St Thomas Aquinas: Five ways to prove God’s existence

Our series continues with perhaps the major figure in scholastic tradition, Saint Thomas Aquinas

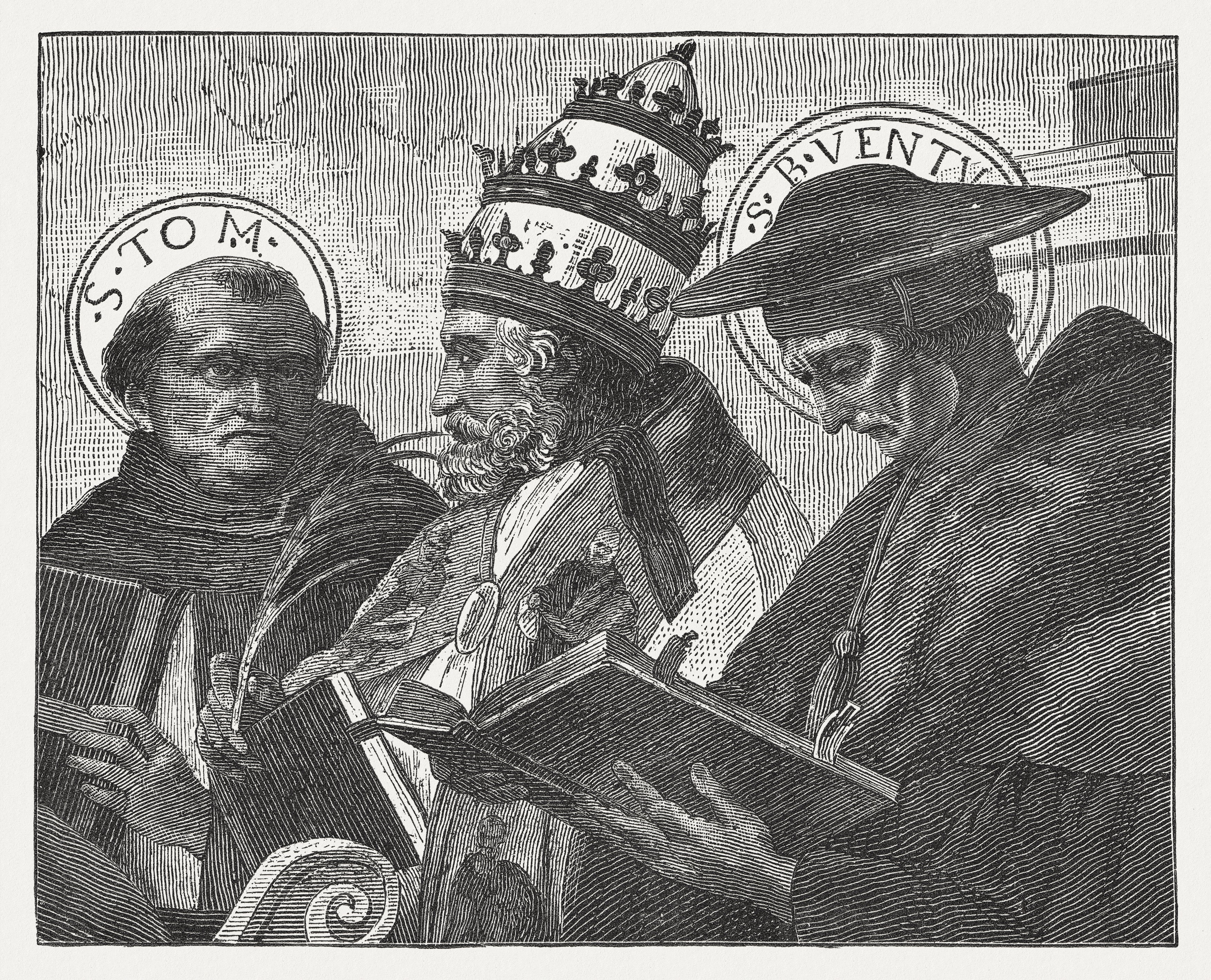

Saint Thomas Aquinas (1225/6–1274) was an Italian Catholic philosopher and a major figure – if not the major figure – in the scholastic tradition. He gave rise to the Thomistic school of philosophy, for a long while the primary philosophical mainstay of the Roman Catholic Church.

The life of Thomas Aquinas ended in a manner not quite befitting a saint and a Dominican friar (the Dominican brotherhood places value on a life of poverty and undertakes the begging of alms). He was born in his family’s castle, the youngest son of Count Landulf of Aquino and Donna Theodora, herself with connections to Norman nobility. His education began at the age of five, when he was sent to the Abbey of Monte Cassino, and continued at what would eventually become the University of Naples.

A devout youth

It was here that the teenage Aquinas came under the influence of the Dominicans, and when his noble family discovered that their son was about to join the brotherhood, his scandalised mother dispatched his older brothers to Naples with orders to abduct him, the aim being to hold him until he saw reason. He was kept a prisoner in the family castle for over a year. On one occasion, his brothers sent a prostitute into his room in a last desperate effort to break his resolve. However, Aquinas chased her out with a burning stick from the fire. His family eventually despaired and relented. Aquinas won his freedom and joined the order.

In 1252 he went to Paris and began to teach. Eventually he took a Chair in the Faculty of Theology of Paris University. He spent the rest of his life moving between learned institutions in Italy and France, throughout it all producing a truly voluminous body of work – millions and millions of words – all the more remarkable given his short life. He had as many as four secretaries taking dictation, largely because of his astonishingly large output, as well as his allegedly appalling handwriting – or perhaps both. The torrent of words stopped abruptly, however, when he had what he took to be a religious experience during mass. “All that I have written seems to me like straw,” he said, “compared to what has now been revealed to me.” A few months later, en route to a church council, he was struck on the head by an overhanging branch. He died shortly thereafter.

Aquinas draws a distinction between conclusions arrived at through reason and the truths of revelation

His enormous output was partly the result of his intellectual power and partly because he lived in remarkably provocative times. The works of Aristotle had recently become available in the West again, sometimes with accompanying heretical but persuasive commentaries composed by non-Christian thinkers of the stature of Averroes. Here were non-believers, reasoning well, who came to conclusions apparently in conflict with Christian teaching. The soul, they argued, is not immortal; the universe was not begun by a single, divine creative act but exists eternally; God knows only himself, not us. While some, at the time, were content to show simply that Aristotle and his commentators must be wrong, Aquinas wrote 12 commentaries on Aristotelian doctrine, arguing that Aristotle was getting at something like the partial truth. It was not just an exercise by him in Christianising Aristotle, but a necessary step to combat heretical thinking.

The influence of Aristotle

It was Aristotle’s methods, as much as his conclusions, which disturbed the scholars of Aquinas’s time. Aristotle claims that one must recognise the difference between what is to be assumed and what is to be proven before thinking can get under way. Knowledge builds on itself, and some disciplines nearer the top of the edifice are dependent on the truths below; they get going with assumptions grounded elsewhere.

Nearer the foundations of the structure are truths every rational person just has to accept if he or she wants to be rational. You cannot play the rationality game and take part in a debate, for example, if you do not accept the Law of the Excluded Middle: there is nothing between the assertion and the denial of a proposition. Only “yes” or “no” count as answers to questions of the form: “Is it true that p?” If you do not accept that minimal requirement on rationality, you are doing something other than arguing; you have removed yourself from the debate. Assenting to some rules is just part of the warp and weft of rationality.

Aquinas draws a distinction between conclusions arrived at through reason and the truths of revelation. Obviously, the latter are authoritative for Aquinas, but (perhaps unusually for his time) he holds that the conclusions of reason in the writings of non-believers, Aristotle in particular, demand serious attention. Most interestingly, he argues that reason itself can arrive at some revelatory truths, and he sometimes adopts Aristotle’s methods in order to do so. Further, his Dominican roots convinced him that one should stand ready to discourse on theology, particularly with those outside the faith. This means that premises must be sought to which even a non-believer would assent.

Perhaps this more than anything else explains the existence and tone of Summa contra Gentiles (On the Truth of the Catholic Faith Against the Unbelievers). Next to his uncompleted masterwork, Summa theologica (Summation of theology), it is the best expression of his unusual attitude towards reason and those outside the faith.

Aquinas’s five ways

An excellent example of Aquinas working with Aristotelian methods is to be found in his famous proofs of God’s existence, the Five Ways or the quinque viae. Though their flavour might be owed to others, Aquinas’s Aristotelian gloss makes his versions of the proofs remarkable. Each begins with empirical truths allegedly accepted by all and proceeds to the conclusion that God exists. We will consider just one, the Second Way.

Things in the world stand in causal relations. To use Aquinas’s example, a stone moves, and this was caused by a stick which pushed it along, and this was caused by a hand, holding on to the stick, which moved it. Nothing, though, is a cause of itself; rather, causes are causes of other things, their distinct effects. An infinite regression of causal sequences is not possible. So there must be a first, uncaused cause, and this, Aquinas argues, everyone calls ‘God’. In other words, one thing starts the whole chain going; one thing which is a cause but is not itself caused by anything else. Similar arguments are run for the existence of a first unmoved mover, a necessity underlying possibility; a perfection underpinning the gradations of the qualities of material things; and an argument for a God to explain the apparent order of the empirical world.

In each case, the argument runs backwards from empirical facts accepted by all – facts of motion, causation, change and qualities – to something responsible for the lot, something rendering intelligible the world around us. The arguments are open to many kinds of objection. One that most exercises philosophers takes issue with the move at the end of each argument, from the existence, say, of an uncaused first cause, to the existence of God: such and such must exist, and this we all call ‘God’.

Why think that the uncaused cause has the many attributes we usually associate with the Christian God? Could there not be many uncaused causes at the back of the chain, rather than one God? Why think that the uncaused cause, if there is just one, is all-knowing, all-powerful and all-good? Maybe it is a rather pedestrian uncaused cause: without much in the way of rationality, only just powerful enough to get things rolling, possibly with malice on its mind. There seems to be something missing, perhaps a premise, between the inference from whatever it is which underwrites the causal sequence to that thing’s being God.

If Aquinas thinks that reason can tell us that God exists, he maintains that it cannot get nearly as far with regard to knowledge of the nature of God. While we are naturally equipped to come to know something of the physical world, our capacity to wonder about the nature of God outstrips our ability to understand. We come by such knowledge as we can get indirectly, by analogy and by negation, and Aquinas maintains that this knowledge is imperfect at best.

What we can know of God

Much of what we can say we know of God’s nature results from negating the properties of material things which we know better. We can say that God is not anywhere, not any time, not changing, not finite, and so on. We can also come to a partial, imperfect understanding of God’s attributes by analogy with our knowledge of some of our properties. God is perfectly good, and we can know something of this by reflecting on what we know of goodness. God wills, and while this is a different thing to human willing, we can have an imperfect grasp of it by analogy to human will.

Still, there are things Aquinas claims can be known about God’s nature, though the story is a complex one. God’s attributes are characterised by Aquinas as consisting in simplicity, actuality, perfection, goodness, infinitude, immutability, unity and immanence. However, our access to this knowledge and the character of the knowledge itself are special. Aquinas argues that knowledge of the divine nature, beyond mere analogy and negation, is possible only in virtue of God’s intervention – grace or the beatific vision. Where reason falters, revelation picks up the slack. We might be able to reason our way to the conclusion that there is a God, but only revelation can tell us, for example, that “God is a Trinity”. Finite beings as we are, though, even grace cannot convey a comprehension of the divine, only an apprehension.

Aquinas’s Influence

It is worth noting that Western philosophy, not just Western theology, owes a debt to Aquinas. It is possible to get the impression that Aquinas’s concerns were just to do with the existence and nature of God, but that would be a mistake. His vast writings include considerations of human nature, government, law, ethics, metaphysics and epistemology, among a great deal else. In all of this, Aquinas’s influence has been large, both inside and outside the church.

Major works

Written between 1261 and 1264, Aquinas’ major work was Summa Contra Gentiles (On the Truth of the Catholic Faith Against the Unbelievers). It contains long treatises on the nature of God, creatures, the end (the purpose, or telos) of creatures, and revelation.

Unfinished at his death, Summa Theologiae (Summation of Theology) is an enormous work, running to 60 volumes. It contains detailed reflection and argumentation which continues to shape religious and philosophical thinking.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments