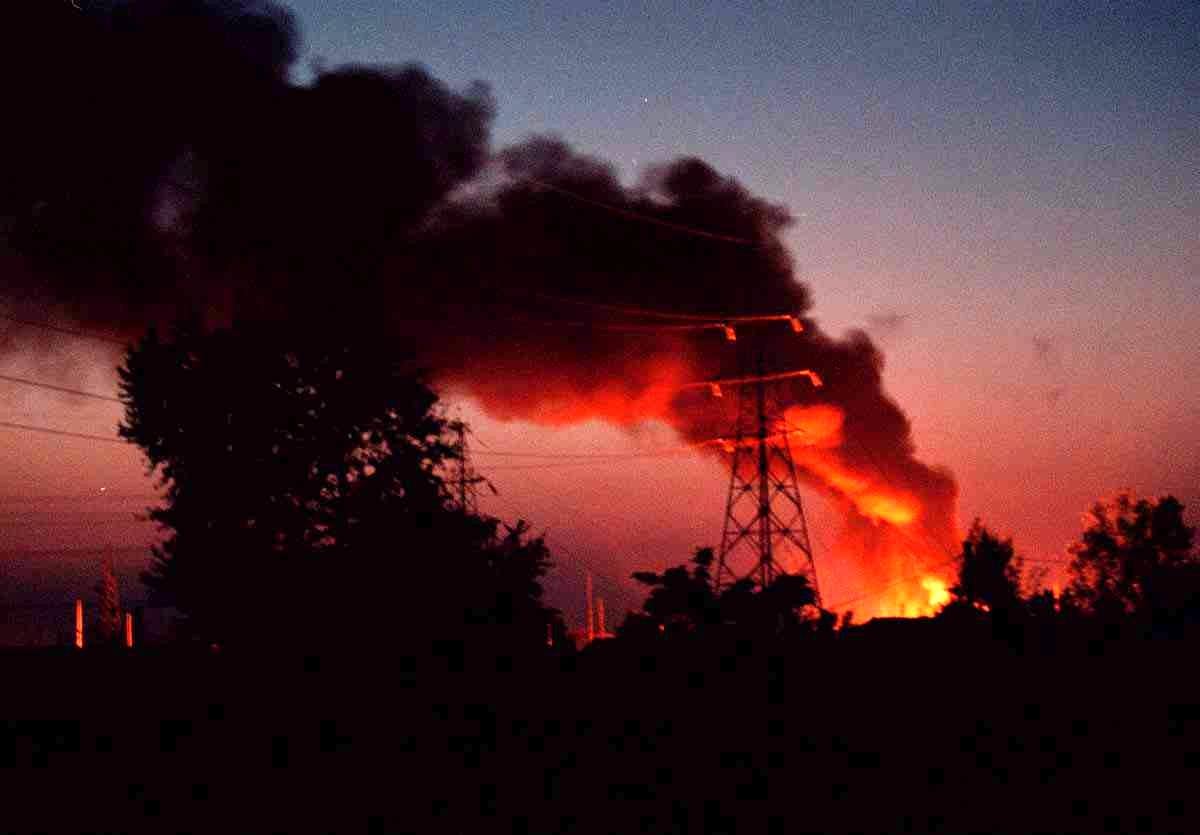

A great orange glow lit the sky: Nato bombs Belgrade

March 1999: From a rooftop, Robert Fisk witnesses the bombing of Belgrade

The explosion was so massive the curtains of our opened window blew in for more than a minute, as if a hurricane had struck the hotel. From the roof late last night, it was all too obvious what had happened.

The noise of jets should have told us. A great orange glow suffused the hilltops beyond Belgrade, flickering and smouldering in the darkness, outlining streets and apartment blocks, even the pale ribbon of the Danube below us. It must have been a munitions dump.

Every few seconds – and we could see this from our vantage point on the roof – there would be another splutter of fire and a track of flame would soar into the sky, a missile presumably set off by the attack. “There are civilians who live around that hill, many of them,” said the restaurant chef, still in his immaculate white jacket, staring towards the hillside with its dark red penumbra.

Who could blame the Serbs for their reaction to this? “I give you bread – you send me missiles,” the waiter had muttered at breakfast, and it was difficult to disagree. The Belgrade bread was fresh and soft, the missiles rather familiar. The Yugoslav air force shot down at least one of them on Thursday night over the Tosca mountain – which accounts for the claims of destroyed aircraft, so swiftly denied by Nato – and several witnesses saw the Yugoslav ground-to-air rocket destroy the American Tomahawk missile in an enormous mid-air explosion. This did nothing to assuage the waiter.

The people of Belgrade had just spent two hours in their basements, street lights switched off and house lights dimmed, after radar showed a large force of B-52s flying towards the capital. The sirens howled over the city but the aircraft never came, just a series of low, distant explosions. And yesterday morning, the streets were almost as deserted as they had been at night, with traffic reduced to a few rattling trams and cigarette vendors the only businessmen.

But no one in this ghost city doubts that the country is at war. Serb television has shown film of Nato bomb damage in the countryside, including a burning aircraft factory at Batunica. I had seen it earlier, blazing away into the night, showers of sparks climbing behind a screen of trees, smoke cowling the fields around it, an old MiG jet still propped pointlessly on a concrete stand beside the front gate. Nor is the Belgrade government making any secret of the targets. State radio has talked of 20 military installations hit in the first 24 hours which – given Nato’s claim of 50 targets in 48 hours – is undoubtedly correct.

But like all wars, this conflict contains its own dark rumours, some true, some plainly false. Studio B Television here talked briefly of heavy casualties among Serb refugees from Krajina when Nato aircraft struck a bomb shelter in which they were said to be hiding in Zarkova. From Kosovo came stories of Albanian “terrorist” atrocities. Claims of village executions in Kosovo by Serb forces are watched on BBC World television, whose broadcasts engender a mixture of astonishment – when, for example, it reported aircraft taking off to bomb Serbia but which never arrived – and hilarity.

George Robertson’s execrable pronunciation of Serb towns produced hoots of derision among diners in my restaurant and I had to leave to survey the city when he announced that the notorious war criminal Arkan had sent his men “touting their wares” – whatever that meant – on the streets of Belgrade. Alas for Mr Robertson’s fantasy, only the cigarette-sellers had wares to tout. Even when the air raid sirens wailed again in the warm afternoon, I could find only a chemist shutting up shop and a father taking his two small sons to a cafe for soft drinks. This is, of course, not a city in which to display a British or American “passport. “Please don’t tell me you reporters in England tell the truth,” a bar owner told me. [...]

“I wish, I really wish the Americans would come here to Belgrade,” my hotel manager, Dragan, announced over coffee. “Then I could go like this.” And he ground his heel into the frayed hotel carpet.

Scarcely an hour later, guests crowded round the BBC to hear a Kosovo Albanian announcing Nato forces might have to enter Kosovo on the ground to save his people. Both Dragan and the Kosovar are going to be disappointed. Nato is not going to risk the bones of a single grenadier in the Balkans, either to fight the Serbs or to save the Kosovars. Which is why, I suppose, Nato has to go on telling us there will be more – and more – air raids.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments