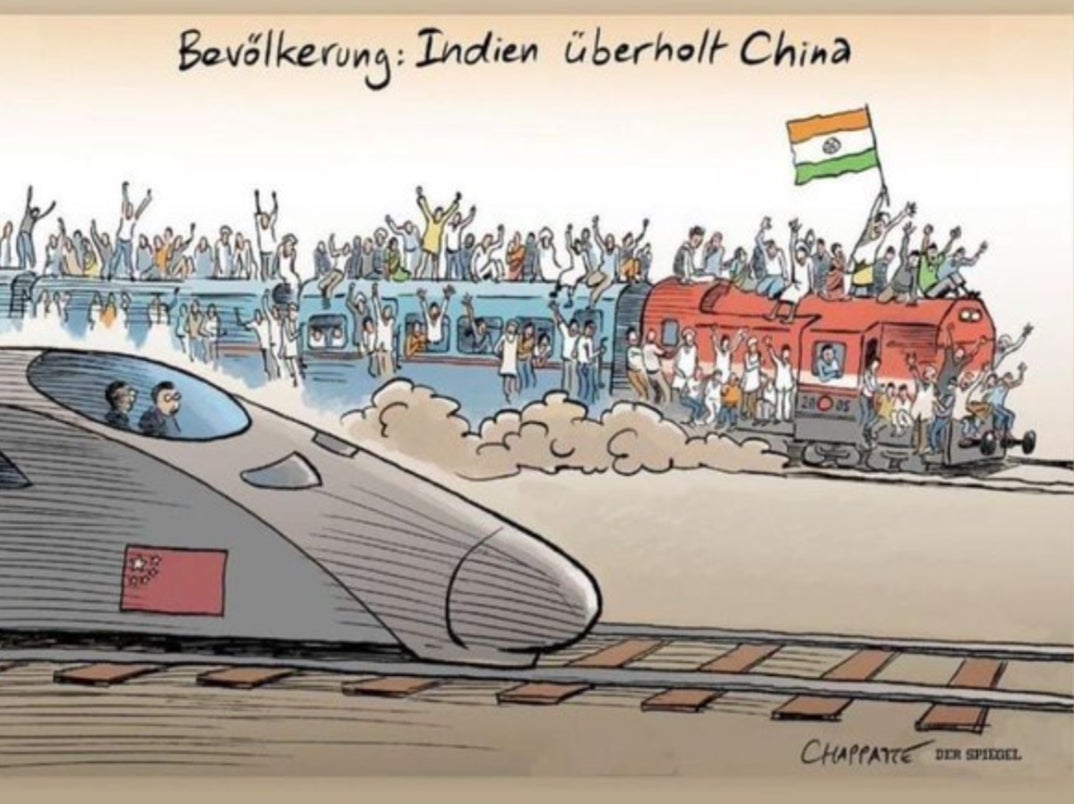

Should India really be celebrating as its population overtakes China?

The jury is out on whether India can successfully exploit its demographic dividend, reports Sravasti Dasgupta

India is overtaking China as the world’s most populous country, the UN said this week – but experts are split on whether the milestone is worth celebrating.

There are doubts about whether the world’s largest democracy can reap its demographic dividend and match the economic trajectory of its neighbouring nuclear superpower.

From conducting business with Russia as it invades Ukraine and attempting to placate the West as well as presiding over the Group of 20 nations, India has risen to become an important geopolitical decision-maker.

Latest population estimates from the UN’s Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA) show India will shortly reach, match, and then surpass that of China.

DESA estimates India will have 1,425,775,850 inhabitants – roughly the same figure as China’s peak population last year.

“Projections indicate that the size of the Chinese population could drop below one billion before the end of the century,” it said. “By contrast, India’s population is expected to continue growing for several decades.”

However, the timing is unclear. While the UN recommends countries conduct a census every decade, India has not had one since 2011; its 2021 census was postponed due to the Covid pandemic and the next count is expected in 2024.

John Wilmoth, director of population for the UN, said the exact moment India will surpass China “isn’t known, and it will never be known”.

India seizes Chinese advantage

Observers in India say the change is a window of opportunity for India to repeat China’s success.

SY Quraishi, former chief election commissioner of India, and the author of The Population Myth: Islam, Family Planning and Politics in India, says the change has been on the cards for two decades.

“It is neither a shock for India nor a surprise and it is a happy development because, being the most populous country in the world along with being the largest democracy, make India very distinctive,” he tells The Independent.

China’s rise to superpower status was because its population was treated as a human resource, according to Mr Quraishi.

“China, from being an extremely poor and backward country, became a superpower only because of its population which made it economically strong,” he says.

“The same advantage has come to India. We have a larger working population than China. Their population is getting older while India is the youngest country with a median age of 28 years against China’s 39.”

Poonam Muttreja, executive director of non-profit Population Foundation of India, says the country’s large young population has a “huge potential to contribute to the national economy and the country’s development”.

Ms Muttreja tells The Independent that while statistics show India’s population has “already slowed down considerably”, it is expected to grow due to its large, young population.

“Between 2001-11, India’s population grew by around 18 per cent, which was lower than the growth rate for the previous decade (around 22 per cent).

“The latest National Family Health Survey data says India’s total fertility rate for 2019-21 had already reached the replacement level. However, India’s population will grow because of the population momentum – a result of a large young population of 365 million.”

According to DESA in 2022, China had one of the world’s lowest fertility rates (1.2 births per woman). India’s current fertility rate (2.0 births per woman) is just below the “replacement” threshold of 2.1, the level needed for population stabilisation in the long run in the absence of migration.

Experts have cautioned against family planning measures in India despite its growing population. Unlike China, which adopted its one-child policy from 1980-2015, India’s population has stabilised without any coercive measures, say Mr Quraishi and Ms Muttreja.

“India is the first country in the world to have [a] national family planning programme and, unlike China, it has been based on education and motivation with no compulsion,” Mr Quraishi says.

“China’s compulsory one-child norm has proved counterproductive in the long run.”

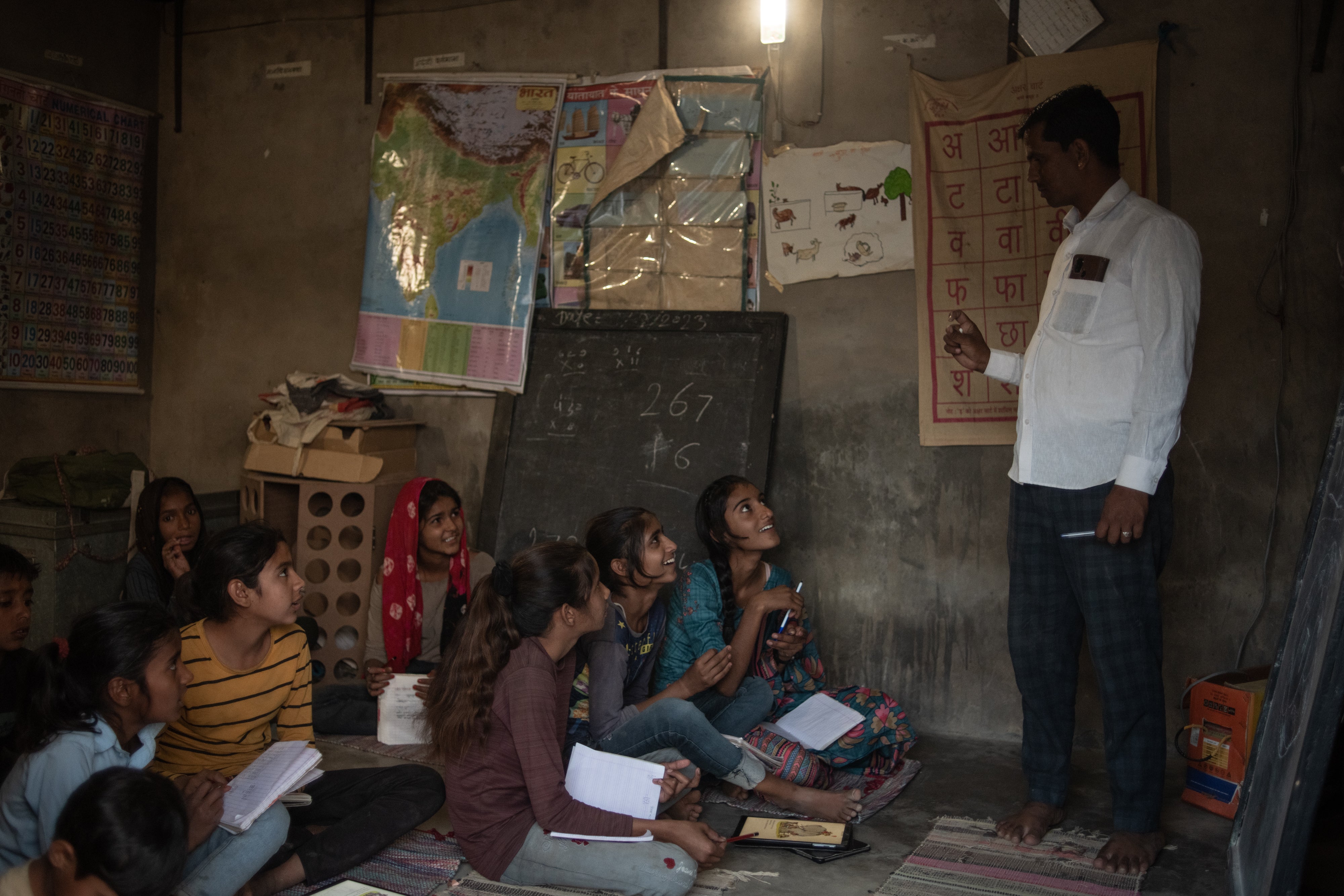

However, economists say India will only be able to replicate China’s economic success if it invests in health, education and jobs generation.

Santosh Mehrotra, a visiting professor at the University of Bath’s Centre for Development Studies, says India can replicate China’s growth only by matching its other developments. “But we don’t seem to be doing that,” he tells The Independent.

“We are 20-25 years behind China and we don’t have the luxury of 20-25 years because we will be running out of our demographic dividend by mid-2030 and we will also become like them an ageing society.”

Demographic dividends can be summarised as the economic gains of having a larger working-age population than a non-working one. The United Nations Population Fund estimates the start of the working age to be 15 years and the non-working age to be below 15 and above 65 years.

Mr Mehrotra says India’s demographic dividend began in the 1980s and will end in 2030s.

“Our labour force participation rate is in the region of 40 per cent. In China, it is 60 per cent and the average in the world is 60 per cent. The major reason is that women in our country are not joining the labour force and this is because we are not creating non-farm jobs.”

Legacy of colonial rule

Economists say India has much deeper problems than China.

“In the first 30 years after independence, they invested in health and education,” he adds. “We did not, even though both countries became independent around the same time. We are still not investing in health. That is the tragedy.”

Mr Mehrotra says the lack of expenditure on health was seen during the Covid pandemic when a devastating second wave brought India’s largely public funded health infrastructure to the brink of collapse.

And unlike China, he says, India did not invest in education even after 40 years of independence.

“We inherited from the British colonisers a literacy rate of 18 per cent and life expectancy was 32 per cent in 1951,” Mr Mehrotra says.

“You would expect that they would invest in school education and girls’ education which brings down the birth rate. But we only sharply increased our investment in school and girls education in the 90s and followed up with the Right to Education.”

Mr Mehrotra is referring to the 2010 law that aims to provide free and compulsory elementary education to children between ages six and 14.

Government expenditure in India on early childhood education for children between ages three and six is a mere 0.1 per cent of the gross domestic product, according to a study jointly conducted by the Centre for Budget and Governance Accountability and commissioned by non-profit Save The Children, reported The Hindu.

The average spend per child is just ₹8,297 (approximately £81) per annum – a fourth of the desired levels.

Mr Mehrotra also points out that India’s land reforms were weaker in its first three decades of independence compared to China.

“When our growth was ready to take off in 1991 [when economic liberalisation reforms were implemented], we already had massive inequality on the basis of health education and land access. China’s focus on creating non-farm sector jobs along with health and education helped its economy’s growth.”

Population analysts have also stressed the need to focus on health and education to make use of India’s young population.

“But ... to do that, requires the country to make investments in their health, nutrition, education, skilling and employability speedily,” Ms Muttreja says.

“It is also important to ensure that girls and women benefit from efforts made in education and skilling. Data shows girls and women lag in education, employment, digital access and various other life-empowering parameters.”

Delimitation

Concerns have also been raised that India’s growing population will have an impact on its electoral democracy and require delimitation exercises to redraw constituencies on the basis of population.

In 2002, a freeze on delimitation of the Lok Sabha, the lower house of parliament, was enforced till 2026.

The national delimitation exercise has, however, raised concerns about the unequal representation of states in the Lok Sabha.

According to India’s Emerging Crisis of Representation, a study published for the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in 2019, if India’s Lok Sabha seats are redistributed across states after a delimitation exercise in 2026, then north Indian states may gain more than 32 seats, while southern Indian states may end up with approximately 24 fewer seats.

Mr Quraishi says delimitation cannot be allowed to disturb the state wise allocation of constituencies as this will amount to penalising southern states that have implemented family planning measures better than their northern counterparts.

“All MPs from the South [Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka and Kerala] together are 125, while Uttar Pradesh and Bihar alone have 125 seats. We cannot punish them for their good family planning,” he says.

Rationalisation of the size of the constituencies within the states can be done, he says.

“It may be recalled that in the Delimitation of 2006-07 we found a constituency (outer Delhi) which had 35 lakh (3500000) people while Chandni Chowk had 5 lakh (500,000) people which had to be balanced.”

“So within a state, demarcation must be done to make constituencies almost equal to each other.”

Most importantly, population experts say a national census is essential.

“Census is a very important planning tool for India as a large number of our public schemes are based on it. Since this data is more than a decade old, its relevance is limited,” says Ms Muttreja.

“I do hope the census survey is held soon so that India has current data to guide its programmes and policies.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks