Deadline looms for Spanish public to cash in pesetas for euros

Spanish citizens have until Wednesday to swap the peseta for euros or they will be left with worthless pieces of paper, writes Graham Keeley

To many people of a certain age, the peseta is evocative of holidays in Spain when bundles of this exotic currency might buy a round of sangria or a paella.

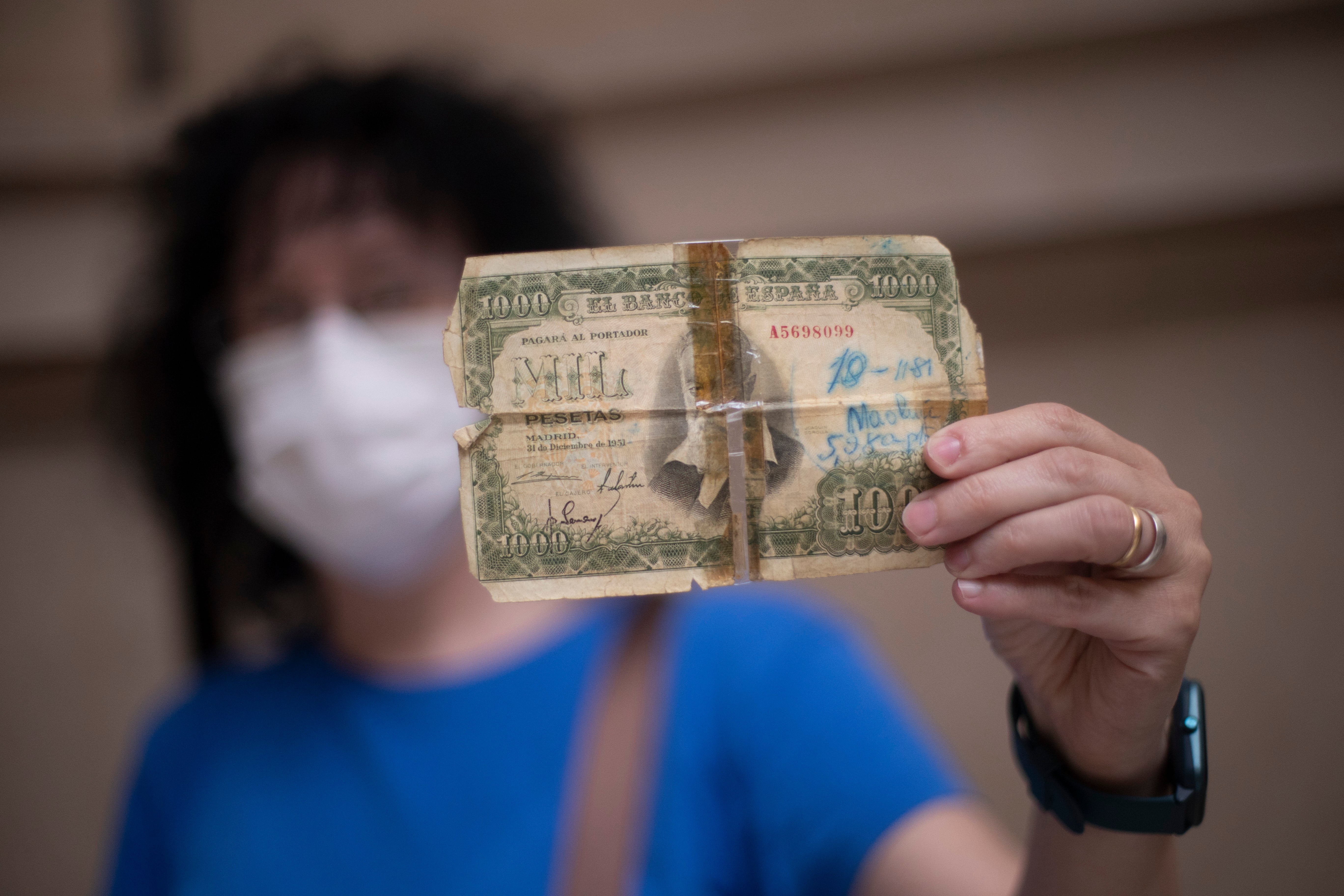

However, for Spaniards who may have guarded bundles of the out-of-date currency under their mattresses or stuffed into suitcases, it’s time to cash in these hidden fortunes: they have until Wednesday to swap the peseta for euros or they will be left with worthless pieces of paper.

The Bank of Spain estimates that there are €1.5bn ( £1.28bn) worth of pesetas in circulation, stashed away in forgotten bank vaults or discarded envelopes.

As the deadline approaches, long queues have formed outside branches of the Bank of Spain, with many anxious to make a quick killing out of this relic of the country’s past.

“It’s typical of some Spaniards to leave everything to the last minute,” said Jose Maria Garcia, who used a shopping trip to Zaragoza in eastern Spain, to cash in pesetas he had kept stashed at home for nearly 20 years.

He waited over an hour in the queue to cash in pesetas worth only €140 but said it was worth the wait.

“I will buy my granddaughter presents for passing her examinations,” he said.

By chance, Rosario Perez came across an envelope with some old pesetas inside so she decided to cash it in at the bank – even if it entailed a long wait.

“I have had to wait nearly over three hours. I think the pesetas are only worth about €40 but I wanted to cash it in anyway. This just teaches you not to leave things to the last minute,” she said.

Helena Tejero, director of the cash desk at the Bank of Spain, said customers were arriving with complete suitcases or packets full of notes.

“The other day I spent an hour breaking open plastic bags in which a woman brought the money. It was a long day,” she told El Independiente newspaper.

The bank has been exchanging pesetas for euros for the past 18 years but has said the process will now end.

At today’s rate one euro – equivalent to 86p – is worth 166,386 pesetas.

The peseta went out of circulation in 2002 when Spain joined the eurozone, consigning to history the currency which it had used for over 150 years.

Suddenly these red, green or blue notes with images of the late dictator General Francisco Franco or the former king Juan Carlos were no more.

The peseta first came into circulation in 1868 when it replaced the peso and Spain considered joining the Latin Monetary Union system.

Notes going back to 1939 – when the Spanish Civil War ended – are acceptable at bank branches across the country.

“Pesetas produced between 1936-1939 during the Spanish civil war may also be accepted at the bank but it depends on their condition,” said a Bank of Spain spokesman.

The currency may not have been around for nearly 20 years but it is part of Spanish folklore.

The peseta, despite being a symbol of Spain, owes its name to a Catalan word pesseta which means small piece of currency.

During the Spanish civil war between 1936-1939, the Republican government had to use thin strips of cardboard to make the peseta banknotes because paper was in such short supply.

While Spain remained neutral during the Second World War, the country which had been ravaged by a bitter civil war virtually stopped making coins because metal was in such scarce supply.

One and two peseta notes were made from paper instead.

Counterfeiters were so rife during the 20th century that the Bank of Spain contracted foreign companies to produce pesetas because it could not trust the Spanish bank note makers.

Brown 5,000 pesetas notes came into circulation after the restoration of democracy in 1975 when Franco died.

These notes may not be possible to exchange at the Bank of Spain but they can still be sold on the specialist markets. Their value will depend on how well they are preserved or the rarity of the note

Apart from Queen Isabel of Spain, the poetess Rosalia de Castro was among the few women to appear on the notes.

When democracy was restored 1975 after the death of General Franco, the first coins which bore the profile of the new king Juan Carlos showed the monarch looking to the left – a move which was opposed by right-wing parties at the time.

Jesus Vico, president of the Spanish Association of Professional Numismatists, professionals who deal with coins, said the value of rate notes from the civil war years will depend on their condition.

Bank experts will analyse these notes to see if they are acceptable.

“These notes may not be possible to exchange at the Bank of Spain but they can still be sold on the specialist markets. Their value will depend on how well they are preserved or the rarity of the note,” he told The Independent.

Mr Vico said some rare notes will be worth thousands of pounds like the first peseta note which was made in 1874.

Another sought after note is the 1,000 peseta which entered circulation in 1892 and can be worth up to €30,000 (£25,788).

The 1,000 peseta note from 1895 with the image of the painter Francisco de Goya is valued at between €15,000 (£12,894) and €20,000 and (£17,192).

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks