Are schools really responsible for driving the spread of coronavirus?

How strong is the evidence that schools are a major cause of the spread of this virus? Ben Chu investigates

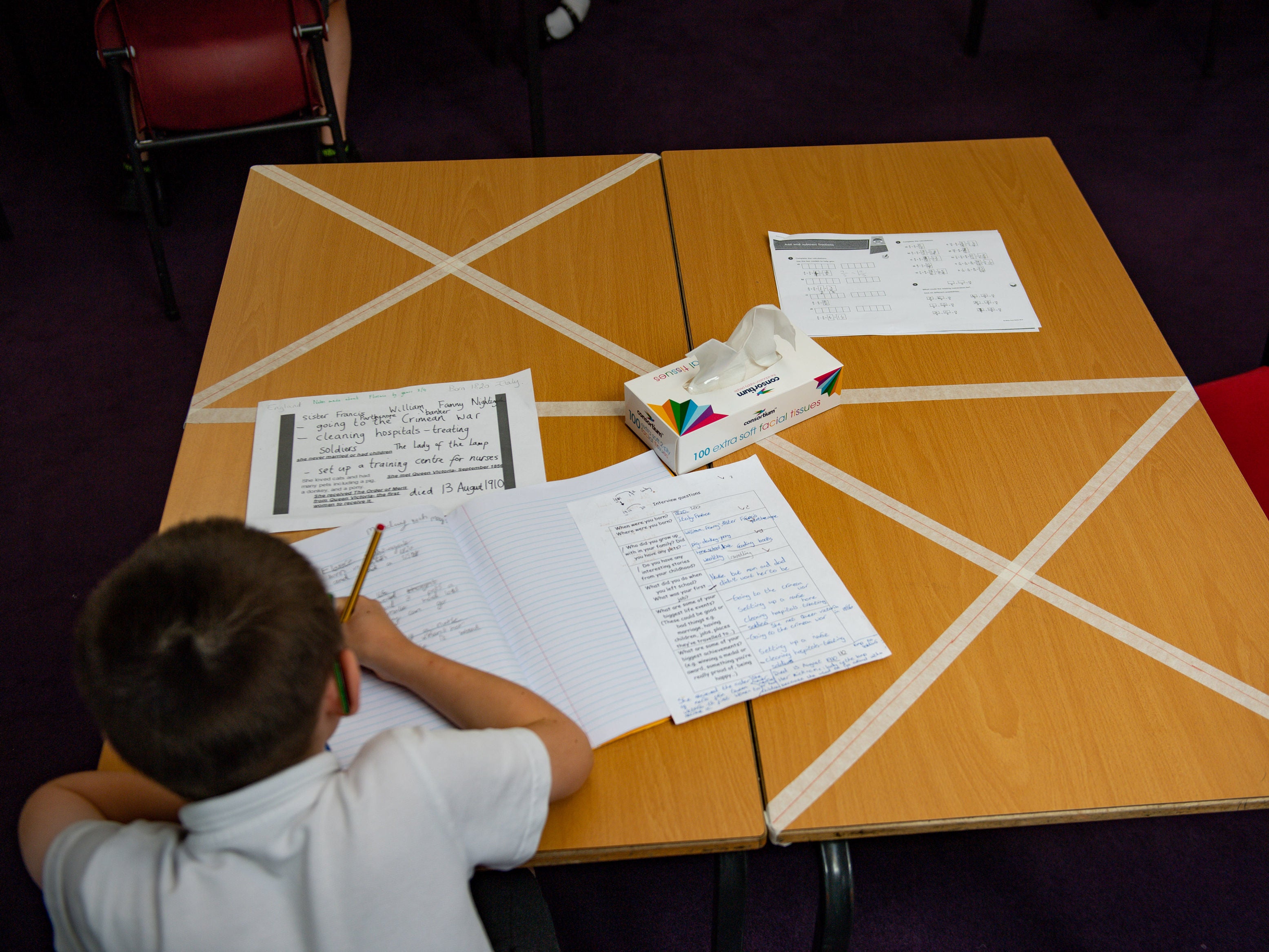

Ministers have bowed to pressure from scientists and teaching unions to delay the return to the classroom for secondary school children (and some primary school children) in England.

"The evidence about the new Covid variant and rising infection rates have required some immediate adjustment to our plans for the new term," education secretary, Gavin Williamson, told the Commons on Wednesday afternoon.

But how strong is the evidence that schools are a major cause of the virus spreading?

The basic facts are not disputed. The Office for National Statistics’ large-scale random weekly survey (released on 24 December) shows that rates in the run-up to Christmas were considerably higher for children than adults.

The ONS estimates that on 18 December the positivity rate for children between year 7 and 11 (ages 11 to 15) was around 3 per cent, according to the sample group tested.

For age 2 to school year 6 pupils (age two to 10) the rate was 2 per cent – while the rate for those age 50 and over was below 1 per cent.

Moreover, the positivity rate for school age children has been rising fast this month.

The Real-time Assessment of Community Transmission study (React) at Imperial College London has also been showing a similar picture in England.

The latest round of the monthly survey, published on 15 December, found that between 13 November and 3 December the national prevalence of the virus was around 0.94 per cent across the population.

But for ages 13 to 17 the prevalence was more than double that at 2.1 per cent, while for ages 5 to 12 it was 1.7 per cent.

The researchers think the evidence does suggest schools are driving transmission of the virus.

They point out that infections appeared to increase more in the second national lockdown in November compared to the first in the spring, when schools were required to close.

One of the lead authors of the report, Professor Paul Elliott of Imperial College, has noted that the mixing of school-age children has corresponded to increased spread, particularly in London.

A modelling study released by researchers at the London School of Tropical Hygiene and Medicine (LSHTM) on 23 December takes as its assumption that children mixing in schools are indeed spreading the virus.

The authors conclude that unless the government closes primary and secondary schools as well as universities the reproduction number of the virus – the average number of other people infected by each infected person – will not fall below 1 and the outbreak will continue to worsen.

It has been reported that Sir Patrick Vallance, the government’s chief scientific adviser, has told ministers that school closures will be needed to get the disease under control. We haven’t seen the details of their advice but it’s likely to be based on work similar to that done by LSHTM.

Yet how secure is the modelling assumption that schools have been accelerating the spread of the virus?

As well as its national survey, the ONS also conducts a specific testing study of English schools, working with Public Health England and LSHTM.

Between 3 November 2020 and 19 November 2020 this study found around 1.24 per cent of pupils and 1.29 per cent of staff tested positive.

On 17 December Dr Shamez Ladhani, a PHE consultant epidemiologist who oversees the study, said the proportion of schoolchildren and teachers with coronavirus “closely mirrors” the proportion in the local community.

The share of pupils and teachers testing positive for the virus in November was higher in areas with higher prevalence – suggesting that the causality might run from the latter to the former.

Dr Ladhani argues it’s possible that the virus was being brought into schools several times from outside, rather than being spread by transmission between pupils.

“We know that there is infection happening in school-age children. What we don’t know is the dynamics of that infection – whether it is occurring in school, or outside schools or at home,” he said.

Mike Tildesley, a professor at the University of Warwick and a member of the government’s advisory group on pandemic modelling, told The Independent that there was evidence that the virus was spreading in schools, particularly secondary schools.

“But it’s not clear that the spread is disproportionate to the spread in the surrounding community,” he added.

“There has been some suggestion schools are driving the increase … in these high incidence regions. I don’t necessarily think there’s strong evidence if that’s the case. My fear is that schools end up taking all the blame for this.”

So, given all this uncertainty, can we say the government has made the right decision to delay the return to school?

There are other harms from closing schools to take into consideration, such as disruption to children’s education, exam preparations and mental health.

There are also knock-on economic impacts if parents are unable to work because they are looking after children.

The rate of infection among students and staff attending school closely mirrors what’s happening outside the school gates.

Some other European countries, notably France, have been able to reduce infection growth since November while keeping their schools open.

However, Germany and the Netherlands felt they had no choice but to close theirs earlier this month.

Another consideration is how the delay links with other policies, such as introducing testing in schools.

“The idea of maybe a slight delay of secondary school children going back to school to allow mass testing to get into place I could cautiously support because there’s a viable alternative [to closure]," says Professor Tildesley.

On the evidence question, it’s worth noting that the evidence against school transmission in the UK is also somewhat hazy at the moment.

The authors of the ONS schools study concede that the results of the first round were based on a sample size that was “relatively small”, covering just 105 schools (63 secondary and 42 primary).

And the fact that during the November lockdown cases rose in schools in London while they declined in the rest of the capital might add weight to the argument that schools are themselves responsible for transmission.

The danger of waiting for more conclusive data before closing schools is that the disease could accelerate very rapidly if it is being driven by them.

And on the question of damage to education, it’s important to bear in mind that if schools are kept open and the disease worsens they are likely to be closed anyway and might need to be closed for longer.

As with handling the disease more generally, the essential argument in favour of acting decisively and early in closing schools is that, in the medium term, it might be the best way to protect the education of children.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks