The devil is in the detail with promises by McDonnell and Javid to boost public spending

Analysis: Specific spending promises have a habit of being undone, writes Sean O'Grady, and there are plenty of difficult challenges ahead

You might not realise it from the heated rhetoric about Joseph Stalin and Donald Trump, but the two main parties are going to take the British economy in a remarkably similar direction – as all the reputable think tanks such as the institute for Fiscal Studies and the Resolution Foundation agree. The British state will, by the middle 2020s, be rather larger than it is today, and the total national debt will little changed from where it stands now.

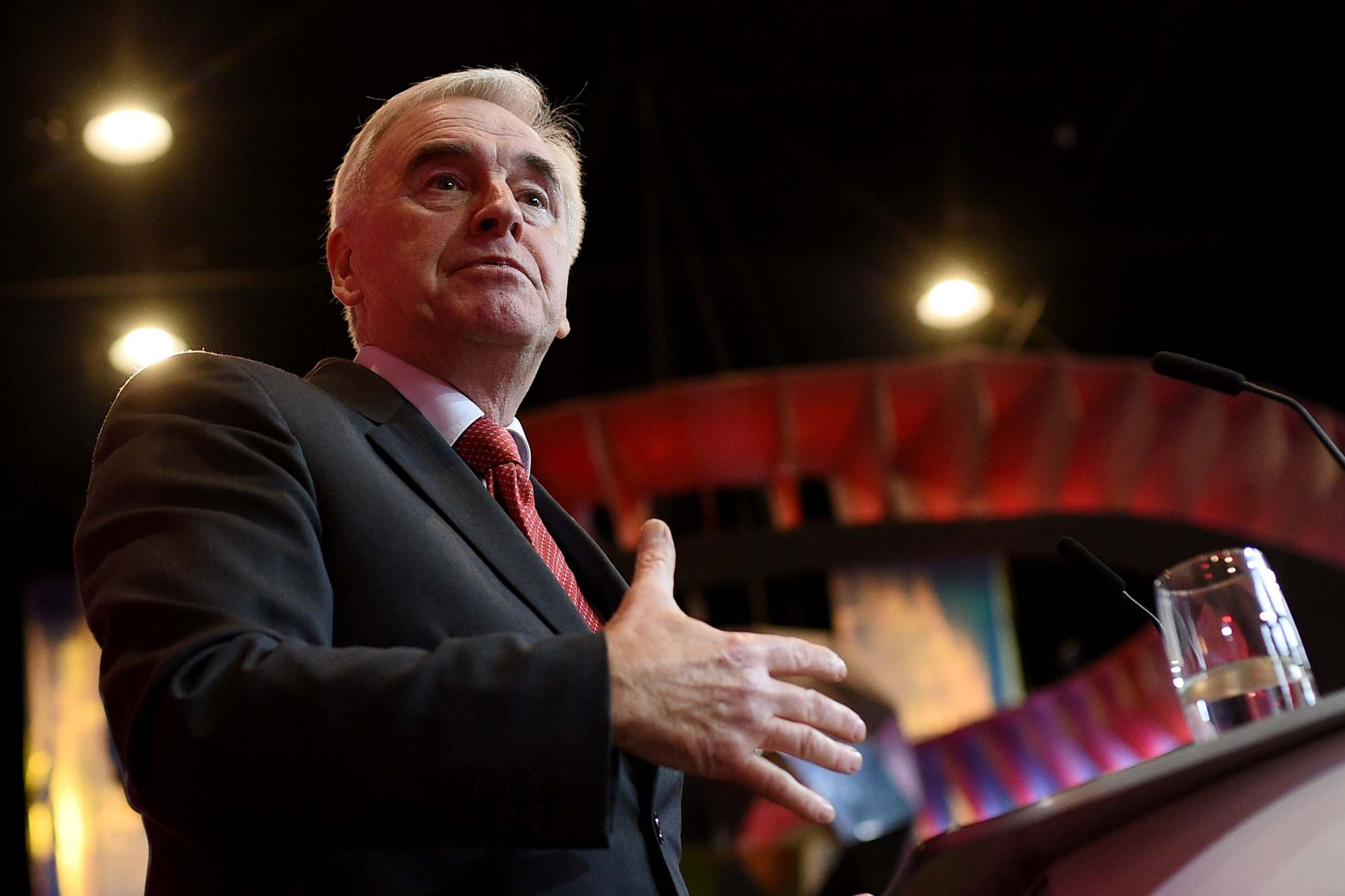

Both parties, for example, will revise the Treasury’s “fiscal rules” to mean that they have more freedom to borrow to invest. The Conservatives propose a new 3 per cent limit of GDP for such projects, against a smaller, vaguer current target. For Labour, shadow chancellor John McDonnell simply says that there will be no rule for borrowing to invest in national infrastructure.

Instead, Labour will operate a new measure which will account for the value of the state’s assets to balance the level of the state’s debt in acquiring and running those assets – “public net worth”. This will be a useful way to account for the cost of its £150bn Social Transformation Fund (over five years, building housing, care homes and upgrading schools and hospitals), the £250bn (over 10 years) Green Transformation Fund and the costs (unknown) of renationalising the Royal Mail, the railways and parts of the water and energy sectors. The £400bn-plus cost of these will be balanced by a £400bn increase in the value of the assets (more or less – depending on how they are valued).

In macroeconomic terms, for both parties, the benefit to the economy of, say, faster broadband and more efficient use of energy will help offset the costs – and will boost GDP. There remains the microeconomic questions around, for example, what will happen to electricity tariffs, council-house rents, rail fares, and so on. In other words, how far should the benefits of the policies pay back the costs, and how much can be left to the wider community through general taxation? Again, there are few specifics on this.

Provided the investment in everything from classrooms to roads is truly effective, and isn’t just blown in underused white-elephant schemes, then in principle the sums “add up” – as ever, provided markets are prepared to lend the money at an acceptable rate of interest. That, in turn, will depend on the UK retaining its credit ratings, and the confidence of investors in the UK’s ability to pay back its debts on time.

Aside from that, both parties are also committed to substantial increases in day-to-day or current spending. The government maintains that it is still committed to a balanced budget on this basis, allowing for the economic cycle (so borrowing naturally runs higher in a recession) – but is unclear about when precisely this happy state of affairs will materialise. McDonnell has basically the same policy. Both parties, though, are sure to spend more on everything from the probation service to the low wages in parts of the NHS (because of the living-wage hikes).

Where Labour and the Conservatives differ is on tax cuts, but in the absence of a Budget or, as yet, detailed proposals it is impossible to know what they really intend to do to raise money. Labour will opt to raise taxes for the top 5 per cent of earners – on around £80,000 a year and more. The Tories seem inclined to cut taxes right across the income range. Thus, other things being equal, the Tories would be borrowing more as a result, though they’d argue that tax cuts improve incentives and raise economic growth in the long run.

Either party, in fact, will boost the levels of state spending to levels not seen since the 1970s; about 43 to 45 per cent of GDP. Neither will they be doing very much to reduce the national debt by a significant amount – about 75 per cent of national income in total.

Of course much depends on Brexit, and the shape of the post-Brexit arrangements with the EU and other trading partners. Most economists belive that the UK will be worse off than it would be by remaining in the EU, and worse off under the Johnson plan for a free trade deal than under Labour’s putative scheme for a customs union with the EU. Even so, there remain great unknowns about migration levels, among many other variables. The slower economic growth, the greater the difficulty to delivering improvements in both private living standards and public services.

There are many other factors impossible to calculate. How, for example, would the independent Bank of England – under its existing, or a new, remit – react to supposedly excessive borrowing? If it put interest rates up to restrain inflation that would slow growth; if it did not it would mean a burst of inflation. How will sterling fare? An economic slowdown during a post-Brexit adjustment might mean a significant devaluation, again with inflationary effects and an impact on jobs and profits. It might trigger a return to austerity; an already high national debt would limit the government’s ability to respond to a banking crisis, say.

Then there is the wider global economy, vital for a trading nations such as Britain – the US-China trade war, for example, is something a UK government can do little to affect.

So the wise voter might well not take too much notice of the arguments in the coming weeks, and bear in mind that the general character and image of a party and its leaders can do more to reveal its intentions than any particular sentences in a manifesto, costed or otherwise. Events will, not for the first time, have a habit of undoing even the most sincere of political promises.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments