Six ways the coronavirus pandemic threatens to worsen inequality in the UK

Analysis: The pandemic is interacting with and exacerbating the UK’s many inequalities. The public policy challenge of unwinding them will be massive, writes Ben Chu

Inequality was a major political flashpoint before the coronavirus even arrived on the UK’s shores.

But the pandemic has now forced problems of inequality even further up the political agenda thanks to its grossly uneven impact on different parts of society.

The health impact of Covid-19 and the economic impact of the lockdown has not only exposed existing inequalities of income, gender, education, ethnicity, region and age, but is also threatening to make them worse.

Here The Independent looks at the evidence on how the pandemic is interacting with and exacerbating UK inequalities and highlights the scale of the public policy challenge in unwinding them when this is over.

1. Income

Income inequality dramatically rose in the UK in the 1980s as a direct result of the economic revolution instigated by the Thatcher government.

On a broad measure, income inequality remained elevated level for the next 30 years.

The lockdown also hit an unequal UK labour market, both in terms of pay and conditions, with fast growth in recent years in casual work and the use of zero-hour contracts.

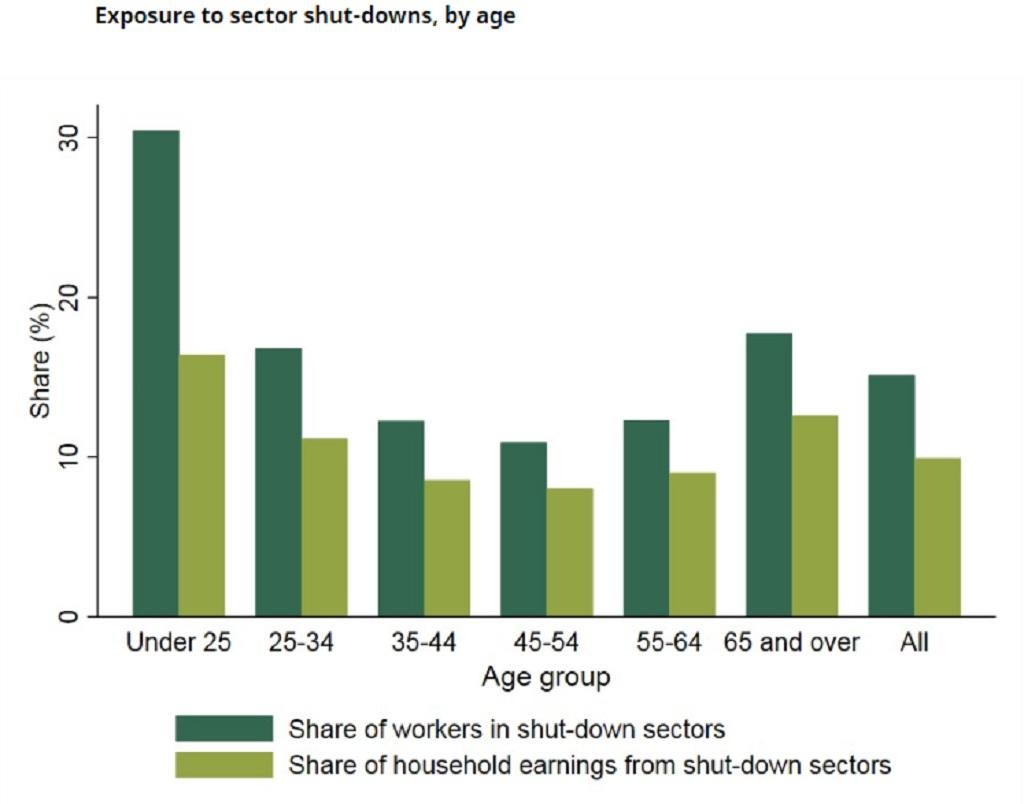

Research from the Institute for Fiscal Studies shows that more than 30 per cent of people in the bottom tenth of the earnings distribution are in sectors that have been forced to shut down.

Survey data also confirms that those on lower incomes have, unsurprisingly, much lower emergency savings, which means that they are less well placed to cope with the sudden loss of income.

The government’s furlough scheme, covering almost 9 million jobs, will have helped to support many of those incomes.

And for those who have lost their jobs, the chancellor increased universal credit payments in the March Budget. Yet even after this increase the UK’s unemployment benefits for single people will remain lower than many European schemes in terms of the amount of an average worker’s income that gets replaced.

To prevent income inequality rising still further as a result of this crisis the government is likely to need to, at least, maintain that increase in jobless benefits.

In the longer term, economists argue that it will require higher spending on things like training and retraining with the spending funded by a more progressive taxation system.

2. Age

Young people have been relatively unscathed by the virus from a health perspective, but they have been disproportionately hit by the economic impact.

Separate IFS research shows that workers under the age of 25 are twice as likely to work in a shutdown sector than older groups.

Young people graduating from university or leaving school are also likely to be entering a brutally tough jobs market, with high unemployment and widespread economic dislocation.

Those who have graduated in previous recessions have suffered life-long hits to the earnings over their lifetimes.

Analysts are urging a focus on fixing the UK’s broken apprenticeships system and more public investment in green infrastructure (things like retrofitting millions of homes with insulation and electric boilers to reduce carbon emissions) to provide jobs for younger people.

3. Gender

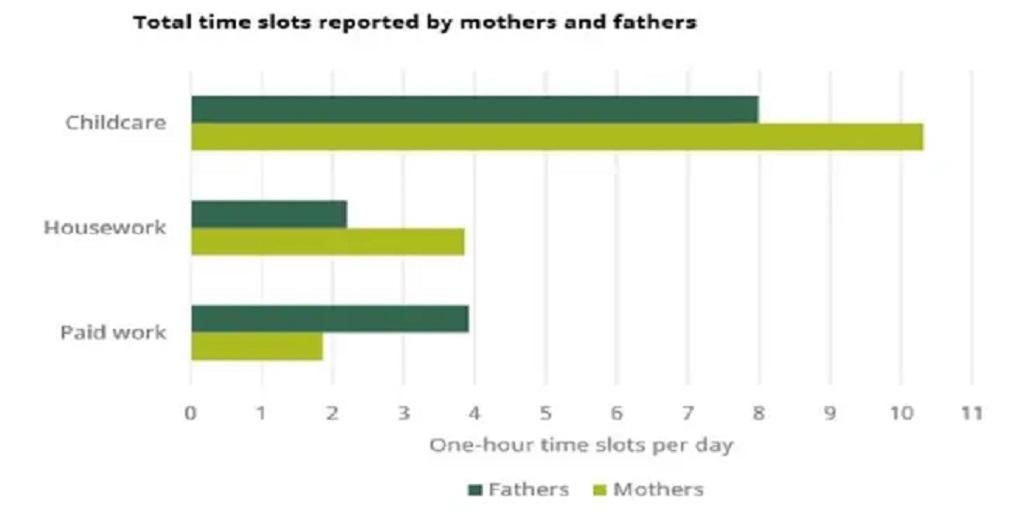

Lockdown household survey evidence from the IFS also shows that mothers are more likely than fathers to have lost their jobs or to have seen their working hours cut.

And those that have retained their formal work are more likely to be doing a larger share of childcare and housework than their male partners.

And women were about one-third more likely to work in a sector that is now shut down than men.

The fear is that the disruption to many mothers’ jobs will further impede their career development and exacerbate the gender pay gap.

The policy prescription advocated by activists and economists remains a reform of workplace culture to place a higher value on childcare and to allow flexible working and also greater transparency over employees’ pay to expose discrimination.

4. Education

Experts are concerned about the negative impact of the school closures on the education of children in more disadvantaged households.

There was a big gap here already and it’s likely to have increased in the shutdown.

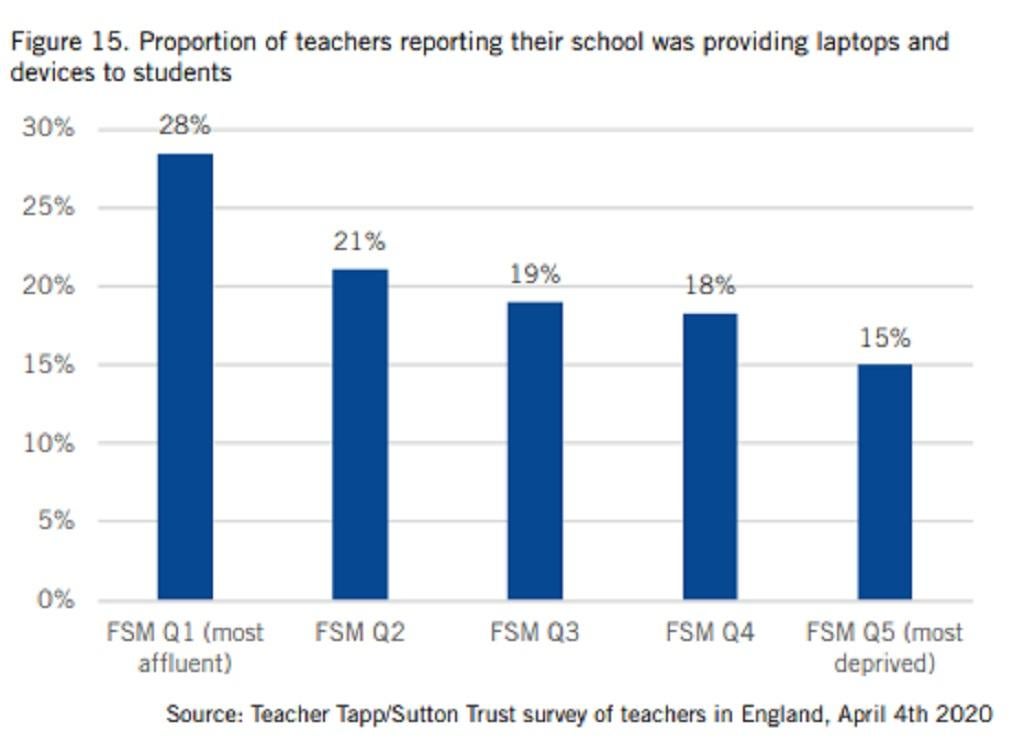

The Sutton Trust has found that 60 per cent of private schools and 37 per cent of state schools in the most affluent areas already had an online platform in place to receive work, compared to 23 per cent of the most deprived schools.

Schools serving richer families were more likely to be providing technology to their children to facilitate home learning.

A government-commissioned report by the Education Endowment Foundation has warned that a decade of progress in reducing the attainment gap between disadvantaged children and their peers could be wiped out due to the schools shutdown.

Analysts are urging a specific focus on these children as schools reopen, possibly by extra classes over the summer holiday or more intensive tuition in class.

There will likely be pressure for considerably more funding for schools serving more disadvantaged communities.

5. Ethnicity

The UK went into this pandemic with health and income inequalities by ethnicity.

And those health inequalities seem likely to have contributed to the higher Covid-19 mortality rate for black and some Asian people than white people shown by work by the Office for National Statistics.

That may also be related to the types of sectors that people work in. Black people are disproportionately represented in health and social care. For instance, black Africans make up 2.2 per cent of the working-age population but account for 7 per cent of all nurses.

Pakistani and Bangladeshi workers are also heavily concentrated in badly hit sectors such as taxi driving and restaurants.

Activists and campaigners argue these ethnic inequalities in part reflect structural racism in many UK institutions and the jobs market – something that needs to be urgently tackled

6. Regions

The big regional gap in the UK before the pandemic was been between London and the rest of the UK.

This was the inequality that drove the government’s “levelling up” agenda.

From a health perspective London has been hit much hard than other regions, with a considerably higher death toll in the capital than anywhere else.

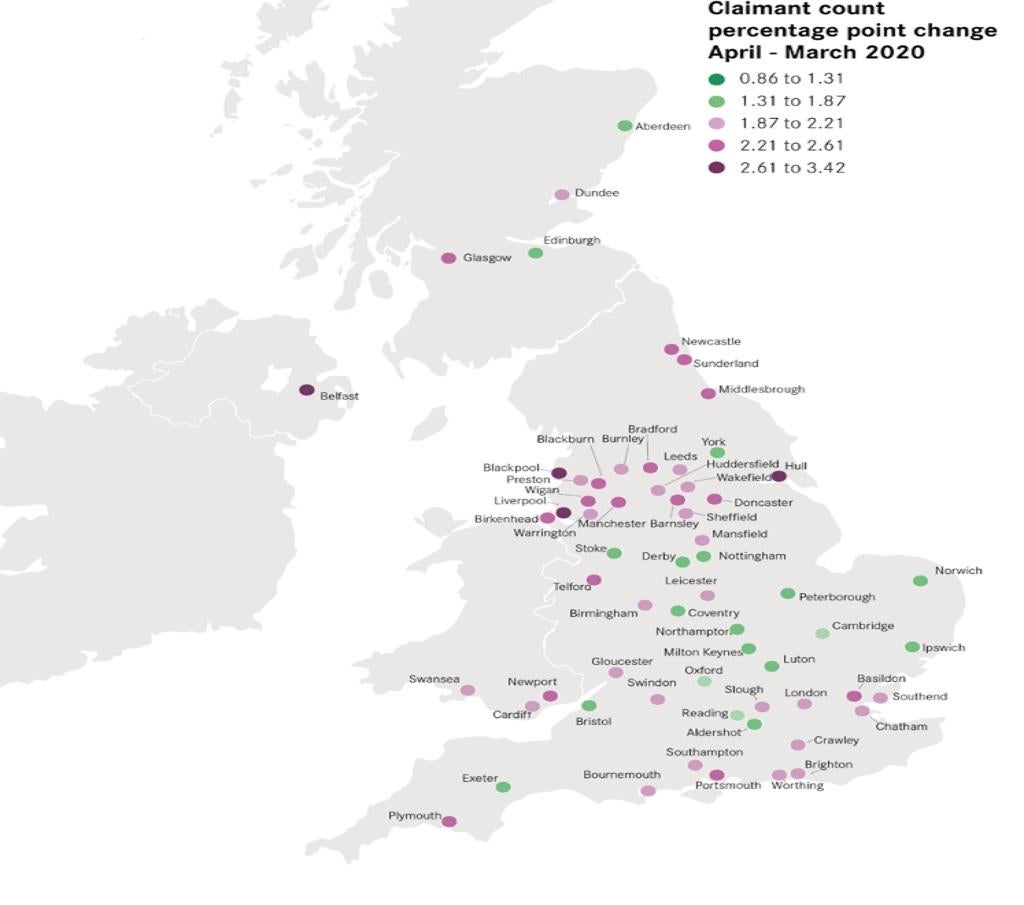

Yet economists fear it will be the UK’s regions, particularly in the North and Midlands, which could bear the economic brunt of the lockdown because they had weaker economies to begin with and, perhaps, because of their lower share of workers in industries where it is possible for employees to work from home.

Analysis by the Centre for Cities shows that cities in the north and midlands recorded the biggest increases in unemployment claimant counts in April.

The claimant count went up by 2 percentage points nationally, but by 3.44 percentage points in Blackpool, 2.86 in Liverpool and 2.84 in Hull.

Economists argue this uneven regional impact underscores the need for government policy to increase public investment in skills, research and infrastructure in less prosperous regions and also to devolve power to them too; in short to follow through on the levelling up agenda.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments