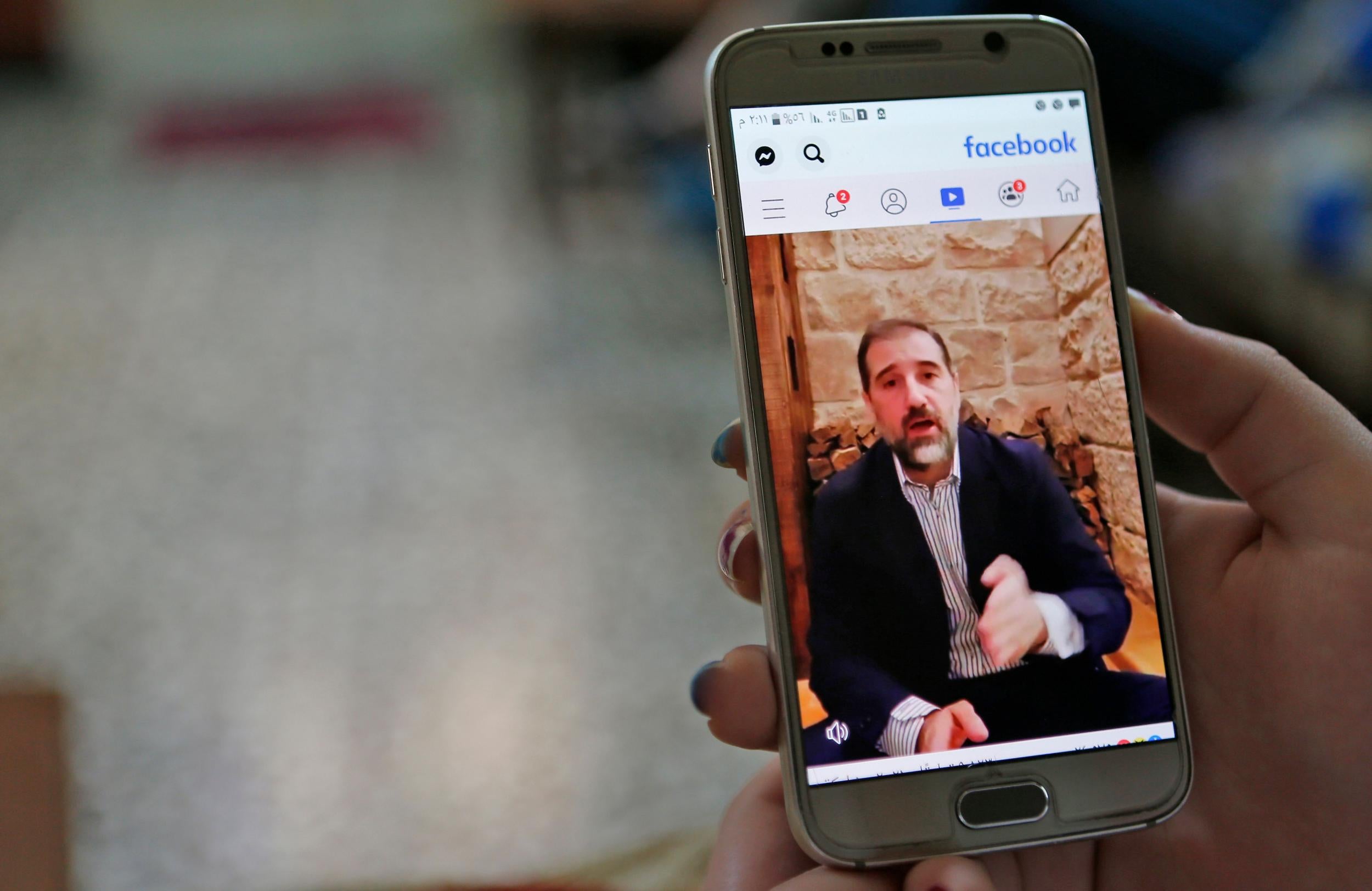

Further financial instability was triggered by an extraordinarily public spat between President Assad and his cousin, one-time billionaire Rami Makhlouf, who has posted several videos to Facebook complaining about his treatment.

Mr Makhlouf, the head of Syria’s largest mobile operator Syriatel, fell out with the regime over demands his firm pay $185m (£144m) in fines.

The regime stooge, who pre-war was believed to control over 60 per cent of the country’s economy, is now subject to a travel ban after his assets were seized.

He is one of several Syrian businessmen who have been targeted by the government in recent months.

It has worried many in Syria, who in a panic contributed to the economic distress by taking their much-needed money out of the economy and putting it under their mattresses, according to Elizabeth Turkov, a Syria expert at the Foreign Policy Research Institute.

“It raised concerns that if even the cronies were being targeted, people had better scurry away their money and convert it to dollars,” she said.

With foreign currency in scarce supply and the Syrian pound tanking, the government has tried some quick fixes including devaluing its currency by 44 per cent on Wednesday.

In the weeks before that, the authorities began arresting money changers who were not trading at the set rate and people caught using dollars. This so far has only backfired.

And so many like Danny Makki, a non-resident scholar at the Middle East Institute, believe “this is only the start of a downward spiral”.

He said while millions of the poorest will be impacted, sanctions may actually make the richest richer in a country where corruption is rampant. There are also fears as Syria struggles to import food due to its collapsing currency, the little resources available will be exclusively sent to areas deemed to be loyal to the regime.

“Western diplomats haven’t really thought about how the warlords are going to profiteer from this,” he said.

Civilians worry the new US restrictions will be the tipping point and halt any hopes of reconstruction in the country. They said they were “preparing themselves mentally” for the Caesar Act passing.

Panic is still mounting in the capital where locals describe internally displaced families sleeping in parks and streets.

“We can’t even price the goods because they keep rising,” says one young man who studied economics but works in an electronic store to feed his family.

Another said the regime will use the sanctions as an excuse.

“They will just blame the calamities in Syria on this,” he said.

“Quite literally, the situation is tragic.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments