Football in fear? What Luis Diaz’s family kidnap ordeal means for the beautiful game

The staggering sums of money swilling around the modern game are like targets on the backs of its biggest stars, writes Miguel Delaney. Robberies and kidnappings – often at gunpoint – have become such a threat that teams and players are now taking special precautions, including social media bans, minders and guard dogs

It was a few hours before what should have been a fairly routine Europa League match against Toulouse, and the Liverpool squad were relaxing and conserving energy in their usual pre-match venue of the city’s Titanic Hotel.

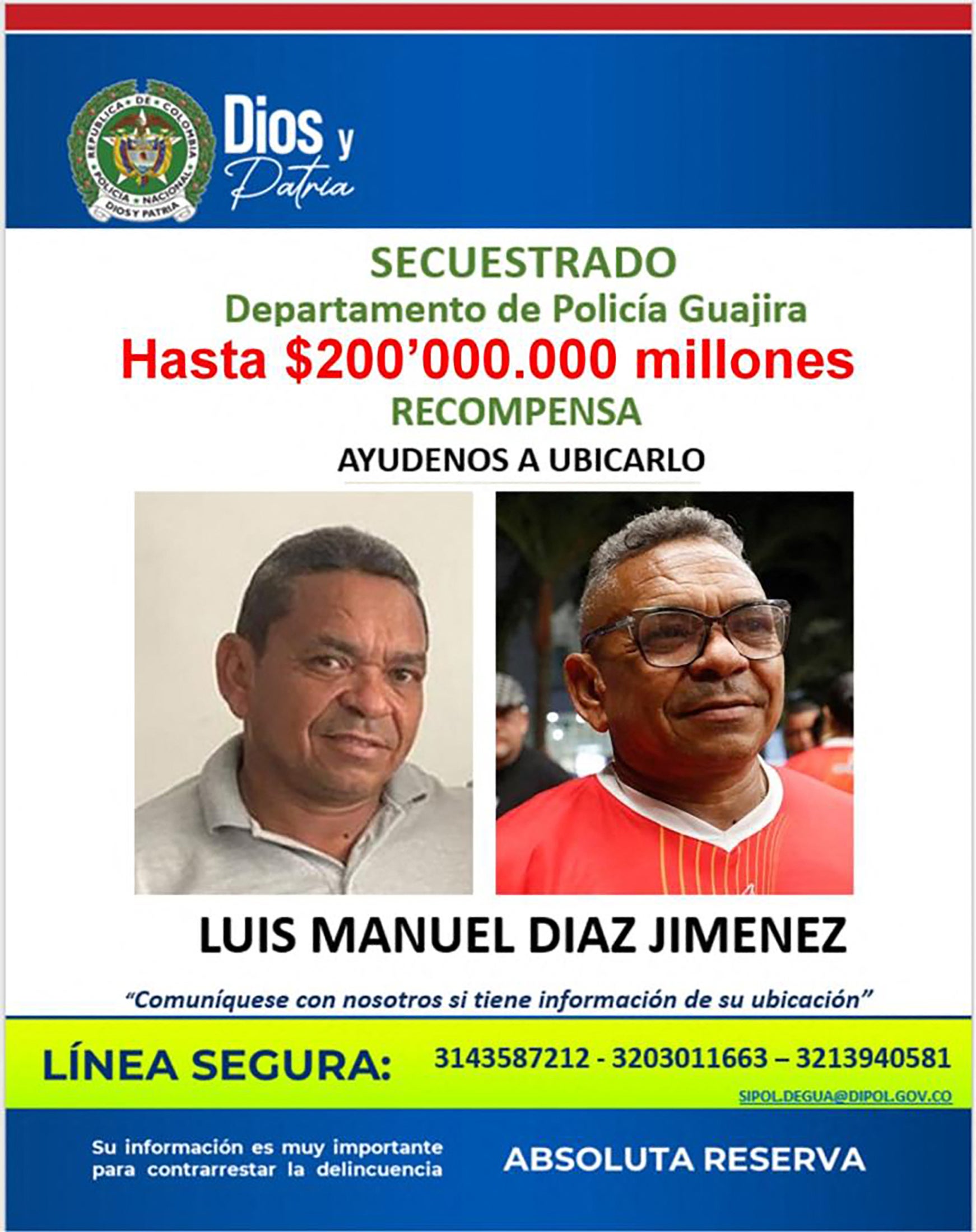

The mood soon shifted as the talented and popular left-winger Luis Diaz was called away in serious, hushed tones, and the rest of the players were given the shocking news: the Colombian star’s parents – Cilenis Marulanda and Luis Manuel Diaz – had been abducted in his home country, after being stopped by gunmen on motorbikes.

Diaz, naturally, flew straight back home, where his mother was soon rescued by a police operation in the city of Barrancas. His father remains in captivity, as a guerilla group called “Ejercito de Liberacion Nacional” (ELN) claimed responsibility. They had been in peace talks with the Colombian government.

The Diaz family has been given full support and shielded from any media scrutiny as they try to get through this situation back home, but Colombia president Gustavo Petro did offer comment on social media: “In an operation in Barrancas, Luis Diaz’s mother has been rescued, we continue the search for the father.”

The Liverpool squad are understandably deeply concerned for a teammate and many have “found it difficult to get their heads around” – that something as grave as this could happen so suddenly. Manager Jurgen Klopp described dealing with it all as “a new experience I never needed.”

The reaction in Diaz’s home country has been even more complicated and confusing. This is the sort of dreadful event that just doesn’t happen in modern Colombia, but it was an instant and painful reminder of the past.

The depressing days of narcoterrorism in the 1980s and 1990s involved thousands of kidnappings, and the intersection with the national sport inevitably saw footballers targeted. The notorious 1994 World Cup campaign in the USA brought threats to midfielder Gabriel Gomez, and the stifling pressure felt by the squad contributed to a disappointing first-round exit. The fall-out brought the most tragic episode in Colombian football history when Andres Escobar was murdered on a night out after the squad’s return.

Traumatic incidents like this and the Diaz case should not foster the feeling that this only happens far away from the hermetically sealed shine of the Premier League and the wealth of Western European football. That is sadly not the case. One reason his parents’ kidnapping so shook Diaz’s Liverpool teammates was the realisation something similar could very easily happen in their own English homes, never mind just close to home.

Many of the current Liverpool squad played with Senegalese star Sadio Mane and Brazil’s Roberto Firmino, who both had their houses in the North West on England burgled. Firmino’s, in Liverpool suburb Mossley Hill, was raided by a hooded gang in 2017, although mercifully his wife and child were not home at the time.

A decade before that, in 2007, Steven Gerrard’s wife Alex was confronted by a gang who told her to empty the contents of her safe or they would “take her kids”. In July of this year the Paris Saint-Germain (PSG) and Italian goalkeeper Gianluigi Donnarumma was tied up in his flat with partner Alessia Elefante by what French police described as an “organised gang.” Elefante was unharmed and Donnarumma suffered light injuries, but their captors made off with around £430,000 worth of possessions.

That was only the most severe of many similar cases involving PSG players over the past few years, and this at one of the world’s wealthiest clubs, operating in one of its richest cities.

What the horror of Diaz’s case really highlights is how the global popularity and wealth of football has made players targets to a far greater degree than ever before. It has become a growing problem for clubs in a way that used to be largely a primary concern of the super-rich in business, fashion and other walks of life.

That was always the raison d’etre of this type of crime. It was about gangs assessing the value of the victim or – worse for them – the price put on their families. It is telling that many cases have come in the wake of high-profile transfers.

While the super wealth of footballers is a relatively recent development, their very prestige and popularity always made them targets. Take two fabled players, considered the greatest of all time, and undeniably the greatest of their eras. As far back as 1963, Real Madrid legend Alfredo Di Stefano was targeted when the Spanish club was on a tour of Venezuela, in a case that has some echoes of that of Diaz’s parents.

The then 37-year-old, who at that point was the defining star of Madrid’s first five European Cup wins, had decided to have a night in as teammates went out in Caracas. Di Stefano was awoken at 6am by a group claiming to be anti-narcotics police. They were actually the Armed Forces of National Liberation (FALN), a left-wing group seeking attention for their campaign against the authoritarian government of Romulo Betancourt.

“We do not have anything against you,” Di Stefano was told by one of his captors. “We are doing this only so the press pays us attention. The government forbids the newspapers to talk about the FALN. You are going to stay with us a few hours, and then we will bring you back. We do not want to hurt you.”

Extraordinarily, the group had actually thought about abducting Russian composer Igor Stravinsky initially but feared his ill health at 81 years of age could cause death due to stress, as well as blood on their hands, neither of which they wanted.

Di Stefano was still unable to relax while in captivity despite such reassurances, later admitting he constantly feared assassination. The group’s leader Maximo Canales sought to calm him by playing chess and releasing a photo of them together to the media. FALN got what they really wanted though: three days of headlines, after which the leadership gave the order for Di Stefano to be released. He sprinted to the Spanish embassy.

Fourteen years later, and shortly before the 1978 World Cup in Argentina, a player considered Di Stefano’s natural successor suffered an even worse ordeal. Johan Cruyff had a group of criminals enter his house in Barcelona and tie him and his family up at gunpoint.

While the Dutch star managed to escape, he admitted it changed his perspective on life. Cruyff later revealed the ordeal was the reason behind the mystery of why he didn’t play at the 1978 World Cup when the Netherlands were the favourites. They lost 3-1 after extra time in the final to the hosts.

“The children were going to school accompanied by the police,” Cruyff told Catalunya Radio. “The police slept in our house for three or four months. I was going to matches with a bodyguard. All these things change your point of view towards many things. There are moments in life in which there are other values. We wanted to stop this and be a little more sensible. It was the moment to leave football and I couldn’t play in the World Cup after this.”

If such security concerns were unusual at the time, and still somewhat extreme, they are now part of the everyday planning of major clubs. It has inevitably escalated in areas of greater economic and social inequality. So, just as narcoterrorism has migrated with the cocaine trade from Colombia to Mexico, so has the threat of kidnapping.

It says much about the issue that one figure with direct knowledge of such ordeals does not want to speak to The Independent about it or even give details because “it is not something people like to put a face on – this is a very live worry for footballers.” While ransom and extortion are usually the main motivations, it can also be as simple as players or their families and entourages irritating the wrong people from the wrong group on nights out.

It has even created situations people in the game could scarcely believe. One source who worked in Mexican football tells the story of a kidnapped manager whose club sought to temporarily replace him, only for the new manager to do so well the poor abductee found he didn’t have a job when he was released.

Modern clubs take concerns much more seriously. Security details have been greatly increased and usually involve ex-military personnel. One high-profile England player has a former marine who is constantly in his sphere, but “you wouldn’t know he’s there”.

Back at home, there are now specialist businesses that sell specific breeds of dogs to players for home security. The Rottweilers cost £15,000 and take a year to train. Raheem Sterling is the most famous to have bought one, naming his Okan.

Other tactics have crept into the everyday life of players. Some squads are told to always delay social media posts so as not to signal to millions of followers where they are. That is naturally quite difficult when commercial deals require them to attend events and post about it.

A further complication, however, is one of the core aspects of the job. The fixture calendar list is like a giant public neon advertisement for where every player is likely to be on any given day of the year, which has been a key reason for a spate of robberies during major European competitions.

Beyond Liverpool, some of the Premier League’s most high-profile players have become victims when their absence on club duty was widely known. Sterling’s home was infamously raided during the World Cup last year, forcing his temporary return to England. Frank Lampard had his house broken into four times. The mother of former Manchester City player Robinho was kidnapped in Sao Paulo in 2004, although later released.

Diaz’s mother is thankfully free now, too. The advanced Colombian military is currently searching for his father. The entire case is seen by those close to the situation as the extreme end of all these examples, a tragic consequence of specific circumstances such as his status and the fact Diaz comes from one of the most underprivileged areas of the country, La Guajira, just north of the Venezuelan border.

“The best thing we could do for our brother was that we win the game and distract him a little bit maybe,” Liverpool manager Klopp said following the team’s victory over Nottingham Forest. “After more than 1,000 games you would think you have experienced everything, but no.

“But it’s not about us, it’s about ‘Lucho’ and his family, and we all pray and hope that everything will be fine. What we can do, we will do, we’ve done already in the club and the only thing we could do today was fight for their brother – and that’s what they did.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks