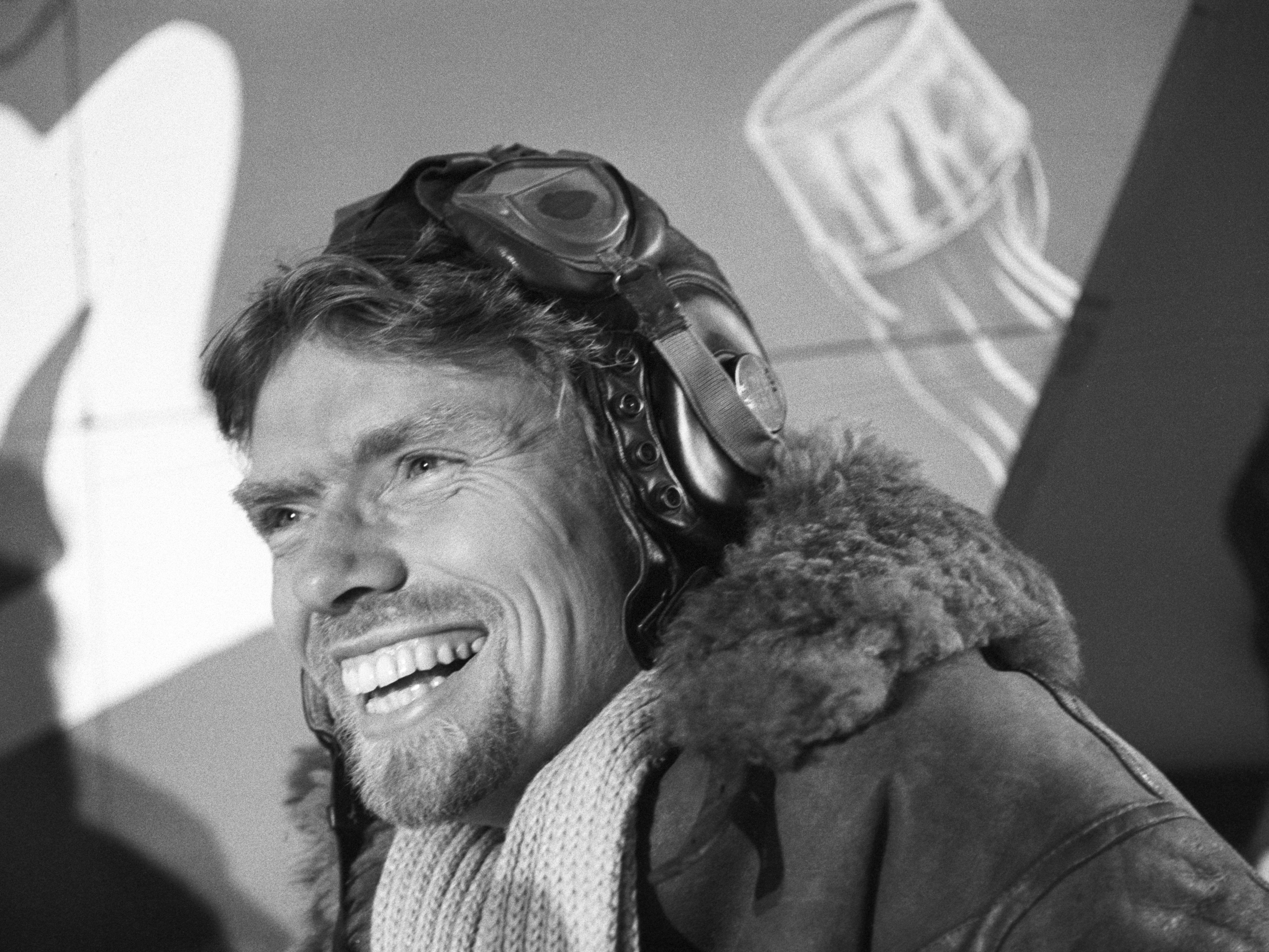

Will winning the billionaire space race be Richard Branson’s greatest achievement?

He’s a man who cannot turn down a challenge and, for the most part, he can find a way to success in whatever venture he turns to. As he prepares to pip Amazon’s Jess Bezos to become the first billionaire in space, Sean O’Grady takes a look back at his extraordinary life

Say what you will about Sir Richard Charles Nicholas Branson, or “Beardie” to his detractors, but he’s not afraid of a challenge. Soon, with luck, he will be the first billionaire in space, which is more meaningful than it sounds, given the competition. If it all goes to plan, Branson will be on board the next test flight his Virgin Galactic winged rocket ship (a cross between a plane and a missile) departing Earth (New Mexico) on 11 July. In doing so, Branson will beat Jeff Bezos, of Amazon fame and fortune, into space by nine days and, almost as important, overshadow Bezos’s remarkable PR coupe of last week when he arranged for the 82-year-old Wally Funk to be the first passenger in space. She trained as an astronaut in the 1960s, but, for reasons that are unforgettable, the time was not right for a female to take that giant leap. According to the corporate hype, Branson is “Astronaut 001”, and his role is: “Evaluating customer space flight experience” (though all passengers will be Virgin staff).

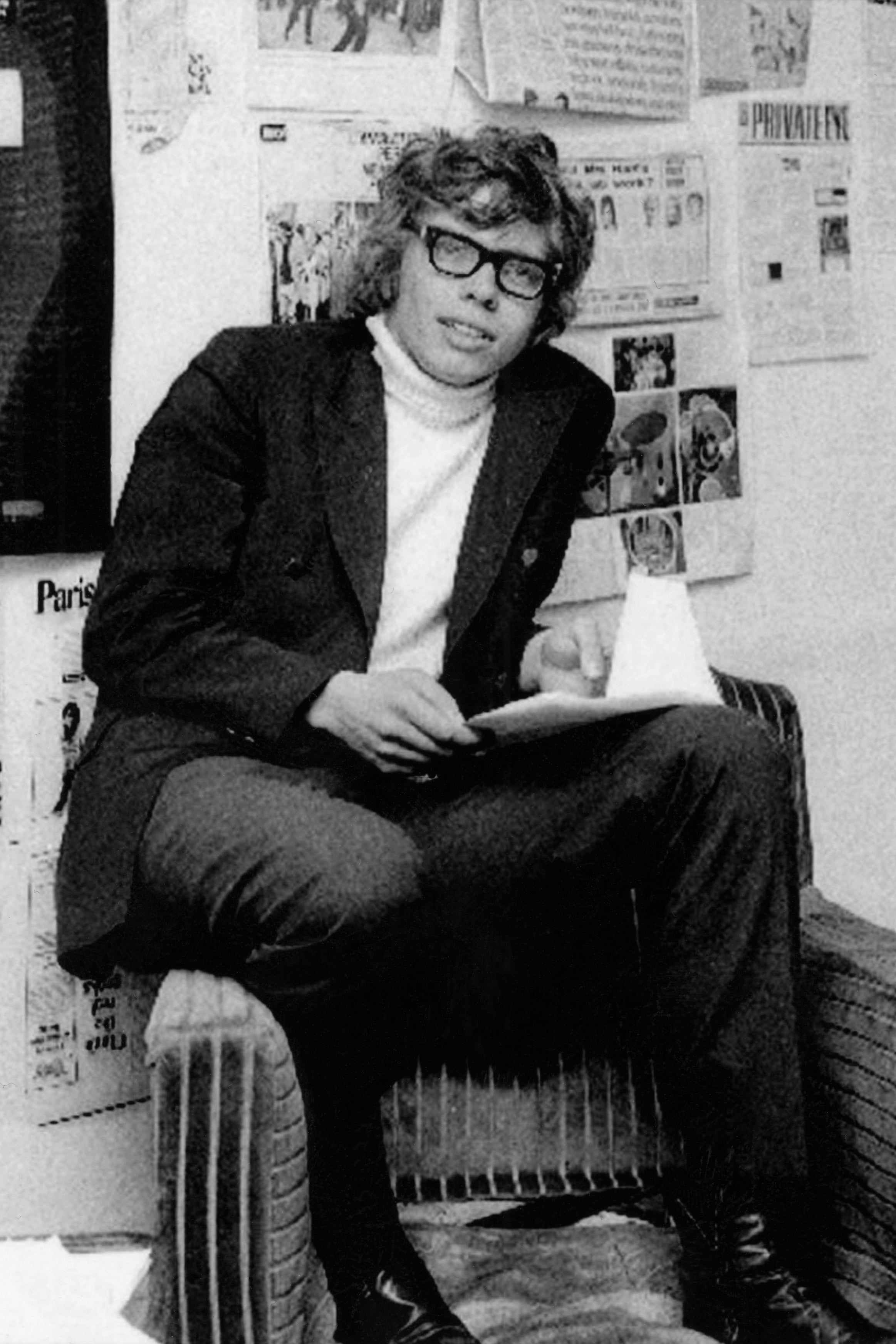

It is a typical Branson move. It is cheeky, indeed audacious, of course, and demonstrates his alertness. A half-century ago now he founded his business empire when he observed that you could undercut the regular high street record stores (we’re talking golden era of vinyl here) by acquiring discs that were certified as destined for export and thus exempt at wholesale prices from purchase tax (the forerunner of VAT), which was levied at 33 per cent. That translated into a big saving for the record buyer, a big profit for Virgin Records, but a big legal problem and expensive settlement when the tax authorities caught up with him. The bill was so large his parents had to mortgage their home to pay it off for him.

The charge of tax evasion has haunted him ever since. Decades later, during the financial crisis of 2007, Branson spotted another opportunity and tried to buy the failing Northern Rock bank, Vince Cable got up in the House of Commons and asked whether such a person would be fit and proper to own a financial institution. It was a fair question, and Branson’s deal collapsed. Still, Virgin Money went on to buy the bank in 2011.

Such is the pattern of Bransonism. Identify a gap, then go for it, almost without due diligence or anything boring like that – summed up in the title of one of his many books (managed by his own Virgin branded publishing house, naturally), Screw it, Let’s Do It: Lessons in Life. It suited his career very well, and his Virgin Record label (founded in 1972) signed all kinds of then-unknown talent, from Mike Oldfield (Tubular Bells was a hugely lucrative album) to the Sex Pistols to Peter Gabriel and Boy George.

When the American and British governments gingerly started to liberalise the major air routes in the 1980s, Branson wasn’t the first to take a risk and start a service (that was Freddie Laker), but from 1984 until the Covid pandemic, Virgin Atlantic was to be the most successful of the entrants (it is co-owned by the now unfortunately named Delta).

This fascination with mass transportation manifested again in the 1990s. When the Major government decided to sell off British Rail it was entirely predictable that Branson would be after a franchise or two, and, with some controversy, Virgin Rail snapped up the West Coast mainline and Cross Country franchises. Now, in a more fanciful way, and following fellow billionaire, space and transport enthusiast Elon Musk, Branson has invested in Hyperloop, a company that aims to power rail services through a series of tubes and vacuums that Musk started backing in 2014. Branson, like Musk and Bezos, is also a great fan of science fiction, though Branson’s resources don’t stretch, as Musk’s do, to establishing a human colony on Mars.

It is almost impossible to comprehend the variety of ventures that have had the Virgin label slapped on them. Some have been phenomenally successful – mainly the airline with its famous red livery, photoshoots with Branson and the glam air hostesses (it was launched in a less politically correct era) and opulent upper class compartments. Others have been, frankly, flops, as if conceived as almost academic exercises in seeing how far the Virgin brand could be stretched – Virgin Cola, Virgin Vodka, and incursions into fashion, cosmetics and Formula One pushed the limits of the brand too far. Yet Virgin Broadband, Virgin Holidays and Virgin Media have worked much better.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Branson’s empire was often held up as an exemplar of “brand value”. There was a certain cult of brand, and Branson was a principal and high profile beneficiary. In his case, brand was sometimes all there was to his businesses, and he was an early, pre-dot.com bubble, pre-internet pioneer of building up businesses that commanded huge stock market or private valuations but which made little money or operated at substantial losses (like, say, Uber or Tesla today).

Today the principal arms of the Virgin empire are typcially joint ventures with larger or more experienced players, plus a very large licensing income from companies that use the Virgin brand (whether Virgin now owns them, part-owns them or has no equity stake at all). The mature Virgin empire, as it reaches its half-century, is beginning to resemble a comfortable annuity, offering a reliable income to Branson and his family.

Not as comfortable, though, are many of Branson’s businesses – travel, airlines, hotels, top-end holidays, gyms and even a cruise line – which were in the sadly perfect position to be hit hardest by Covid. Branson even asked for state aid to prop up his airline. His political contacts seem to have peaked in the time of Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair, both big fans of this emblem of British entrepreneurship. Branson was a big Remainer, which can’t be helpful these days.

$5.6 billion

Branson’s estimated net worth

His, though, is far from a rags to riches story, like that other poster boy, Lord Sugar. His paternal grandfather was a high court judge and knight of the realm, his father a cavalryman, and his mother something of an entrepreneur herself. Branson attributes much of his success to his mother’s enthusiasm and support, though it sometimes comes across a bit cheesy – “my mother taught me never to give up and to reach for the stars”. Her example was a fine one of striking out and trying new things – she’d been a Wren during the Second World War. Afterwards, she was an air hostess, ran a property business, was a military police officer, a probation officer, and made more money from selling wooden decorative boxes to put paper tissues into.

Branson also owes something to his parents for paying for his education at Stowe School, and to mum for funding his earliest business adventures. The legend goes that she found some jewellery in the street and, the police being unable to find the owner, she then sold the gear for £100 and gave it to her boy (worth about £2,000 in today’s money). With that, Branson was briefly a dealer in Christmas trees and budgerigars. (Presumably he bought those “cheep”). A closer parallel than the likes of Sugar would be the young Michael Heseltine. Like Hezza, Branson is a dyslexic, started his businesses with a modest sum from his family and took advantage of the boom in university expansion and student numbers in the late 1960s. Heseltine launched a graduate jobs guide, the beginnings of his Haymarket empire, while Branson started a magazine, Student. Politics though, as a career, hasn’t attracted Branson. Thatcher appointed him briefly as her “litter tsar”, while Blair thought he might make a good Mayor of London. His views on drugs (pro-decriminalisation) were ahead of their time.

The risk-taking extends to Branson’s personal safety, and his physical recklessness cannot be staged just for publicity purposes (though it has certainly generated plenty). Space is not the first frontier he has crossed. He had to be rescued by an RAF helicopter after one of his attempts on the transatlantic speedboat record ended in the vessel capsizing. Another pointless record attempt was successful –the first crossing of the Atlantic Ocean by hot air balloon, but it ended, after 3,000 relatively uneventful miles with the dirigible almost exploding and plummeting to earth in a field in Northern Ireland. It is no joke to speculate that old Beardie might not return to us. At a mere 70 years of age (he’ll turn 71 on July 18, hopefully on terra firma), it would be even more of a shame, seeing he has almost House of Windsor longevity – dad Ted died at 93 years old 10 years ago, and mum Eve passed away earlier this year from Covid complications, aged 96.

You cannot live a life as (literally) racey, high profile and eventful as Branson’s and not attract some bad publicity along the way, to put it mildly. The most serious accusations against Branson emerged a few years ago during the #MeToo movements revelations, when he was accused of ‘motorboating’ Joss Stone’s backing singer, Antonia Jenae. The incident is said to have occurred on Necker Island in the Caribbean, just one of Branson’s many sumptuous homes around the world, the most breathtaking of which is probably the large slice of South Africa next to the Kruger National Park, complete with a tabletop mansion to admire the views and the wildlife.

In a statement on the incident, Branson’s representatives said: “Richard has no recollection of this matter. Neither do his family and friends who were with him at the time. There would never be any intention to offend or make anyone feel uncomfortable. Richard apologised if anyone felt that way.”

He is certainly an emotional soul, if the reports are anything to go by, when it comes to money and the businesses he has created. He was said to have wept when he sold his record label to EMI in 1992, for $1 billion, which must have been some consolation; and again more recently when he was pushed into divesting a share in his airline. His private life, however, is kept fairly, well, private. His first marriage was to Kristen Tomassi, and lasted from 1972 to 1979. They had a daughter, Clare Sarah, who died at four days old. He has a daughter, Holly, and son, Sam, with this second wife, Joan Templeman.

Branson’s business interests are famously complex and opaque, with some domiciled in the British Virgin Islands (for personal rather than tax reasons, Branson insists). Although often mentioned in the same breath as his fellow space-mad, sci-fi crazy billionaires, Bezos and Musk, Branson is a pauper by comparison, worth, as far as can be seen, about £3.6 to £4.3 billion, against about £144.6 billion and £123 billion for the Amazon and Tesla founders respectively.

It is another small triumph of PR that Branson is featured on a recurring Spitting Image sketch lounging around on Mars with Jeff and Elon, shooting the breeze and getting high. He’s obviously still one of the richest humans on this planet, and he is globally famous. You can almost forgive the kind of cringe-inducing bombast that adorns his Twitter profile: “Tie loathing adventurer, philanthropist & troublemaker, who believes in turning ideas into reality. Otherwise known as Dr Yes at @virgin”. Yet he is flawed and has had his share of failures. His genius is that they are hardly remembered, while the triumphs - epic enough, too - continue to dazzle us. Oddly, the Virgin brand he created has sprinkled a little stardust over him, now, with the Virgin Galactic journey. Some have said in the past that Branson’s toothy grin was so bright, and his ego so large that they could be seen from space. Soon we will find out if they can be seen from earth, too.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments