Tarantino, Bruce Lee and China’s spat with Hollywood

The fallout between the ‘Once Upon a Time in Hollywood’ director and Bruce Lee’s daughter has added significance given the ongoing trade war between their two countries, writes Geoffrey Macnab

Imagine the scene. An all-American movie star such as Clint Eastwood, Gary Cooper or John Wayne is relaxing between takes on a movie set, hanging out with the extras. The star challenges a diminutive Asian-American stunt man to a fight and is promptly beaten up. His lumbering cowboy moves are no match for the southern fists and northern kicks action of his kung-fu expert rival. The Asian martial artist humiliates the Hollywood legend.

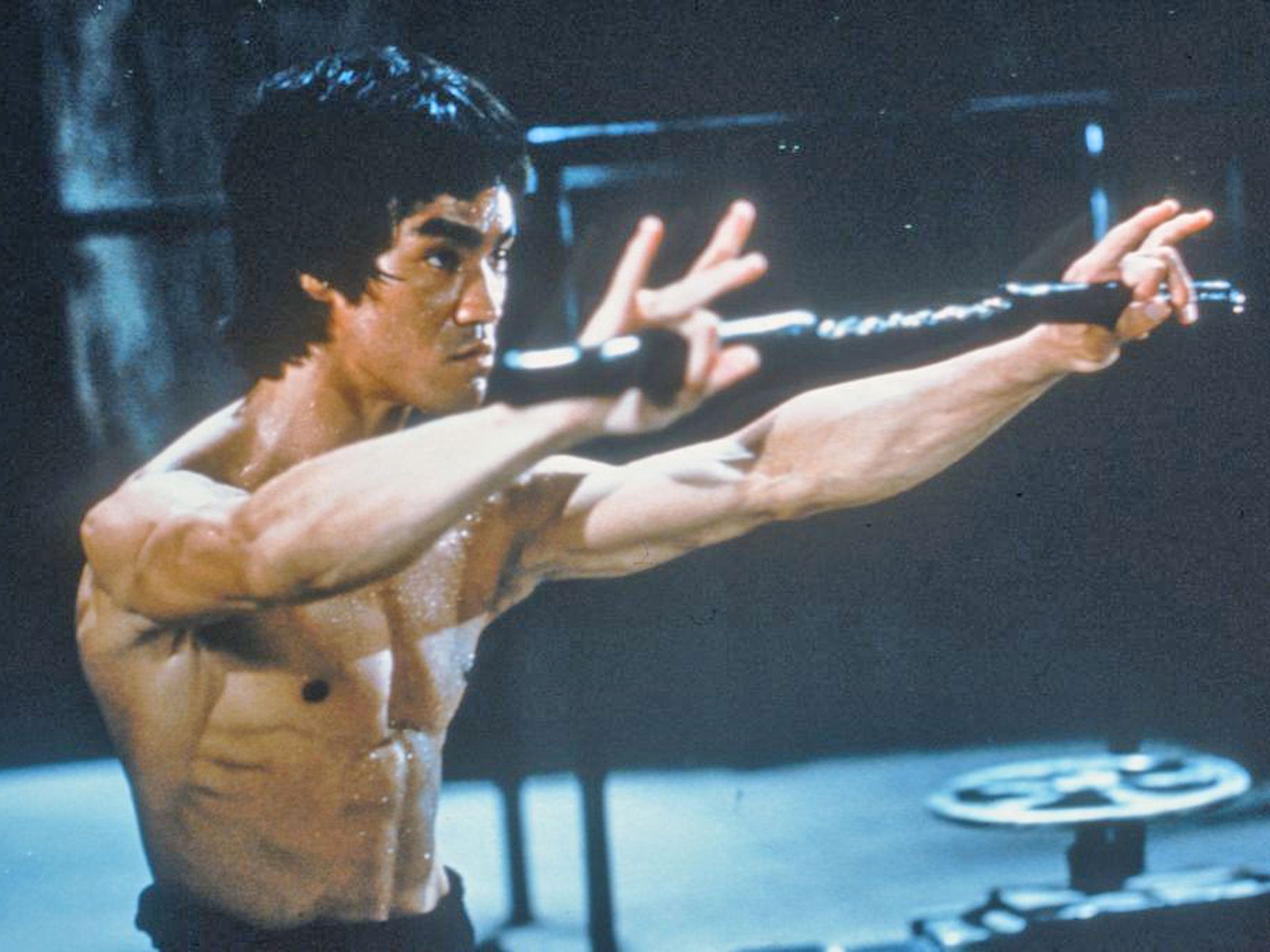

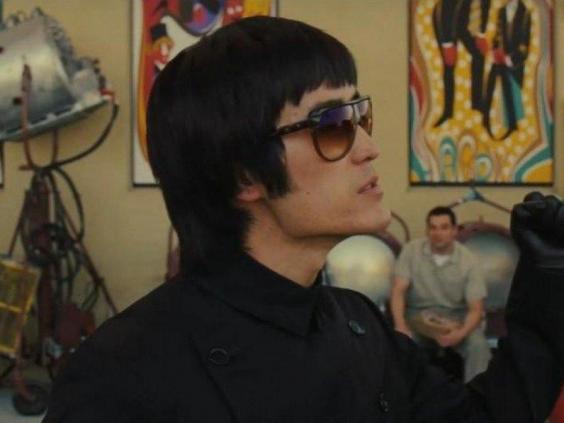

This is the reverse of what happens in Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. Tarantino shows Hong Kong-American star Bruce Lee coming off very much second best in a tussle behind the scenes on Lee’s TV series Green Hornet with Cliff Booth, a rugged stuntman played by Brad Pitt. Martial arts icon Lee is shown as a preening and conceited figure, boasting that his fists are lethal weapons and that he could take down Muhammad Ali, before he suffers his comeuppance.

At the time of the film’s US release in August, Lee’s daughter Shannon Lee expressed her outrage at what she claimed was a skewed portrayal of her father, based on second-hand sources, by a director who had never met him. Her complaints reached China’s National Film Administration, which last week cancelled the release plans for Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, originally scheduled for 25 October, after Tarantino refused to re-edit the film. Although no official explanation was given for the film being pulled so close to its opening, the violence and the demeaning characterisation of Bruce Lee are understood to be behind the decision.

The spat between Tarantino and Shannon Lee can’t help but assume an added significance during the ongoing trade war between the US and China. Pitt’s stuntman beating up Bruce Lee didn’t just offend Chinese sensibilities – it risked exacerbating tensions between the world’s two biggest film industries. As the Hollywood Reporter noted, the Chinese release of Tarantino’s ninth feature was forecast to push the film’s global box office over the $400m (£300m) mark. Instead, if the film isn’t seen in China at all, Tarantino’s backers Sony Pictures will lose a small fortune.

China is driving growth in the global film business is expected soon to outstrip the US as the most lucrative film market. Tens of thousands of new cinemas have opened in the country over recent years. The Chinese are also investing heavily in foreign film companies. The giant, Beijing-based Dalian Wanda Group bought leading US exhibitor AMC in 2012. Dalian Wanda has since sold on some of its stake in AMC as it looks to reduce its overseas debt but still partly owns what has is now the biggest cinema chain in the world (and whose holdings include the UK’s Odeon Cinemas) Wanda also owns Legendary Entertainment, the company behind Godzilla and Jurassic World. Fellow Chinese company Alibaba has a stake in Steven Spielberg’s Amblin Partners and has invested in such recent Hollywood blockbusters as Mission Impossible – Fallout and the ill-fated Gemini Man. Tencent Pictures is one of the backers of Oscar contender, A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood.

Not that Hollywood studios, or western filmmakers in general, have had much success in cracking the Chinese market or that Chinese investments in Hollywood have opened up western markets for Chinese filmmakers.

Censorship and human rights issues, offended sensibilities and cultural confusion continue to dog the fortunes of western films in China. Tarantino’s problems with his portrayal of Bruce Lee follow on from similar difficulties other filmmakers have also faced in getting their films played in China. On the other side of the coin, Chinese actors and filmmakers have struggled for recognition and respect in the west. It is telling that Zhang Yimou’s wildly flamboyant martial arts movie, Shadow (2018), wasn’t even given a cinema release in the UK but limped straight on to DVD.

The UK is one of many countries that, in recent years, rushed with an indecent haste to sign film co-production treaties with China, but there is little evidence of any meaningful collaboration between the two countries since the treaty was signed in 2014. Meanwhile, British distribution companies who used to release Hong Kong and Chinese films by the dozen 25 years ago (when filmmakers like John Woo, Ringo Lam and Wong Kar-wai were in their prime) rarely go near Chinese cinema today.

Under the current arrangements between Hollywood and China, 34 foreign “quota” films are allowed into Chinese theatres each year on a revenue-sharing basis, while other titles can be shown in cinemas by local distributors, who license them from foreign partners for a fee but don’t share the profits. Co-productions such as period epic/monster movie The Great Wall, made in China but starring Hollywood’s Matt Damon, can get around the restrictions. However, such films have rarely turned out well.

One of the more bizarre instances of a western movie hitting a great wall in China involved Disney’s Christopher Robin, a live-action, family-friendly drama starring Ewan McGregor that got middling reviews and whose biggest drawback at the time of its UK release last year seemed to be its extreme blandness. It was kept out of Chinese cinemas on the grounds that Winnie the Pooh looked like Chinese leader, Xi Jinping. In his journey east, AA Milne’s cuddly teddy bear from the Hundred Acre Wood had somehow metamorphosed into a subversive symbol of political resistance in China, a bit like Paddington turning into a member of the Baader-Meinhof gang. You can understand why the Chinese authorities were so upset about the wildly irreverent and abrasive animated TV series South Park, which recently devoted an entire episode to debunking censorship in China, but Pooh Bear is surely a different kind of agitator altogether.

The authorities are even more draconian with their own actors and filmmakers than they are with foreigners. When Chinese mega-star Fan Bingbing, who had appeared in an X-Men movie in Hollywood, as well as in a string of film and TV hits in China, was caught in a tax evasion scandal, she suddenly vanished from public view for several months, apparently because she was under house arrest. When she resurfaced, she was in disgrace. Her case highlighted the contradictions in a country with a communist government trying to deal with a money and glamour driven business like the film industry.

With such huge numbers to motivate them, filmmakers are prepared to accept whatever Faustian bargains they’re offered to get their movies released

While Tarantino is refusing to re-edit Once Upon a Time in Hollywood for Chinese audiences, the team behind Bohemian Rhapsody had no compunctions about cutting three minutes out of their film including key references to Freddie Mercury’s homosexuality. Released as an arthouse film, Bohemian Rhapsody grossed just over $11m in China – a strong result albeit one only achieved after the producers capitulated to the Chinese censors.

Often, filmmakers are ostracised on grounds that have nothing whatsoever to do with their own work. Swedish director Ruben Ostlund’s The Square, the arthouse film that won the Palme D’Or in Cannes in 2017, was released all around the world to huge acclaim, but wasn’t shown in China, reportedly because the authorities there were still angry about one of the recipients of the Nobel Prize. South Korean director Bong Joon-Ho’s film Parasite won the Palme D’Or in Cannes this year but hasn’t reached China, either. A planned screening at a Chinese festival this summer was cancelled at the last minute, ostensibly for “technical” reasons, but the film appears to have been caught up in China’s ongoing blockade of Korean film and TV, prompted by Chinese disapproval of South Korea’s adoption of an American-backed missile defence system.

By the same token, when China is making friendly trade or diplomatic overtures to a country, films from that country will suddenly turn up in Chinese cinemas.

For foreign filmmakers, China can still seem like a promised land. Everyone knows the problems: the censorship and logistical hurdles they face in getting their films into the country and the equally daunting challenges in getting any profits out of it. (Under the revenue sharing terms on bigger movies, western partners only see a small part of the returns. Veteran film trade journalist Mike Fleming recently wrote that, even if Tarantino’s movie was shown uncut, “the 25 cents on the dollar that China kicks back to US studios on its movies can’t be worth the indignity for an auteur like Tarantino to have to compromise his vision”).

However, China was worth over $600m in box-office revenue to Avengers: Endgame, an enormous figure no matter how much of the loot stayed in China. This is also a country where an arthouse title like Lebanese director Nadine Labaki’s Capernaum can gross $50m and a small Japanese film like Hirokazu Kore-eda’s Shoplifters can earn over $14m in cinemas. With such huge numbers to motivate them, filmmakers are prepared to accept whatever Faustian bargains they’re offered to get their movies released.

Sometimes, little European films spurned in their own backyards have turned into runaway hits with Chinese audiences. This was the case recently with Prey (2016), a low-budget Dutch horror film about a bloodthirsty lion that escapes the local zoo and goes on a killing spree in downtown Amsterdam. It grossed $231,000 when it was released in the Netherlands three years ago and looked to have sunk without trace. However, a Chinese distributor bought it, retitled it as Violent Fierce Lion and marketed it as if it was Jaws done on land. It was released earlier this year in China on 4,000 screens and made over $5m during the opening weekend. That would have been very good news for the producers if it hadn’t been for the fact the film had been sold to China for a flat fee. None of the profits filtered back to the Netherlands.

In Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, Tarantino caricatures Bruce Lee as an arrogant motormouth. The portrayal is disrespectful – but it also provides one of the funniest scenes in the movie. The real unfairness here is not in Tarantino’s portrayal of the star but in the fact that, as matters stands, Chinese audiences won’t be given the chance to make up their own mind about it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks