Machiavelli: The grubby world of day-to-day politics

Our series continues with the Renaissance political scientist, Niccolò Machiavelli, whose name is still used to invoke cunning and unscrupulous behaviour

Niccolò Machiavelli (1469–1527) is probably the world’s best-known political scientist. His fame is such that his name functions as an adjective to denote cunning and unscrupulous behaviour devised to attain a particular end.

To describe a politician as Machiavellian is to suggest that their lack of moral sensibility renders them unsuitable for public office. However, it is also to grant them a certain grudging respect; Machiavellian behaviour is associated with a particular kind of cool, calculating intelligence.

Born in Florence, Machiavelli came to prominence as a young diplomat. He secured his position as head of the Florentine republic’s second chancery in 1498 at the age of 29. It was the custom in Florence for people occupying government positions to have had a strong grounding in the humanities. Machiavelli was no exception; his father, a keen scholar, had ensured that the young Niccolò was educated in the best traditions of Renaissance humanism.

The time which Machiavelli spent as a diplomat was essential to the development of his thought. Particularly, his ideas about effective leadership were rooted in a first-hand knowledge of the strengths and weaknesses of some of the major political figures of his age. Indeed, in his most famous work, The Prince, he made full use of a range of examples drawn from the real world and in doing so, set himself apart from nearly all his predecessors. Machiavelli was interested in the grubby world of day-to-day politics.

Diplomatic education

The lessons he learnt as a diplomat began almost immediately. In 1500, he was dispatched to the court of Louis XII of France to discuss the problems which had occurred when Florence, despite help from France, had failed to subdue Pisa, a rebellious city-state which at one time had been under Florentine control. The mission was beset with problems from the start. Though Machiavelli had little respect for the King of France, he was shocked to discover just how little the French thought of Florence. His native city was considered feeble and irresolute, lacking both the military and financial power to make an impact in foreign affairs. This was something which Machiavelli was never to forget; serious politics requires strength, fortitude and the capacity to act quickly and decisively.

There is such a gap between how one lives and how one ought to live that anyone who abandons what is done for what ought to be done learns his ruin rather than his preservation

This was hammered home to him shortly afterwards by the activities of Cesare Borgia, who notoriously employed a ruthless cunning to extend the scope of his power after he had been made Duke of Romagna by his father Alexander VI. Machiavelli, who spent some time in the company of Borgia, clearly admired the way that he dealt with his enemies. In The Prince, for example, he relates with approval how Borgia used deception in order to lure the leaders of the Orsini, a faction which had been plotting against him, to the town of Sinigaglia, where he promptly murdered them all. Machiavelli leaves us in no doubt that he thinks that Borgia had many of the skills required for leadership:

I believe I am correct in proposing that he be imitated by all those who have risen to power through Fortune and with the arms of others. Because he, possessing great courage and noble intentions could not have conducted himself in any other manner … Anyone, therefore, who determines it necessary in his newly acquired principality to protect himself from his enemies, to win friends, to conquer either by force or by fraud, to make himself loved and feared by the people … that person cannot find more recent examples than this man’s deeds. (The Prince, Chapter 7)

However, despite Borgia’s undoubted talents, his power did not last long. Mainly, this was a matter of bad luck but Machiavelli does criticise him in The Prince for helping Cardinal Giuliano della Rovere to become Pope Julius II, even though he had every reason to suspect that Rovere would not be favourably inclined towards him once he gained the papacy. In Machiavelli’s view, Borgia relied too heavily upon his own self-confidence and upon the continuation of the good fortune he had enjoyed earlier in his career. In the end, this was the cause of his downfall; political leaders need to be able to temper their personality in the face of the particular situations they confront and, ultimately, Cesare Borgia was lacking in this ability.

Machiavelli’s diplomatic career, while providing him with the experience he needed to write The Prince, came to an unfortunate end in 1512. He was dismissed from his post late that year after the Medici family, having come to power in Florence, dissolved the republic. To make matters worse, a few months later he was wrongly accused of plotting against the new Medicean government and then tortured and imprisoned. It was out of this turn of events that he came to write The Prince.

After he was released, he needed a way to ingratiate himself with the new Medici rulers. The Prince, the book which secured his reputation, was an attempt to show that he had abilities and knowledge which might be useful to a new ruler. The book’s dedication says it all: Niccolò Machiavelli to Lorenzo de’ Medici, the Magnificent.

The Prince

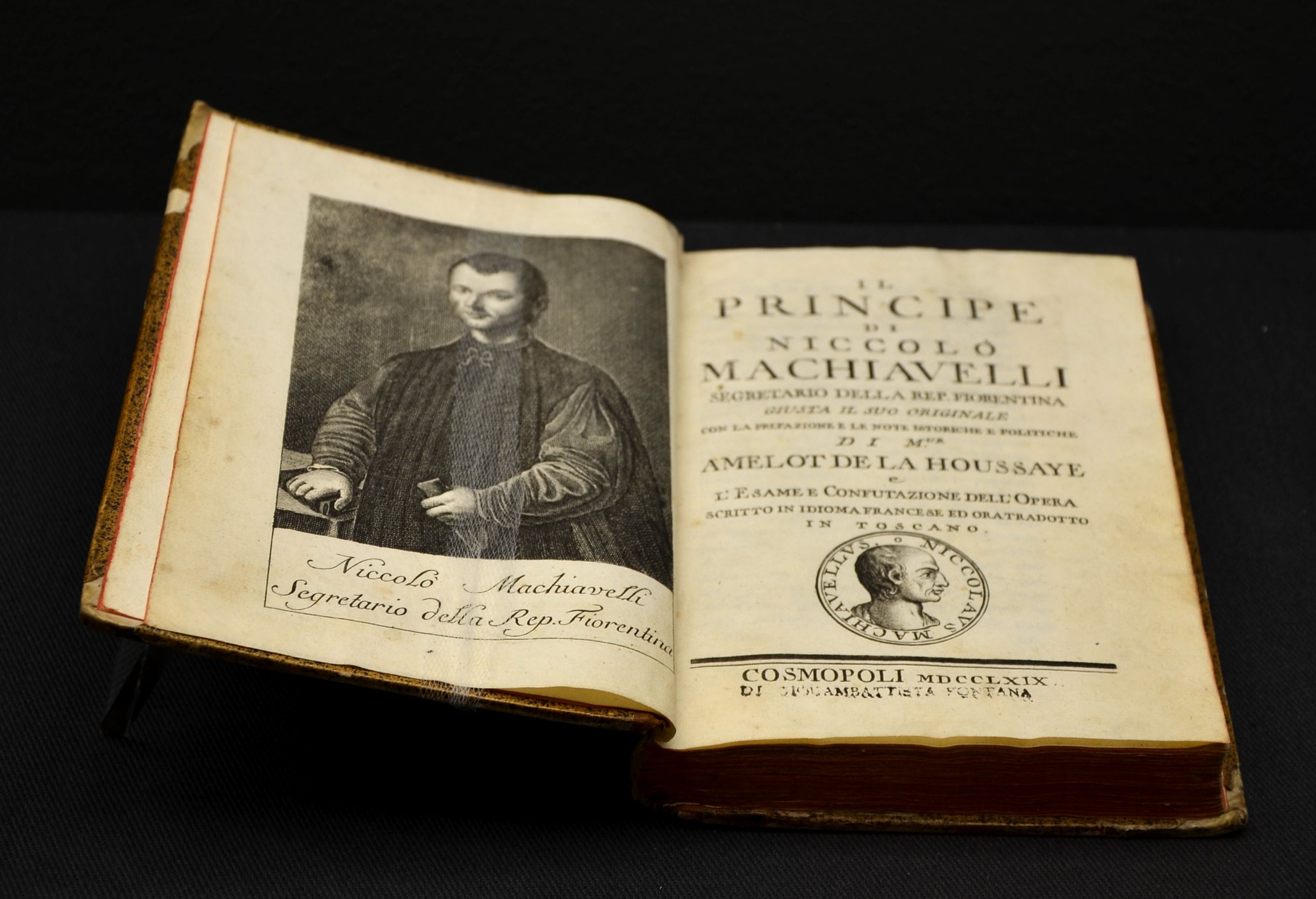

The book is primarily an essay on the art of leadership. It was first published in 1532, seven years after the death of Machiavelli, and it was initially well received. However, it fairly quickly gained a certain notoriety for its suggestion that leaders should set aside moral considerations when making political decisions. Indeed, Machiavelli is considered by many to be an amoralist; that is, to have no interest in whether leaders behave morally, only in whether they are able to secure and retain political power and glory.

There is certainly an element of truth in this characterisation of Machiavelli’s philosophy. For example, he completely rejects the traditional conception – as outlined in Cicero’s De Officiis, for example – which holds that the rational person, in order to achieve honour and glory, will always choose to act virtuously:

…there is such a gap between how one lives and how one ought to live that anyone who abandons what is done for what ought to be done learns his ruin rather than his preservation: for a man who wishes to make a vocation of being good at all times will come to ruin among so many who are not good. “Hence it is necessary for a prince who wishes to maintain his position to learn how not to be good, and to use this knowledge or not to use it according to necessity. (The Prince, Chapter 15).

This idea that leaders must learn how not to be good in order to rule effectively is rooted in a jaundiced view of the nature of human beings. Machiavelli thought that people were, “ungrateful, fickle, simulators and deceivers, avoiders of danger, greedy for gain” (The Prince, Chapter 17). As a result, certain styles of leadership just do not work. For example, Machiavelli argues that the prince who bases his power entirely on the love which the people apparently have for him is likely to be deserted when the going gets tough:

…men are less hesitant about harming someone who makes himself loved than one who makes himself feared because love is held together by a chain of obligation which, since men are a sorry lot, is broken on every occasion in which their own self-interest is concerned; but fear is held together by a dread of punishment which will never abandon you.

There is then something right about the accusation that Machiavelli’s ideas about leadership are predicated on a certain kind of amorality. However, this is not the whole story, for it is also the case that Machiavelli thought that effective leadership would often have good outcomes for everybody. For example, when considering whether it is better for a prince to rule by mercy or cruelty, Machiavelli argued that the excessively merciful prince, by tolerating disorder, will often bring greater harm to a community than the cruel prince who creates harmony through fear. Similarly, he noted that generosity in a leader will almost inevitably result in discord among the populace, because in the end, the prince who is predisposed to lavish displays of spending will have to tax the people in order to pay for them and will be resented and disliked as a result.

The measure of a leader

There is also a more general way that Machiavelli avoids the charge of amoralism. It was his view that a leader should strive for the goals of honour and glory. Indeed, it is a measure of a prince’s Virtú (pride, bravery, skill, forcefulness and an amount of ruthlessness) that he is willing to do whatever is necessary in the face of unpredictable fortune to achieve this end. However, in Machiavelli’s eyes, this does not justify cruelty for cruelty’s sake; such behaviour might bring great power but it will not bring honour and glory:

History, in equal measure, celebrates and condemns Machiavelli as the man who claimed that leaders need the strength of a lion and the cunning of a fox

Well used are those cruelties … that are carried out in a single stroke, done out of necessity to protect oneself, and are not continued but instead converted into the greatest possible benefits for the subjects. Badly used are those cruelties which, although being few at the outset, grow with the passing of time instead of disappearing. (The Prince, Chapter 8)

Machiavelli’s hope that The Prince would propel him back into public life did not come to anything. Indeed, shortly after its completion at the end of 1513, he came to recognise that his career as a diplomat was over, and, increasingly, he reinvented himself as a man of letters. In the remaining years of his life, he became more and more sympathetic to the case for republican government. Indeed, his most famous text of this period, Discourses on the First Ten (books) of Titus Livy, is a defence of republican government which takes ancient Rome as its exemplary model. In many ways, Discourses is the most sophisticated of his works. However, it is not what Machiavelli is destined to be remembered for writing. Rather, history, in equal measure, celebrates and condemns Machiavelli as the man who claimed that leaders need the strength of a lion and the cunning of a fox.

Major works

Niccoló Machiavelli only published two significant philosophical works, The Prince and Discourses. However, interested readers might wish to have a look at Art of War and his collected letters.

The Prince (1532)

Machiavelli’s most famous work is an incisive analysis on the art of leadership. It is argued that it is the primary duty of political leaders to secure and maintain power and that it is necessary for them to set aside moral considerations when pursuing strategies to this end. It is this book which bequeathed the term “Machiavellian” to posterity.

The Discourses (1531)

In some ways Machiavelli’s most sophisticated work, Discourses on the First Ten (books) of Titus Livy is a defence of the principles of republican government, which takes ancient Rome as it exemplar.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks