Stargazing in December: Mars shines more brilliantly than any of the stars

Grab a telescope, if you can, to home in on our planetary neighbour any night this month, says Nigel Henbest

It’s bright, it’s red, and it’s high in the sky as we approach Christmas. No, I’m not talking about Rudolph’s nose as he leads Santa’s other reindeer. It’s the planet Mars, swinging by the Earth on 1 December, when it’s only 81 million kilometres away – the closest it’s been in more than two years.

Throughout the month, Mars shines more brilliantly than any of the stars, with its unmistakeable reddish glow. And we are in for a rare treat in the early morning of 8 December, when the full moon moves right in front of the Red Planet.

It’s surprisingly rare to observe the moon occult a planet: I’ve only seen it happen on a handful of occasions in my lifetime as an astronomer. And this occultation is highly unusual, in that it’s not just Mars, the moon and the Earth that are lined up, but the sun as well. The moon is opposite to the sun in our sky – the moment of full moon – at 4.08am on 8 December; and Mars is at opposition to the sun just 16 minutes later, at 4.24 am. (That’s a week after its closest approach, because Mars’s orbit is not circular but elliptical.)

As seen from the UK, the full moon moves in front of Mars at about 4.55 am, and it re-emerges at around 5.55 am. The exact times vary by a few minutes depending on your location, so start watching the event a bit beforehand. Although Mars is so brilliant, it may be difficult to see next to the moon’s brilliant disc, and binoculars or a small telescope will help. You’ll also notice that the Red Planet doesn’t just flick off and then on again. It takes time for the moon to move over the planet’s disc, so Mars appears to fade over a period of 30 seconds, and then take as long to brighten again.

Grab a telescope, if you can, to home in on our planetary neighbour any night this month, to see the Red Planet while it’s so close. Mars’s trademark red colour is down to the deserts that cover most of this small world, just half the size of the Earth. Darker markings on the planet’s globe change with the seasons, and astronomers once believed they were vegetation, but we now know these are regions of bare rock, whose appearance changes as seasonal winds blow the desert sands back and forth over them.

You’ll also spot the planet’s white polar caps. Though they look like the Earth’s arctic regions, in Mars’s chill climate it’s not water that freezes in the polar winters, but carbon dioxide from the planet’s atmosphere, snowing down as dry ice at -150C.

This small, cold world – wrapped only in a tenuous atmosphere – may not seem hospitable, but it’s the most likely place in the solar system to find living organisms that resemble life on Earth. A whole succession of space probes have flown past Mars, orbited the planet, landed on its deserts, and trundled across the surface in the quest to find out whether it was once a living world.

There’s certainly proof that this frozen world was once warmer, and boasted rivers, seas, and maybe even oceans of liquid water – the prerequisite for life. The sophisticated Perseverance rover (nicknamed “Percy”) has recently found evidence of organic molecules, the building blocks of living cells, within rocks at Jezero Crater. The rover is caching samples of these minerals, which will be returned to Earth by a future robotic mission. Once they are in a terrestrial lab, biologists will check whether the rocks contain any evidence of past life on Mars – or possibly even living cells, marking the first landing of alien life (albeit microscopic) on the Earth.

What’s up

December is limbering up to be an action-packed month for the planets. Topping the bill is Mars’s disappearing trick on the morning of 8 December, courtesy of the full moon, as I’ve previewed above.

The warm-up act comes a few days earlier, when the moon moves in front of distant Uranus on 5 December. The seventh planet disappears at around 4.50pm and reappears at about 5.20 pm; the exact time depends on your location. Uranus is so dim that you’ll need binoculars or a telescope to view this occultation, but it’s worth the effort just to add Uranus to the tally of planets you’ve seen for yourself.

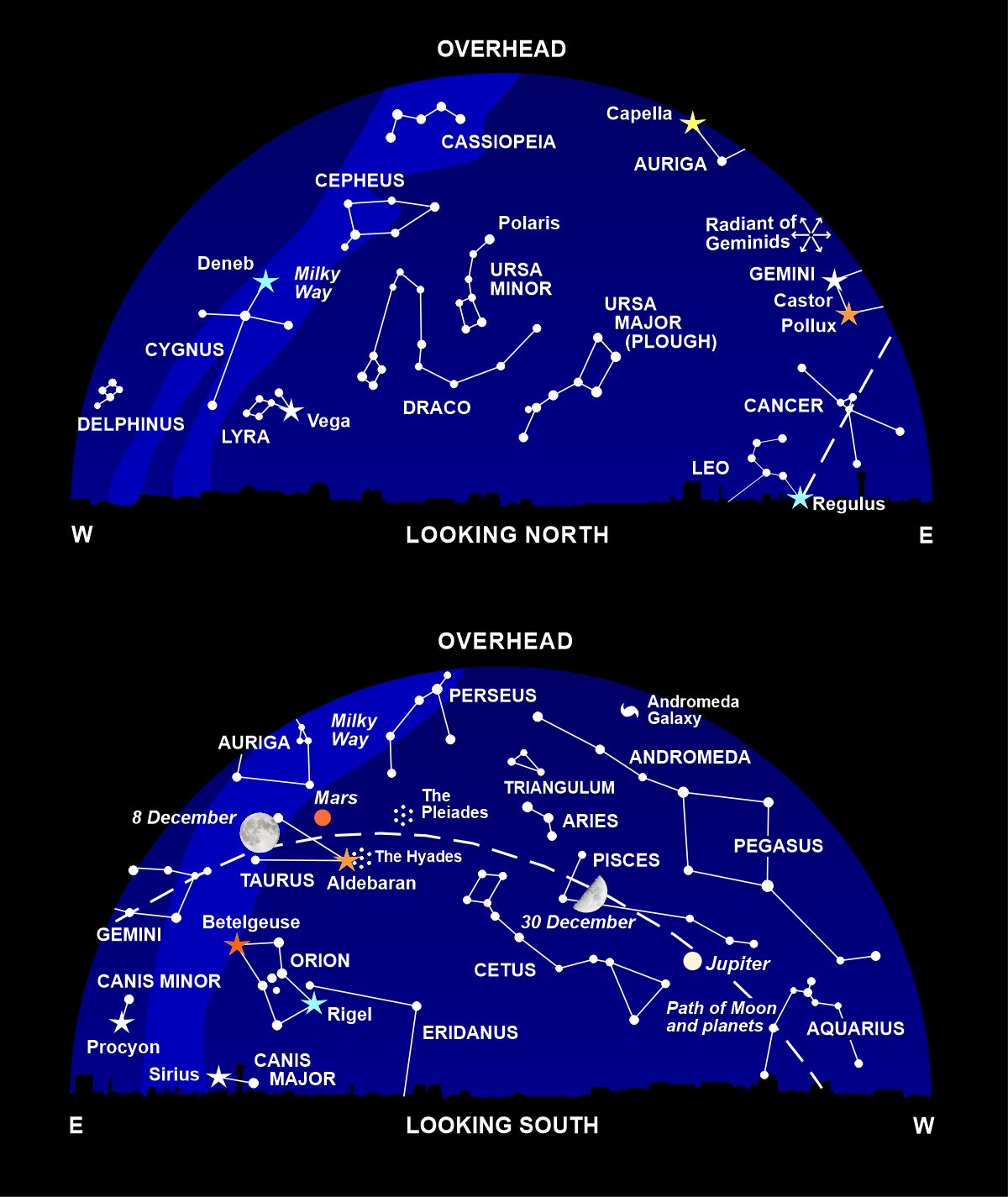

On the easy list of planets to spot, alongside Mars is giant Jupiter, which dominates the evening sky over to the southwest. To its lower right, you can find the solar system’s second-largest world, Saturn, now setting at around 8pm. Right at the end of December, brilliant Venus appears low on the southwestern horizon, well to the lower right of Saturn; with binoculars, you’ll find little Mercury hanging above it. And look down between your feet for one more planet you can add!

Back in the sky, we’ll be treated to one of the year’s best displays of shooting stars on the night of 13-14 December, though bright moonlight will take the edge off the show. The Geminids are fragments of the asteroid Phaethon burning up high above our heads. These particles are larger than the comet dust that causes most of the other meteor showers, so the Geminids are brighter than the average shooting star.

And let’s not forget the brilliant winter constellations now well in view. Mars lies amid the stars of Taurus (the bull), with the familiar humanoid shape of Orion below and the twin stars of Gemini, Castor and Pollux, to the left. Below Orion blazes the Dog Star, Sirius, the brightest star in the night sky.

Diary

1 December: Mars closest to Earth; moon near Jupiter

5 December: moon occults Uranus

6 December: moon near the Pleiades

7 December: moon near Mars and Aldebaran

8 December, 4.08 am: full moon; Mars at opposition; moon occults Mars

10 December: moon near Castor and Pollux

11 December: moon near Castor and Pollux

13 December: maximum of Geminid meteor shower

16 December, 8.56 am: last quarter moon

21 December, 9.48 pm: winter solstice; Mercury at greatest elongation east

23 December, 10.17 am: new moon

25 December: moon near Venus and Mercury

26 December: moon near Saturn

29 December: moon near Jupiter

30 December, 1.20 am: first quarter moon

Nigel Henbest’s latest book, ‘Stargazing 2023’ (Philip’s £6.99), is your monthly guide to everything that’s happening in the night sky next year

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments