Following the devil’s tracks – revisiting Mostar

Part 1 – June 1994: Robert Fisk returns to the war-torn Bosnian city to see the destruction for himself

You can freeze-frame every moment of the final destruction of the Stari Most bridge. On the videotape timer, the moment is exactly 3.32pm on 9 November 1993. In its last milliseconds of existence, tank shells smash into the west side of the parapet in a cloud of brown dust. Then the entire 16th-century bridge – “a rainbow rising up the Milky Way”, as a traveller to Mostar described it 400 years ago – falls in a slow, lazy way into the waters of the Neretva to be met by a majesty of spray. The tape ends. Press the rewind button and you can rebuild the bridge, the spray falling back into the gorge, the old Turkish stones rising mystically upwards to recompose themselves in their magical span.

That videotape was one of the reasons I had returned to ex-Yugoslavia. I watched it 10, then 20 times, mesmerised by the killing of history, by that sudden act of “cultural cleansing” which erased Mostar’s 500-year chronicle of Muslim life. I had walked across that bridge many times. Over the past two years, flying in from the Middle East, from the centre of the old Ottoman empire, I had reported Sarajevo, visited the Serb concentration camps, interviewed the raped women, despaired of the United Nations. But something about the psychological mechanism of this war always eluded my understanding, a degree of evil that history alone could not account for. Why were the people of Bosnia and Croatia so much more cruel towards each other than the men fighting civil wars in, say, Lebanon or Afghanistan or Yemen? Where did it come from, this desire to kill and rape so coldly, to destroy each other in so brutal a fashion? Was it some quirk of history or upbringing that produced this epic slaughter? And if the 1941-45 civil war between Tito’s Serb-led partisans and Ante Pavelic’s Nazi Croat Ustashe had implanted cancerous cells in the body politic of old Yugoslavia, did no Bosnian Muslim or Croatian or Serb think of the future, rather than the past? And did they not realise that when the United Nations eventually deserts them, when the Europeans finally lose heart, they will still have to live on this land?

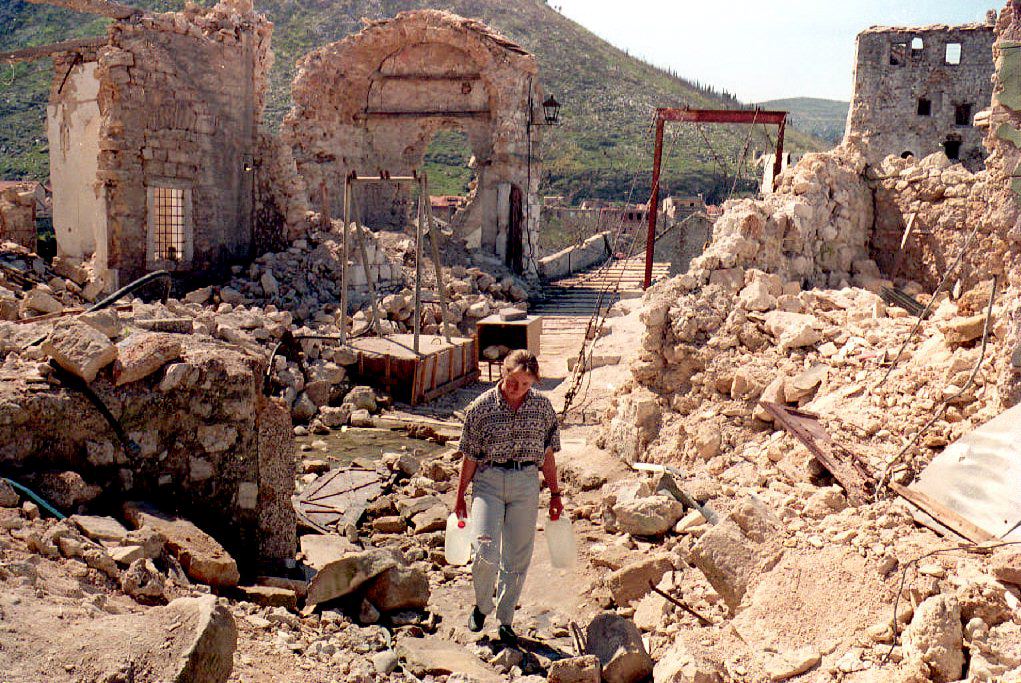

I had watched the destruction of the Stari Most so many times, but once I reached Mostar and stood by the smashed parapet, its absence took my breath away. The old piers of 1566 are now connected by a flimsy rope suspension bridge, a fearful thing whose narrow metal pathway sways from side to side, bouncing and jumping into the air when I staggered across it, as if angrily wishing to revenge itself upon human folly by hurling me into the frothing waters below.

On the eastern side, there still survives four square feet of knuckled stone, the polished, worn ridges which the Turks originally inserted into the kapia to prevent travellers from slipping. Ten months before its destruction, I had walked over them, my shoe leather sliding on these knuckles, confident that the tyres slung over the parapet and the faith of Mostar’s people would preserve a bridge which was glued together with eggshells and dung. Now, on the eastern edge of the drop, I found an old man, coughing in the dusty air, transfixed by the spirit of the bridge that was no longer there. “We are like stray dogs now,” he muttered. “Our people have lost their direction.”

I had a brother killed also and my mother died of a heart attack five days later. But now I want to know something: for whose sake did all these young men lose their lives?

A girl called Melissa asked me to telephone a Muslim family in Serb-held Bosnia. “Just say hello to them from families in Mostar,” she had written next to the telephone number. “Tell them we are alive.” She pointed at the river. “You cannot imagine what we felt like when the bridge was destroyed. We felt as if part of our soul had been destroyed. The Croats have a culture, a civilisation. How could they do this? This is also their culture...

“But there’s something very strange. When we heard the bridge was gone, first we felt our soul had gone too, then we also felt much stronger.”

Melissa was out there on the edge of psychoanalysis, exploring the same questions I was trying to answer. How could they destroy a thing of beauty like the Stari Most or the 16 mosques of Banja Luka – or, for that matter, the Serbian Orthodox church here in the Muslim sector of Mostar? “The Serbs were shelling us,” a Bosnian government official explained later. “Our fighters were very angry.”

In the centre of Mostar, the public park is now a crowded Muslim military cemetery. And it was here that we found Amra Listo sitting by her husband’s grave. “Semir Listo,” it said. “1951-1993.” She was well dressed with smartly cut short hair. She had put on jewellery to visit her dead husband and she talked to us without a hint of emotion. “We had been married for 21 years and have three children. He was on guard duty in Sanski Street. Our house is on the front line in the Cernica district and the Croats tried to break through many times. We have soldiers billeted in our house. Semir and I knew the risks.

“It was 24 October, at night. I was at work in the public kitchen because we were besieged by the Croats then. A few of his fellow soldiers came to see me and tell me what happened. He was shot in the head by a Croat sniper.”

Amra had brought fresh water for the jars of flowers on Semir’s grave. “He always said his only aim as a soldier was to have a free town in which his family could live,” she said. “He loved Mostar. He was in the local football team. I had a brother killed also and my mother died of a heart attack five days later. But now I want to know something: for whose sake did all these young men lose their lives? I want peace so badly now. But could I live with Croats again, after the horrible things they have done? You know, I tell my younger son that the Ustashe killed his father and that he must remember that. It will not be easy to forget all of this. The only thing my children have left from their father is a rifle... they have this wooden grave marker and his rifle.”

In fact, the children have a picture of their father, a passport-size snapshot of a dark-haired man with a moustache, fixed behind a glass frame above Semir’s grave. Beside it, typed neatly on a single sheet of paper, was what must be one of the most moving laments of the Balkan war, a poem written by Semir’s 21-year-old daughter Lara:

But all disappeared in the autumn night and became strange forever.

That was when sorrow moved in my soul and became its eternal inhabitant.

My dear father, only in dreams I am happy now because you are in those dreams.

Yet it’s all so short because when I wake up, the only thing that’s left is the mark of the tears and the painful truth that you no longer exist.

I’ll keep your dear image forever in my soul, although tears are slowly suffocating me as I’m writing you these lines.

My Mostar fleur-de-lys, I, your daughter Lara, will always love you.

Sleep peacefully, soldier of Cernica.

In your interrupted dreams, they killed you.

Keep dreaming your interrupted dreams.

Amra leant forward and kissed her husband’s tiny portrait, leaving lipstick on the glass. “You will excuse me,” she said. “I have other graves to tend now.”

In Ivo Andric’s novel, The Bridge over the Drina, a 19th-century Muslim shopkeeper tries to explain God’s creation of Bosnia. “When Allah the Merciful and Compassionate first created this world,” he says, “the earth was smooth and even as a finely engraved plate. That displeased the devil who envied man this gift of God. And while the earth was still just as it had come from God’s hands, damp and soft as unbaked clay, he stole up and scratched the face of God’s earth with his nails as much and as deeply as he could. Therefore ... deep rivers and ravines were formed which divided one district from another and kept men apart ... And Allah felt pity when he saw what the Accursed One had done ... so he sent his angels to ... spread their wings above those places and ... men learnt from the angels of God how to build bridges, and therefore, after fountains, the greatest blessing is to build a bridge and the greatest sin to interfere with it...”

The sin was committed in Mostar last year, as it was in Dubrovnik the year before, as it is still being committed against the last mosques in Serbian Bosnia today.

IT WAS impossible to be in Mostar again without trying to find out what had happened to the Muslim women I met just over a year ago, victims of the rape camps set up in 1992 when the Serbs “ethnically cleansed” their way down the valley of the Drina. I tramped through the rubble to the old Austro-Hungarian apartment block where I’d met Ziba and her friends last year. It was a burnt ruin, her refugee home turned to ash after this year’s Muslim-Croat fighting.

As I crossed the road to the wreckage of Mostar’s railway station I found three men in old blue uniforms sitting on an embankment. “The railway is cut off by the Croats,” one of them said. When did the last train leave? “Eighth of April 1992,” the man said immediately. “The war had started. It was a train to Zagreb. I don’t know if it ever got there.”

We walked through the departure hall where black stains and torn clothing lay near the Sarajevo platform. “Fifty-two people were killed here by a single Serb shell,” the man said. Grass was growing over the tracks; three marooned railway wagons stood in a siding.

I approached another group of men sitting on the other side of the station and produced a copy of last year’s Independent with a photograph of one of the raped women. She used to live near the station, I told them. Did they know her? Had she survived?

The men looked closely. And one of them shouted: “That’s my sister-in-law!” Which is how we found Ziba, thin, chain-smoking, living now in an old Serb house above the railway tracks.

“Croats came and tried to take the building you met me in,” she explained. “My husband was wounded by a sniper and I was hurt by a Croat shell.” She carefully pulled off her right shoe to show a deeply scarred wound on her ankle. “For two months, we lived in the basement of a burnt-out department store to avoid the shells. Then, later, we tried to found a group among all the women who were raped by the Serbs and who were now refugees trapped in Mostar. We called it ‘Mariam’ and we meet once a week in each of our homes.”

The name seems carefully chosen to purify Ziba and her friends. Mariam is the Islamic name for the Virgin Mary. In a tiny room filled with the dark-blue fumes of home-made cigarettes the women talked again of their weeks of gang-rape at the Kalinovik camp, of the Serbs’ intention to make them all pregnant. Last year, Ziba had told me how a Serb called Pero Elez and his friends had kidnapped the 10 most beautiful girls from the camp. They had disappeared. Now Ziba had news of them. Nine had been freed after being raped. The tenth, a 17-year-old called Emelja, had become pregnant and was so shamed by this that she had elected to stay behind, alone, in the town of Foca, among the Serbs who raped her.

I met other women, one of them raped by Croats outside Capljina last year, betrayed, she said, by a Serb woman called Branka Zalankovic to whom she had given shelter from the Croats. “Because I was a Muslim, I thought protecting her was the right thing to do, according to the Holy Koran...” A woman called Samija was freed by Serbs at the Kalinovik camp after she had agreed to collect the bodies of Serb soldiers who had died in a minefield. She was just 21: “It was at night and the mines were everywhere. I went with three other women. I don’t know how I did it. The bodies were in parts – arms, legs, heads. We collected all these pieces of flesh and put them in plastic bags. We will have nightmares about this for the rest of our lives.”

Ziba couldn’t understand why nobody cared. None of the 185 women who were in Kalinovik has been able to leave Bosnia since their ordeal. “We are angry that nobody came to help us,” she said. “The rest of the world says it is interested in helping us but that’s just talk. I only want to go back to Gacko and start a new life. But I can’t see any end in sight. We can never live with Serbs or Croats again after what they’ve done to us. We thought they were our brothers, but now we know who they are.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments