Can Keir Starmer really be called a socialist?

From firm firebrands to Christian socialists, Labour leaders have redefined themselves in line with the times, says Sean O’Grady

As if they couldn’t think of anything more interesting to ask the leader of the Labour Party during an election campaign, Keir Starmer has been tackled on the hot topic of socialism, and whether he is a true socialist. Surprisingly, given his track record, Starmer immediately agreed that he was – though his answer was given a generous garnish of progressivism.

“Yes, I would describe myself as a socialist,” he said. “I describe myself as a progressive. I’d describe myself as somebody who always puts the country first and party second.”

It is a little disconcerting because he has dumped many of the socialist pledges he made when campaigning for the Labour leadership, and has ruthlessly expunged the Corbynite left of the party. As Private Eye editor Ian Hislop might say: if he’s a socialist, I’m a banana.

While the socialism of Jeremy Corbyn (now an ex-member of the party) was a constant source of debate and downright scaremongering during his leadership, Starmer’s declaration of born-again faith in the s-word has attracted surprisingly little attention.

So, is Starmer really a socialist?

He served in Corbyn’s shadow cabinet and wanted him in Downing Street but he also oversaw Corbyn’s expulsion from the party and trashed most of his policies. In any case, Starmer self-identifies as a socialist, so that should be good enough for everyone, shouldn’t it?

What about his values?

On the whole, he is to the left of the Tories – and even to the left of some of his predecessors, in terms of social outlook if not economic detail. But you can never be quite sure, for example, whether Starmer would extend state ownership of the utilities or freeze tax thresholds. Tony Blair could be said to share Starmer’s general outlook of economic efficiency married with social justice, but the former PM was regarded as a social conservative and an enthusiast for free markets.

Harold Wilson, another election-winning Labour leader, declared his party was “redefining and restating” its socialism in terms of the scientific revolution that was to frame, in white-hot fashion, the 1960s. It was a neat way of escaping from the existential debates about socialism that distracted the party during the Gaitskell era, while lending the party a modern image.

Is the Labour Party socialist?

Yes, because it still regards itself as such in its constitution and it’s still left-wing enough to qualify for membership of various international socialist bodies. The “new” Clause IV dates back to 1995 and replaced an older commitment to nationalisation that had become a political deadweight exploited by Tories. It was thus modernised: “The Labour Party is a democratic socialist Party. It believes that by the strength of our common endeavour we achieve more than we achieve alone, so as to create for each of us the means to realise our true potential and for all of us a community in which power, wealth and opportunity are in the hands of the many not the few; where the rights we enjoy reflect the duties we owe and where we live together freely, in a spirit of solidarity, tolerance and respect.”

Contrast that classic New Labour-speak with the romantic grandeur of the original 1918 version: “To secure for the workers by hand or by brain the full fruits of their industry and the most equitable distribution thereof that may be possible upon the basis of the common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange, and the best obtainable system of popular administration and control of each industry or service.”

In any case, it is a long time since a Labour Party general election manifesto made the bold claim put to the British people in 1945: “Labour Party is a socialist party, and proud of it. Its ultimate purpose at home is the establishment of the socialist commonwealth of Great Britain – free, democratic, efficient, progressive, public-spirited, its material resources organised in the service of the British people.” That was during the last time we had a July election, and it went down well with an electorate disillusioned with the Conservatives.

What is a democratic socialist?

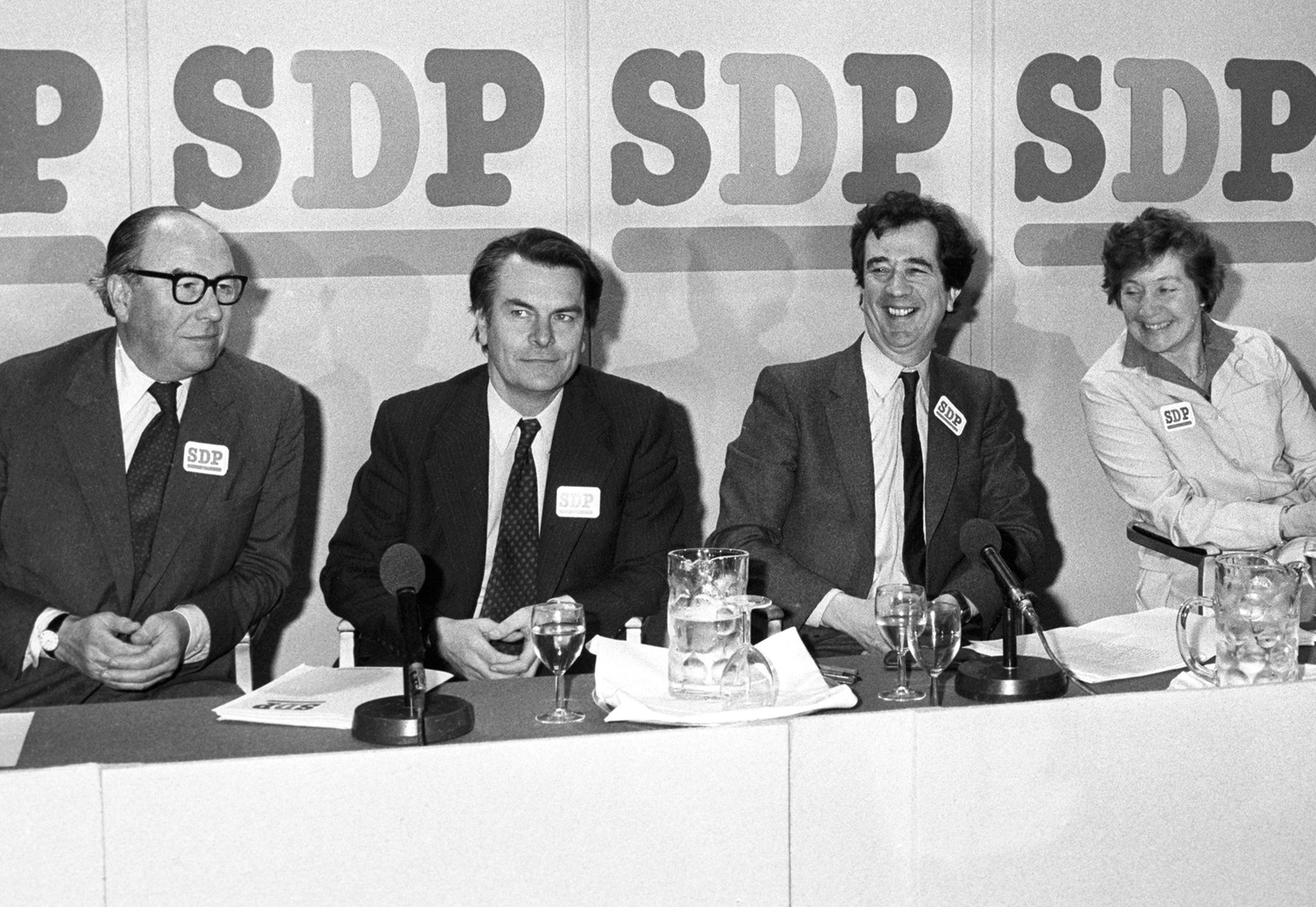

This was the formulation adopted by many in Labour in the 1980s after the breakaway Social Democratic Party (SDP) had appropriated the term “social democrat”. Leaders Neil Kinnock and Roy Hattersley came up with “democratic socialist” as an alternative to the more electorally divisive “socialist” and the label eventually found its way into the constitution. Their successors, John Smith and Tony Blair, also described themselves as “Christian socialists” as did many other prominent figures then (Jack Straw, David Blunkett) and now (Chris Bryant, Jonathan Reynolds).

Few Labour politicians have ever gone so far, or been so candid, as Roy Jenkins did in the early 1980s, when the s-word was being dropped with tedious frequency by the likes of Tony Benn and Jeremy Corbyn. Asked if he was a socialist, Jenkins replied with Olympian disdain that he had “not used the word socialist, or socialism, for some years”. Of course, Jenkins was by then a social democrat, and closer to being a Liberal. Despite everything, it’s probably not fair to conclude the same about Starmer, the progressive socialist.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments