Books of the Month: From Sinead O’Connor’s Rememberings to Lisa Taddeo’s Animal

Martin Chilton reviews six of June’s biggest releases for our monthly column

Sinéad O’Connor’s fearless autobiography Rememberings is a riveting account of modern celebrity and a deeply candid account of her own “trainwreck” life. The singer’s memoir also addresses the grim truths of sex and power in the modern world – a subject close to the heart of Lisa Taddeo, whose 2019 non-fiction bestseller Three Women explored female sexuality and desire. Her debut novel Animal, like O’Connor’s book, has important things to say about the mistreatment of women in a male-dominated society.

The final instalment of the second Fifty Shades trilogy, which ties up the story of Christian Grey and his soon-to-be bride Anastasia Steele, is also out in June. “And I do it again. And again,” boasts Christian, while in the midst of “thrusting” Ana, early in the opening chapter of Freed: Fifty Shades Freed as told by Christian. “Again and again” seems to sum up the public’s unending desire to lap up the same steamy slop from author EL James.

Joanna Walsh, described as a “multidisciplinary writer for print, digital and performance”, captures the fragile experience of growing up in her hypnotic, challenging novel Seed (No Alibis Press). The 1980s protagonist, just turning 18, is trying to make sense of coming out in a world of Aids, nuclear anxiety, and her own battles to make sense of fractured sexual politics (“I am a feminist/I don’t like any of the women here”). The novel, written in layers of poetic prose, is hard to define, but it is lush, experimental and strangely lovely.

Caring for an elderly parent is like being sucked into a “whirlpool of limitless need”, in the words of Kay Wilkinson, one of the central characters in Lionel Shriver’s new novel Should We Stay or Should We Go. Shriver, the author of We Need to Talk About Kevin, has constructed an adventurous novel involving 12 parallel universes for Kay and her husband Cyril after they turn 80 – the age at which they originally promised to end it all together.

“Care is a feminist issue,” according to novelist Kate Mosse, as she reflects on the gender disparity involved in looking after the long-term sick and elderly in An Extra Pair of Hands: A Story of Caring, Ageing & Everyday Acts of Love (Profile & Wellcome Collection). There are now 8.8 million adults in the UK who are carers, and by the age of 59, women have a “50-50 chance of being a carer”. Men don’t have equivalent odds until they are 75. Although Mosse makes telling social observations in this non-fiction book, it is, at heart, a moving, delicate portrait of her own time as a carer for her parents, including her Parkinson’s-ravaged father. Having been through the same mill, I can honestly say that Mosse captures the experience, and the sense of powerlessness and heartbreak, with skill and tender precision.

Ian Robertson’s How Confidence Works: The New Science of Self-Belief, Why Some People Learn it and Others Don’t (Bantam Press) is another new non-fiction publication that focuses on the continuing problems of sexism and gender inequalities. Robertson, co-director of the Global Brain Health Institute, details how girls aged between eight to 14 drop in self-confidence, systematically underestimating their knowledge and abilities compared to boys. In an international survey of educational achievements, “male students bullshitted much more than females”, across all nine English-speaking countries in the survey. “Wealthier children also bullshitted more than poorer children,” he reports. The young men were confidently able to boast about a deep knowledge of 16 different mathematical concepts, even though three of them were completely fabricated terms.

Poet Walt Whitman said he detected a “deep latent sadness” in Abraham Lincoln’s eyes. An explanation for the President’s melancholy comes in Michael Burlingame’s An American Marriage: The Untold Story of Abraham Lincoln and Mary Todd (Pegasus Books), a startling history book. Lincoln expert Burlingame reportedly spent 30 years researching this account of Lincoln’s terrible relationship with his wife, who is now believed to have been bipolar. The First Lady, who accepted bribes for pardons, often physically abused her husband (surprisingly, since she was 5ft 2in and he 6ft 4in). She also attacked White House staff. In one incident she ripped a pierced earring from a young Norwegian servant called Hannah Knudson, “tearing her earlobe”.

O’Connor’s Rememberings, along with David Storey’s memoir, and novels from Taddeo, CJ Carey, and David Peace, and short stories from Elizabeth McCracken are reviewed in full below.

Rememberings by Sinéad O’Connor ★★★★☆

“I have been angry at my mother all my life,” admits Sinéad O’Connor in her candid, quirky autobiography, Rememberings. It’s not hard to understand why she was furious. The Irish singer, born in Glenageary on 8 December 1966, was subjected to horrific violence from her Valium-addicted mother Marie. She made O’Connor repeat the words “I am nothing”, before forcing her daughter to strip naked, open her legs and wait for an assault. “She hit me with the sweeping brush in my private parts,” O’Connor recalls.

After a broken childhood – truancy and shoplifting led to a spell in a Magdalene asylum – O’Connor made it as a musician. The memoir offers a frank insight into her turbulent life as a young female celebrity, desperately trying to be “financially independent of people with penises”. Perhaps the weirdest of all the book’s anecdotes is the account of her deranged meeting with Prince – who wrote her best-selling hit “Nothing Compares 2 U”: his threats to “kick the shit” out of her and his sinister attack on her with a weighted pillow. It says everything about her spirit that she was able afterwards to refer to him dismissively as “Ol Fluffy Cuffs”.

Rememberings sparkles with O’Connor’s acerbic wit and she is funny about her own mishaps in what she calls a “trainwreck” of a life. She jokes about making an album with her brother Joe and naming it F*** the Corrs; when describing the best-selling 1972 illustrated sex manual The Joy of Sex, she mocks the two off-putting drawn models. “The two of them are really ugly. He has a horrible beard. They put me off the whole idea of sex,” she says. She recounts losing her virginity at 14 and is open about her many adventures in bed along the way, including with the four different fathers of her quartet of children. She was often exploited, including by a married church minister in London, and offers a withering aside about Peter Gabriel, whom she claims she left because, “I got fed up with being weekend pussy”.

O’Connor has a lot of meaty subjects to cover in describing a career that has never been far from controversy. Her most newsworthy exploits include the famous cropped hair revamp (a shaved head which earned her a kicking from a bouncer in Liverpool) and the time she notoriously tore up a photograph of Pope John Paul II live on television, earning a life ban from NBC. “This hurts me a lot less than rapes hurt those Irish children”, she remarks, referring to the Catholic Church’s record of covering up sexual abuse cases.

O’Connor is a courageous autobiographer, something evident in the honest account of her own drug-taking, her breakdown, and her suicidal impulses after a hysterectomy in 2015. She is disarmingly open about her own painful mental health problems. Although the stream-of-consciousness style of the writing allows for a confessional openness, there are times when the scattergun nature of the reminiscences results in interesting subjects popping up and disappearing without being covered in sufficient depth; for example, her stage fright, how exactly she was “bullied and spiked” at a party at Eddie Murphy’s house, her conversion to Islam, and her rebirthing.

As for the future, the singer says she wants to retrain as a healthcare assistant and continue making music. This is good news, because the genuine nature of her love of music shines through the book, revealed often in small, telling details. The most affecting reflection, for me, was her admiration for a fabulous Irish instrumental called “The Lonesome Boatman”. The tune, composed by Finbar Furey when he was 12, is described by O’Connor as “the most beautiful and haunting melody I’ve ever heard. Such grief to have come from a child”.

O’Connor’s own past was harrowing and she is certainly well placed to judge what is haunting. Her strikingly honest memoir is the work of a born survivor.

‘Rememberings’ by Sinéad O’Connor is published by Sandycove on 1 June, £20

A Stinging Delight: A Memoir by David Storey ★★★★☆

When middle-aged novelist and playwright David Storey attended the psychiatric department of his local London hospital, the acclaimed author of This Sporting Life and the Booker Prize-winning Saville, was asked by an analyst to describe his view of life? “Despairing,” was his succinct, doleful reply.

There is plenty of misery and melancholy in Storey’s deeply moving posthumous memoir A Stinging Delight, published four years after his death at the age of 83 in 2017. But there are also bags of wonderful humour, eccentricity and wisdom.

Some of the best moments deal with his raw upbringing in Wakefield, West Yorkshire. His father was a coal miner, and much of the autobiography is addressed to his eldest brother Neville, who died, aged six, while their traumatised, suicidal mother Lily was pregnant with the future writer. Storey is convinced the impact of this on his mother laid the ground for his own paralysing mental health problems. “I had the mental equivalent of brittle bone disease,” writes Storey. “Not only fear, but the fear of fear; not only terror but a terror of terror, fiercer than the original source.”

There are eye-opening accounts of the dating landscape of post-war England; one girl’s mother stalks them, appearing out of the darkness to hiss at her daughter, “Do you wish to be turned into a prostitute?”; and beautifully written, wry descriptions of his time playing professional sport for Leeds Rugby League Club and working for the West Riding Bus Company. The tale of his long-running feud with younger brother Tony is surreal; the warped nature of their antagonism is hard to understand from the outside. Meanwhile Storey’s wife Barbara is a somewhat anonymous figure in the book. Then again, this really is only a tale of Storey’s own tortured mind.

Storey was desperate to escape what he calls “the philistinism of provincial life” and the book details his life in London. After a controversial time at the Slade School of Art, Storey taught in 17 rough inner-city schools and he brings to life the full oddity of that experience. He overheard one headmaster refer to him as “this spiv who’s just arrived”. His accounts of ordinary working life are, if anything, more enlightening than his accounts of mixing with celebrities, as he made it in the world of stage and film.

Storey had his own original way of dealing with critics who gave him bad reviews. When he spotted a group of arts writers in the coffee bar of London’s Royal Court theatre, he sought out the ones who’d lambasted his play Mother’s Day. Poor old Philip French, Irving Wardle and Michael Billington were given “half a dozen cuffs on the back of the head”. Billington later admitted the blows were “quite painful”.

A Stinging Delight is an engrossing memoir. One warning, though. As a young boy scout, Storey witnessed a horrific road accident near York, in which a young boy was brutally killed. It is one of the most disturbing, harrowing descriptions of parental anguish I’ve ever read. Storey certainly had a way with words.

‘A Stinging Delight: A Memoir’ by David Storey is published by Faber on 3 June, £20

The Souvenir Museum by Elizabeth McCracken ★★★★☆

The quicksand of love and family relationships is one of the themes of Elizabeth McCracken’s marvellous collection of short stories The Souvenir Museum.

McCracken, a former librarian and National Book Award finalist who teaches at the University of Texas, has a gift for startlingly original turns of phrases and piercing observational writing. She refers to “a lobby filled with departing hangovers and their owners”, to a man with a cactus soul (“it needed water, too, but it could wait”), to a man who is the emotional “load-bearing wall” of a family, and to a septuagenarian English couple wearing matching shoes “that looked like baked potatoes”.

The 12 stories are varied and imaginative. They include the sinister tale of a grieving mother who compulsively feeds on loaves of challah, the peculiar account of a recent widower and his adult son on a trip to a Scottish isle in search of puffins, and the tale of a ventriloquist and her young lover.

There are several stories about an American couple called Jack and Sadie. We encounter them first in the story The Irish Wedding, when Sadie is meeting Jack’s strange family for the first time. “Together Jack and his sisters looked like the full toolbox: hatchet, knife, spade, trowel,” she notes. The Irish Wedding is bittersweet and funny and has a hilariously happy ending. McCracken concludes the book with them, years on in their journey, in the closing story Nothing Darling, Only Darling Darling, when they have just argued bitterly during a trip to Amsterdam. Jack has a temper tantrum and locks Sadie inside a canal boat, “to punish her for being insufficiently interested in Anne Frank”.

McCracken has a real talent for exploring what makes an individual unusual when they are entwined with another person, and her stories are sparkling gems of human eccentricity.

‘The Souvenir Museum’ by Elizabeth McCracken is published by Jonathan Cape on 3 June, £14.99

Widowland by CJ Carey ★★★★☆

In the 1953 Nazi-ruled Britain imagined in the feminist dystopian novel Widowland, there is nothing lower than a woman “who did not serve a man”.

Rose Ransom, the blonde, blue-eyed 29-year-old protagonist of the novel – written by Jane Thynne under the pen name CJ Carey – is a “Geli”, the most elite of the caste system imposed after German occupation. She is taken away from her usual job of censoring fiction to go undercover and unearth the mysterious insurrectionists from the Widowland district; the slums where childless women over 50 have been sent. These middle-aged women are threatening the regime ahead of the Leader’s arrival in London to attend the Coronation ceremony of King Edward and Queen Wallis.

In this alternative history, neatly established by Thynne, the prime minister is Oswald Mosley – Winston Churchill has been sacked and branded a “traitor”; George VI has been arrested and deposed; Princess Elizabeth is banished, and Rudolf Hess and Joseph Goebbels are flourishing.

Although the setting is fictional, the story is based on the SS task force Alfred Rosenberg set up to loot European libraries on behalf of Hitler. Rosenberg’s book-burning campaigns – and his plans to adjust history books to reflect Nazi beliefs about the past – are cleverly skewered in the scenes in which it is explained to Rose why books are “every bit as dangerous as bombs”. The outlawed “degenerate”, subversive female authors of the past – including Mary Wollstonecraft, Charlotte Brontë, and Jane Austen – are the unspoken heroines because their words are the literary fuel that ignites the rebellion against the women-oppressing occupiers.

Rose’s boss and lover, a creepy SS commander called Martin Kreuz, particularly hates Pride and Prejudice because “it teaches that marriage can subject women to degradation”. Widowland certainly offers a dystopian nightmare scenario, featuring Gove-like, sorry Rosenberg-like, plans to “adjust” how the past is presented and to tell “History with a capital H”, whitewashing past transgressions. In Widowland, there are also references to the level of violence towards women committed by those who feel “emasculated by their position in the hierarchy”. The lines between 1953 and 2021 are certainly blurred.

Rose is infected by the spirit of Widowland and gradually starts to question everything about a world of castes and detention camps, particularly when she learns of secret plans to wipe out people with disabilities and mental illnesses. There is a droll moment when Rose, who is in the process of producing a sanitised edit of Jane Eyre, thinks about Mr Rochester locking up his wife in an attic, noting that “she suspected that Mr Rochester’s treatment was broadly in line with Alliance protocol”.

Rose gradually finds she cannot get the voices of famous female writers out of her head. She is drawn towards insurrection and the novel ramps up the tension as a thrilling narrative of revenge and redemption that builds to a dramatic finale.

Widowland is a richly imagined treat, one that should prompt reflections on our low, dishonest times. The craven “faceless MPs” in the novel have plenty of modern counterparts, as do the leaders who have mastered the use of “misdirection” and “distraction” techniques to stop people focusing on “what really matters”. As Rose laments, “people liked the idea of a strong leader – they didn’t much care what that leader stood for”.

‘Widowland’ by CJ Carey is published by Quercus on 10 June, £14.99

Tokyo Redux by David Peace ★★★★☆

David Peace, who moved to Japan in his twenties, spent more than a decade working on Tokyo Redux. He said the various abandoned drafts ran to well over half a million words – and it’s been worth the wait for the third instalment in his magnificent Japan-based trilogy, which started with Tokyo Year Zero (2007) and was followed by Occupied City (2009).

The dead are pervasive in all three books. The opening book, set in 1946, was about the hunt for a serial killer, set amid that city’s post-war rubble. The second, set in 1948, explored the infamous Teigin Bank Case, a robbery that involved the mass poisoning of victims. Tokyo Redux, set in 1949, centres on the mysterious death of Sadanori Shimoyama, president of Japanese National Railways, who goes missing the day after serving notice of 30,000 job losses.

The Japan of this concluding novel is still occupied, and still in disarray, as American detective Harry Sweeney investigates the death of Shimoyama, pieces of whom have been discovered all over the railway tracks of the Jōban Line near Tokyo.

Tokyo Redux is an engrossing novel, but one that has to be read carefully. There are complex timeline switches to 1964, when a former policeman looks back on his actions during the occupation and is forced to reflect on his past crimes, and then to 1988, when Emperor Shōwa is dying and an ageing American translator is given clues that might finally solve the mystery of Shimoyama’s death.

Peace, who was born in Yorkshire in 1967, is one of our most ambitious writers. His Tokyo trilogy is very different from his superb UK-based works such as The Damned United, GB84, or his Red Riding Quartet. It is an intriguing collection, and a shrewd, penetrating depiction of a country with deep, twisted secrets, often hidden by elaborate formalities and ceremonies. Tokyo Redux is a fittingly perplexing and claustrophobic conclusion to a memorable neo-noir trilogy.

‘Tokyo Redux’ by David Peace is published by Faber on 3 June, £16.99

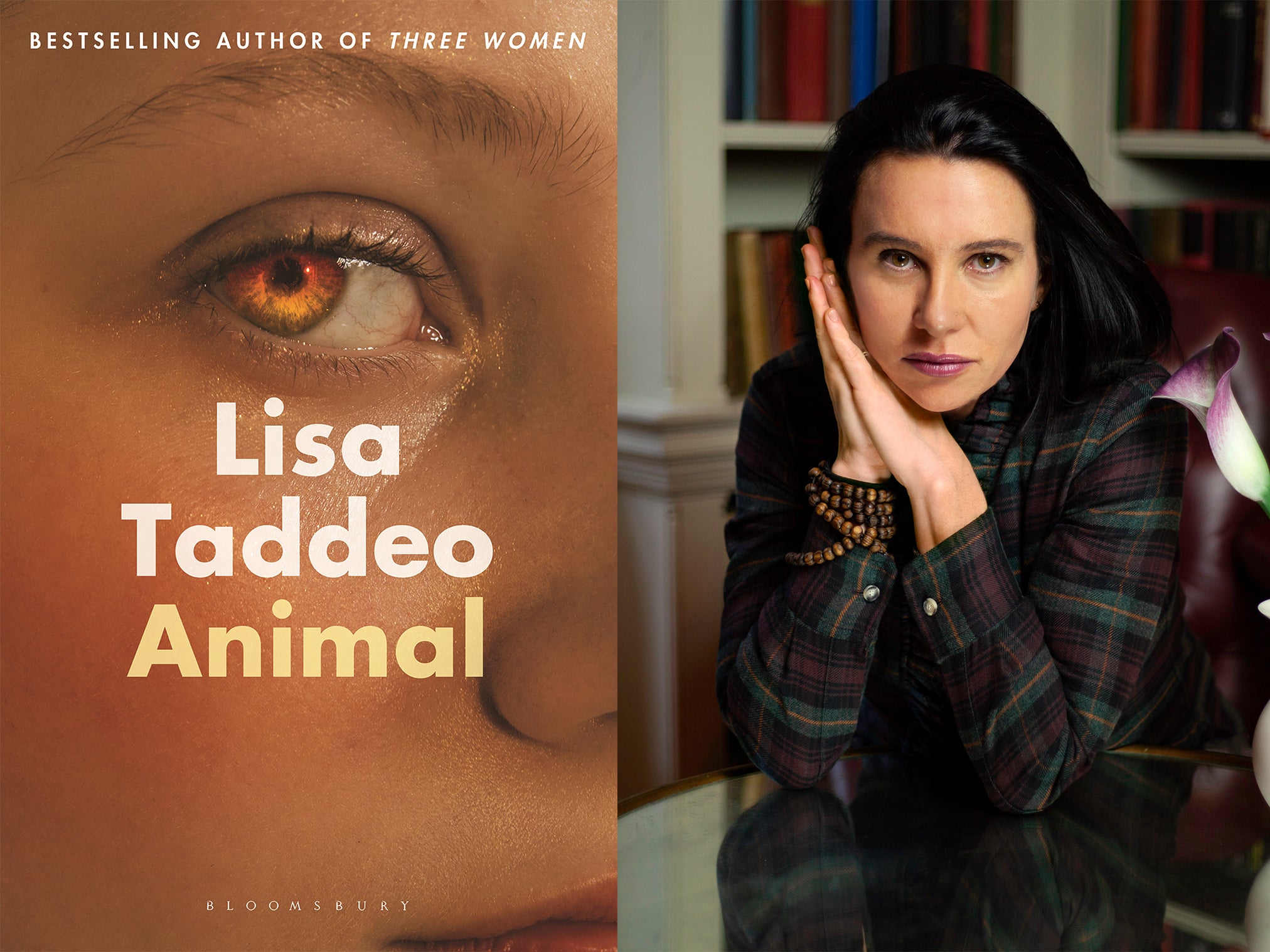

Animal by Lisa Taddeo ★★★★☆

Animal opens with a violent suicide in a New York restaurant, one that prompts the novel’s protagonist, Joan, the former lover of the married man who has killed himself, to flee to California. Post road trip, she reveals the secrets of a dark past that left a “chemical burn in my heart that I cannot cool”. Gradually, in what is part thriller and part confessional memoir, we see what has caused the rage inside her, one that builds to its own deadly conclusion.

Lisa Taddeo has created a memorable character in Joan, a woman who believes herself to be “depraved”. Gradually, as we are shown “a lifetime of suffering”, Taddeo allows us to understand the events, including a horrific sexual assault, that has left Joan so damaged. “The world had set me up to believe that it was women who went mad. It was simply women’s pain that manifested as madness,” Joan admits, in what seems like a key reflection.

Animal is an unsettling book. I wonder about the vicariousness of the misery. I also wonder how many men will read such a challenging novel, however important. Nearly all the males in the novel are as predatory as the coyotes that stalk Joan’s new home in the Santa Monica Mountains. It doesn’t seem to matter whether the ones Joan meets are young or “crushed old men”: they all seem to want to violate her. Joan feels an old man’s eyes “between my thighs like a flare”. A middle-aged guy looks from her eyes to her breasts “so often that I thought he had a tic”, while a youngster at a cash register does not take her eyes off her. “There are a hundred such small rapes a day,” she says.

After Joan hooks up with a bartender in Santa Barbara, she recalls that “we didn’t fuck, I was too afraid he might carry disease. I half-heartedly blew him and let him finish on my chest. I remember the colour was a terrible greenish hue”. There is a bleakly funny account of a fling with an “ugly” man called John Ford – she notes, drolly, that he had never heard of the famous film director who shared his name – in which she recalls, “I felt like a canal that this small balding man was passing through. I’d turned to see his scummy eyes fluttering like a slot machine as he came.” It’s no coincidence that much of the sex in Animal is a joyless, degrading experience. “May you not go around the world looking to fill what you fear you lack with the flesh of another human being, that’s one part of what this story is for,” admits Joan.

The book, written as a clipped first-person narrative, is full of sparkling language. The descriptions of California, under a “despotic” white-hot sun, are particularly vivid. There are also highly disturbing moments, including two accounts of miscarriage.

Joan describes the interior of her brain as “a snake pit”, adding, “I couldn’t survive in there alone”. Some of the most tender scenes are when Joan meets a woman called Alice – a woman she pursues in order to discover some of the truth about her family’s past. Through their interactions we glimpse the empowering solidarity of female friendship and how a friend can rescue you from your own snake pit. Joan’s connection with Alice is one of the few uplifting moments in the story of a woman pushed to the brink.

In Animal, Taddeo tackles distressing subjects – rape, suicide, child sexual assault, murder, miscarriage, dementia, abortion, and adultery – with her own gimlet eye, and the result is haunting. It’s a transfixing read, although how much you actually enjoy the novel may ultimately depend on how much you want to connect with Joan’s story. However, I am sure that there will be scores of readers who will recognise and relate to the dismal truth of Joan’s world, one in which “most men are crabs, crawling around with their pincers out”.

‘Animal’ by Lisa Taddeo is published by Bloomsbury Circus on 24 June, £16.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks