What lessons can we draw from the eurozone’s coronavirus recession?

What should we make of data showing that activity in the bloc fell by 12 per cent in the second quarter? Does it tell us anything we didn’t know already? And is the outlook for Europe better than elsewhere? Ben Chu reports

More information is rolling in that shows the colossal economic damage inflicted by the coronavirus pandemic and the public health measures imposed by governments around the world to contain the disease.

On Thursday Eurostat estimated that the eurozone economy contracted by 12 per cent in the second quarter of 2020, easily the biggest quarterly decline since the single currency zone came into existence. For the countries that make up the bloc it was probably the biggest economic slump since the 1930s.

But what should we make of this latest data? Does it tell us anything we didn’t know already?

The first thing to say is that though the information is inevitably shocking it is not particularly surprising. We knew that lockdowns had crushed economic activity on an unprecedented scale in many countries. Indeed, that was part of their purpose.

We also knew that parts of the eurozone – Spain and Italy in particular – had been hit exceptionally hard by the pandemic so it’s not surprising that the bloc overall has suffered.

The estimated damage to eurozone activity in the second quarter is in line with the 9.5 per cent drop in activity reported by statisticians in the US earlier this week.

The UK is expected to record a similar fall in activity for the second quarter, perhaps even larger.

That said, it’s also notable that economic pain of the eurozone has not been been evenly experienced. Over the first half of 2020 Germany’s output fell 12 per cent. In Spain the impact was twice as large, falling by almost a quarter.

One slight puzzle from the data is that Italy’s GDP did not fall by as much as Spain’s despite being subject to an extremely tight lockdown and a large number of coronavirus deaths.

One must bear in mind, though, that Italy never really recovered from the financial crisis. This coronavirus slump is merely the latest recession to hit the country in the past decade, albeit easily the largest.

The level of GDP in Italy is now, astonishingly, roughly where it was two and a half decades ago.

This eurozone data covers activity up until the end of June so it is backward-looking. What can we say about the outlook beyond then?

Economists are pessimistic about those countries that rely heavily on tourism. The travel sector contributes 14 per cent to GDP in Spain and 13 per cent in Italy.

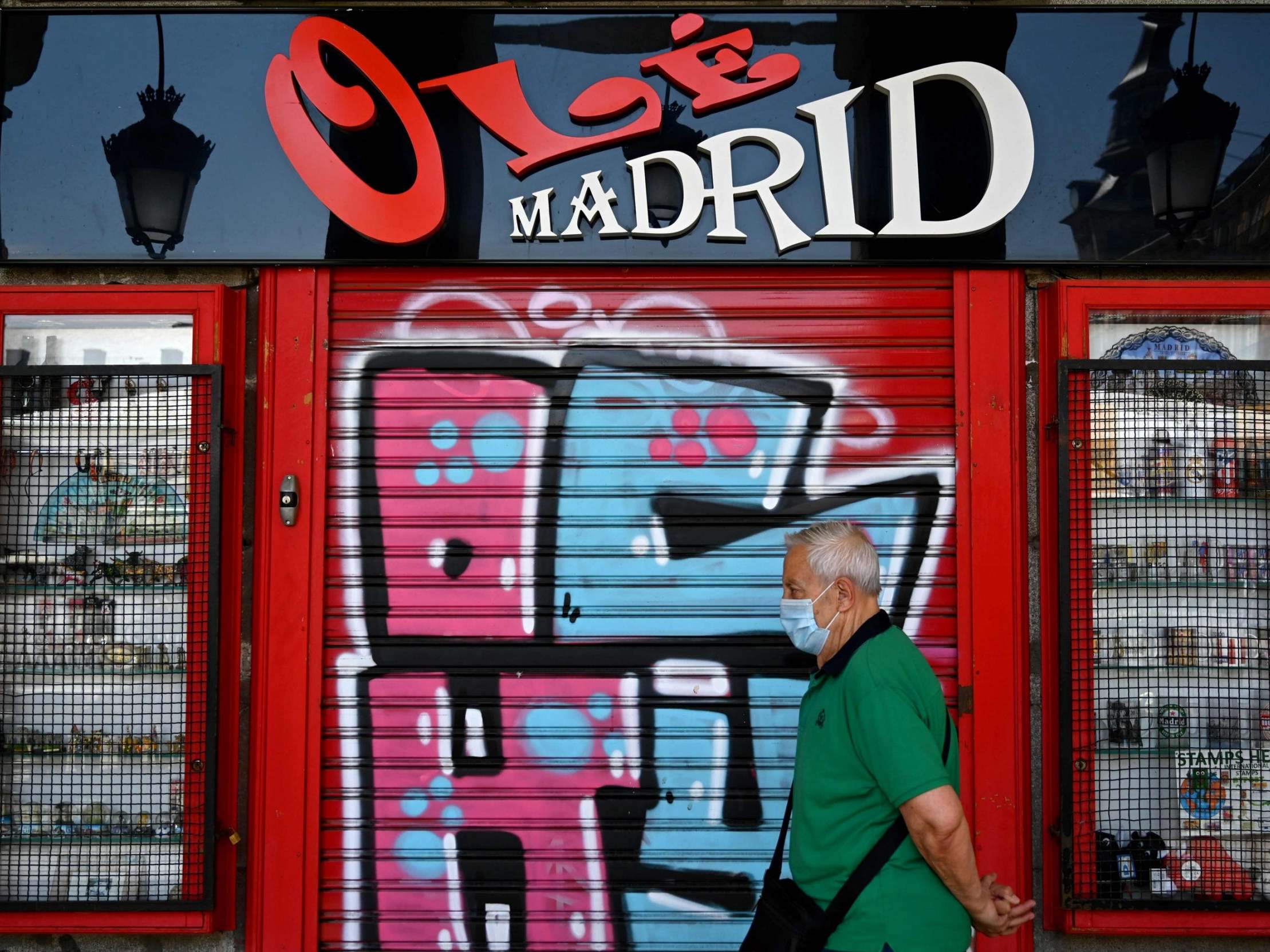

And Spain will almost certainly be suffering economically from the restrictions imposed in recent days on travellers by the UK and elsewhere in response to its jump in cases.

More broadly, various high-frequency economic indicators from across Europe – firm surveys, restaurant bookings, etc – point to a reasonable bounce back in the level of activity since lockdowns began to be eased in most European countries May.

Yet it’s very unclear how sustained this recovery will be, especially if there are future outbreaks that force a reimposition of restrictions. It’s hard to think of circumstances less likely to induce investment by European businesses.

And there’s unlikely to be much support from abroad in the form of exports. China seems to have recovered fairly well, but there are big doubts about the US economy in the wake of spikes in cases in several states.

The upshot is that few expect a strong European recovery in the coming months.

What can Europe do to help itself? The European Central Bank has, so far, been active in printing money in this crisis, despite fears a recent German constitutional court ruling could hamper its ability to underpin the currency.

And on 21 July the EU’s political leaders agreed a €750bn pandemic recovery fund, made up of grants and loans, with the money to be spent in the coming years, much of it in struggling economies like Italy and Spain.

That’s widely been seen as a landmark moment for EU unity because the money will be borrowed by the EU as whole.

Rob Wood, an analyst at Bank of America, wonders if the deal would ever have been done if Britain had been involved in the negotiations. “To some extent, this could be viewed as a positive consequence of Brexit for the EU,” he notes.

Yet Brexit-driven unity aside, the outlook for the European economy remains saturated in uncertainty and pessimism – very much in line with the rest of the developed world.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments