Should the government raise more money from capital gains tax?

Many think the chancellor has it in his sights. But what exactly is capital gains tax? How much more revenue could such a hike be expected to raise? And who would end up bearing the burden? Ben Chu looks at the numbers

The chancellor, Rishi Sunak, this week wrote to the government’s Office for Tax Simplification and asked the body to carry out a review of capital gains tax.

The Treasury has tried to downplay suggestions that this means it is set to rise.

Yet with public borrowing soaring as a result of the coronavirus emergency and the Treasury’s official watchdog, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), warning this week of a long-term structural deficit opening up in the public finances, many believe tax rises are inevitable after the crisis and see capital gains tax as a prime candidate for a levy that will – or should – increase.

But what exactly is capital gains tax? How much more revenue could such a hike be expected to raise? And who would end up bearing the burden?

What is capital gains tax?

It is a levy tax imposed on capital gains, which means the profits someone gets from disposing of an asset for more than it was worth when they acquired it.

So, for example, if someone buys shares in a company for £100 and then sells those shares for £300 a few years later, the difference between the two prices – £200 – represents their capital gains.

That sum is liable for capital gains tax. The share of your capital gains you are required to pay in tax depends on a host of factors and there are also a number of reliefs.

Gains eligible for “entrepreneurs’ relief” (recently renamed “Business Asset Disposal Relief”) are subject to a rate of just 10 per cent.

But the most salient fact is that the tax rate anyone pays on capital gains will be lower than the equivalent rate they would pay if they received those gains as regular income.

The tax is paid by individuals and trusts (which look after assets on behalf of individuals), though not by companies.

How much does it raise?

Before the current crisis the OBR was expecting capital gains tax to bring in around £9bn for the Exchequer in 2019-20.

That’s around 1 per cent of all tax revenues and 0.4 per cent of GDP.

Since the tax is levied on transactions in assets whose price can and does fluctuate, the same is true for the tax take.

For the past two decades the capital gains tax take has bounced between a low of 0.1 per cent of GDP in 2002 and a high of 0.5 per cent just before the financial crisis.

Who actually gets capital gains?

Excluding the gains of trusts, the taxable and realised gains of individuals totalled £55bn in 2017-18, the latest year for which full HMRC data is available.

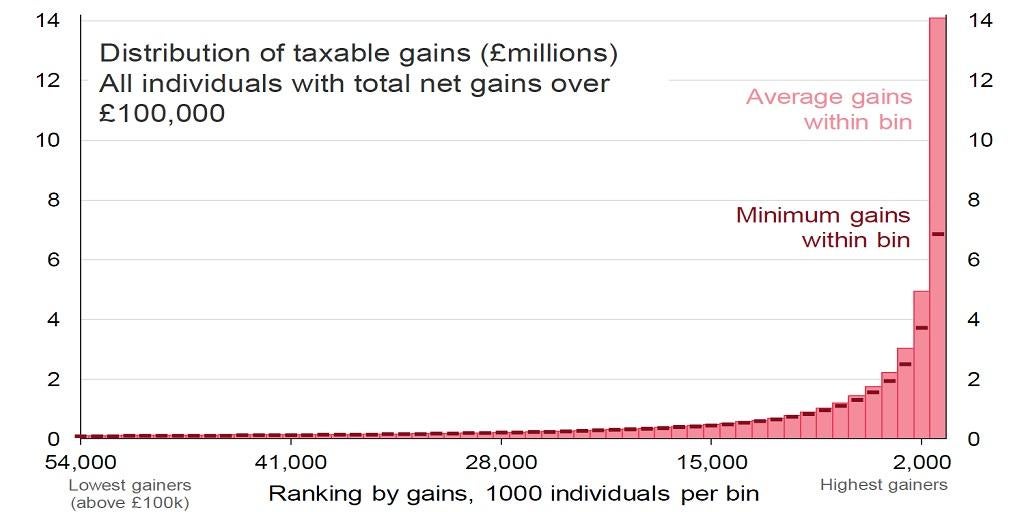

And recent research by Arun Advani of Warwick University, Andy Summers of the London School of Economics and Adam Corlett of the Resolution Foundation showed that these gains are concentrated among a relatively small group.

The £55bn was spread across 260,000 individuals, giving them an average gain of £210,000 each.

Moreover, 62 per cent of the total went to just 9,000 people who each realised over £1m in gains.

Is this about housing?

A great deal of the UK’s household wealth is tied up in homes

Yet an individual’s primary residence is not currently subject to capital gains tax when they sell it.

Landlords and second home owners are subject to capital gains, but property is a relatively minor part of the picture.

Most of the realised gains are now from the sale of non-listed shares.

The biggest recipients of capital gains are increasingly financiers, particularly partners in private equity firms, who receive the bulk of their remuneration in the form of capital gains (called “carried interest”) rather than income.

Why are capital gains rates lower than income tax?

A big part of the answer is that successive governments have bought into the idea, pushed by lobbyists and business owners, that lower rates of tax on capital gains encourage investment and entrepreneurship, which boost national prosperity and create jobs.

The evidence, however, does not tend to support this theory.

And many experts think the lower tax rate on capital gains is now distorting the tax system, with a great deal of capital gains now “disguised income” to take advantage of the lower tax rate.

The charge is that it is exacerbating income and wealth inequality.

So what would tax reform look like?

Many argue that the capital gains tax should be raised to be in line with marginal income tax rates, with higher earners paying a higher tax rate.

This would, in theory, raise the tax take and – because capital gains mainly flow to the rich – reduce inequality too.

Yet it’s hard to be certain how much extra revenue raising the rates would raise because people’s behaviour would probably change. Financiers and business owners might re-structure their affairs and reduce their taxable capital gains.

The IPPR think tank estimated last year that putting up capital gains tax rates to income tax rates (though not including main home sale profits in the tax base) would raise up to £130bn of additional revenue over five years, though it saw this declining to £90bn after behavioural changes.

Much would depend on whether the various reliefs were abolished too.

Some wealthy people make far higher use of reliefs than others as separate work by Advani and Summers has shown.

Taking this into account, they propose a new Alternative Minimum Tax, which would require everyone earning more than £100,000 to pay at least a 35 per cent tax rate on their income plus any capital gains.

They estimate that this could raise around £11bn a year in additional tax.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments