Jeff Bezos’s space adventure is a sign that the time for a wealth tax has come

Amazon’s boss has spent a bit of his $186bn of wealth on a space trip, but thousands of people don’t want him back. The super-rich must beware a backlash, writes Phil Thornton

What will historians call this epoch when they look back at the incredible wealth generation of the early 20th century? The Gilded Age captured the Victorian era’s entrepreneurial energy, and the Roaring Twenties the kind of reckless financial gambling seen in The Great Gatsby.

Leaving aside unsavoury monikers such as the Plague Age, perhaps the Catapult Era captures the combination of the vast leap in wealth achieved by a select few and the way they spent some of said wealth.

Jeff Bezos, the founder of online retail giant Amazon, who was recently declared the second-richest person in the world, has decided to spend some of his estimated $186bn on the first human space flight, to be launched by his company Blue Origin next month. One as-yet-unnamed astronaut won an auction for a seat on the flight with a $28m bid.

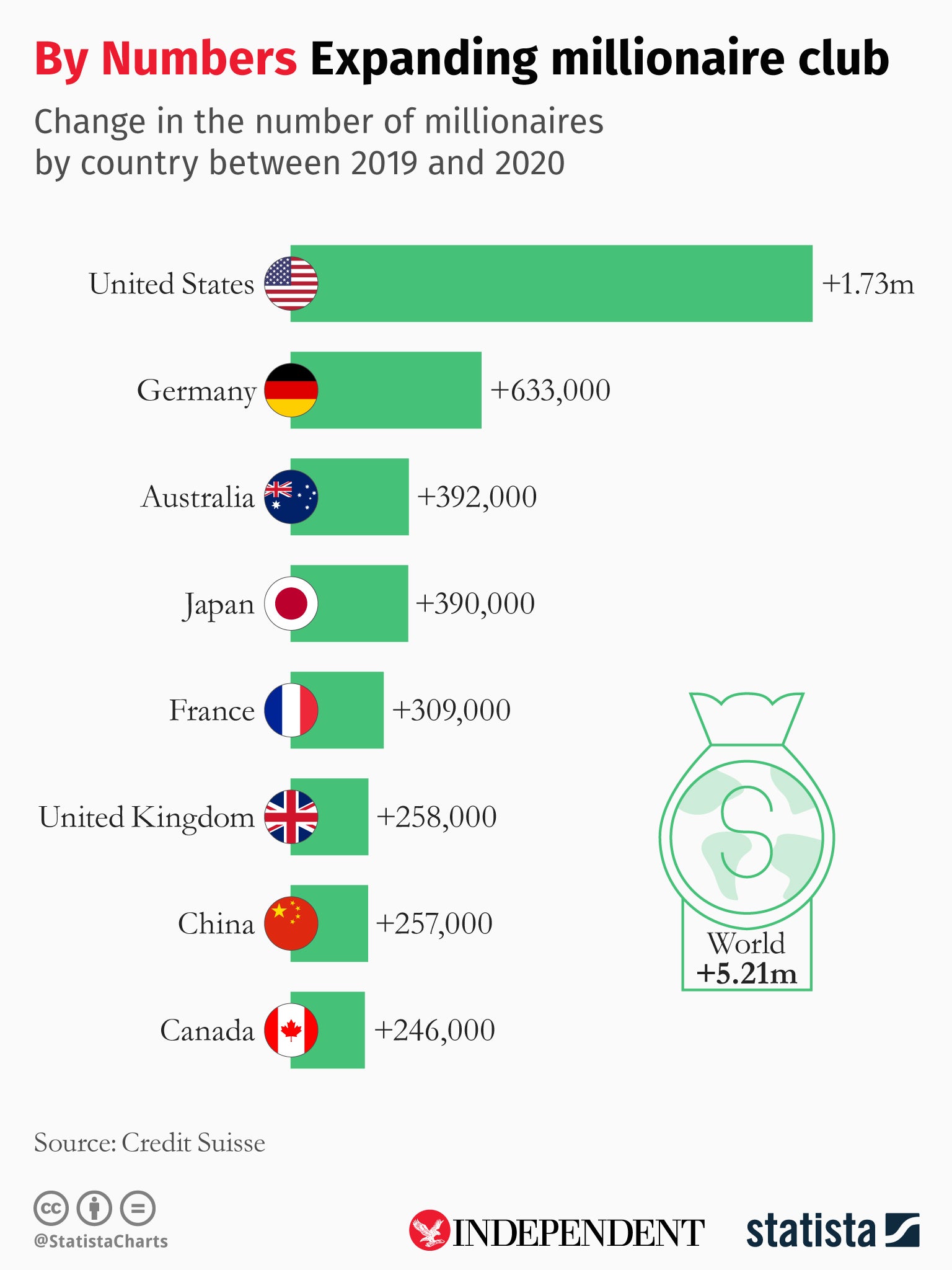

Bezos is not alone in his affluence. The other household-name billionaires, such as Bill Gates, Warren Buffett, Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg, have been joined by more than 5 million new millionaires. Last week’s report by Credit Suisse bank showed that 5.2 million people joined their ranks during 2020, despite the devastating impact of the coronavirus pandemic on many people’s jobs and incomes.

In fact, the stimulus measures taken by governments to counteract the impact of the virus helped drive up the price of assets such as property and shares, which tend to be held by the wealthy, building on gains seen in the wake of measures put in place to offset the 2008-09 global financial crisis.

As Credit Suisse puts it, wealth creation in 2020 appears to have been “completely detached from the economic woes resulting from Covid-19”.

While the pandemic has added a painful twist to the story, the world appears to be at the peak of a wealth cycle that has played out in the past.

The industrial revolution in the 19th century led to vast wealth creation on both sides of the Atlantic, especially during the Gilded Age of John D Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie. The Roaring Twenties was the time of the motor car; of Henry Ford and Alfred Sloan.

Both eras came to a halt. The First World War played a role in ending the Victorian excesses, and the Wall Street crash and great depression brought the Roaring Twenties to a halt.

But economic policy intervention also played a role. The anti-trust legislation in the US at the turn of the 20th century broke up some of the corporate behemoths. The social contract in Europe after the Second World War ushered in an era of greater equality, economic stability, and less visible wealth generation. As the Trades Union Congress remarked in a 2008 report into the super-rich, in 1953 one Inland Revenue official claimed there were only 36 UK millionaires left, down from over 1,000 before the Second World War. There are now 2.5 million, according to Credit Suisse.

In his detailed analysis of the rise in inequality in the UK, the late economist Sir Anthony Atkinson always maintained that high levels of inequality are not inevitable, and that policies can be designed to make our societies both more equitable and more efficient. As he told me in an interview in 2015, there are ways for governments to redistribute wealth and reduce inequality that are good for growth and good for the economy, and there are ways that are bad. “You have to choose the right ones, and, if you do, there isn’t necessarily a conflict,” he explained.

There is talk about making tech companies pay more tax, but that is unlikely to have a major impact. One solid route would be a wealth tax, which was considered but shelved in the 1970s. The rise in inequality, along with the huge government debts taken out to pay for the costs of the pandemic, has given new wings to the idea and earned it support from the World Bank among others. Although chancellor Rishi Sunak ruled it out in the Commons last year, the idea was given strong backing by the Wealth Tax Commission, an academic-led investigation that was endorsed by former cabinet secretary Lord (Gus) O’Donnell.

A well-designed one-off wealth tax would raise a total of £260bn at a rate of 5 per cent over £500,000 per individual, or £80bn at a rate of 5 per cent over £2m per individual, payable at 1 per cent per year over five years, it found.

As Lord O’Donnell points out, a one-off tax on banks was introduced by the Conservatives under Thatcher, and another, on privatised utilities, by Labour under Blair. In both cases they were motivated by the specific circumstances of the time, so neither had wider economic repercussions.

While recent episodes of inequality have been defused without violence, revolution can be a consequence – as King Louis XVI might testify. So far, public antipathy towards the super-rich is only playful: around 22,000 people have signed a petition calling for Bezos to be denied re-entry to Earth.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

1Comments