What might be the financial fallout of European Super League fiasco?

Short-term financial pain looms for the clubs that unsuccessfully attempted to set up their own league. But what are the longer term economic consequences of this week’s failed football revolution? Ben Chu investigates

The European Super League (ESL), born on Sunday and died on Tuesday, lived for just three days.

But the fallout from the debacle for the clubs involved could be severe and long lasting - and the impact on the economics of football itself just might be permanent.

The idea of a breakaway league has been around for decades – but the comments on Monday from Florentino Perez, the President of Real Madrid and the chair of the putative new league, made it clear that what had finally brought it into existence was the financial shock of the pandemic on clubs.

“We are doing this to save football at this critical moment,” he said. “We are all ruined.”

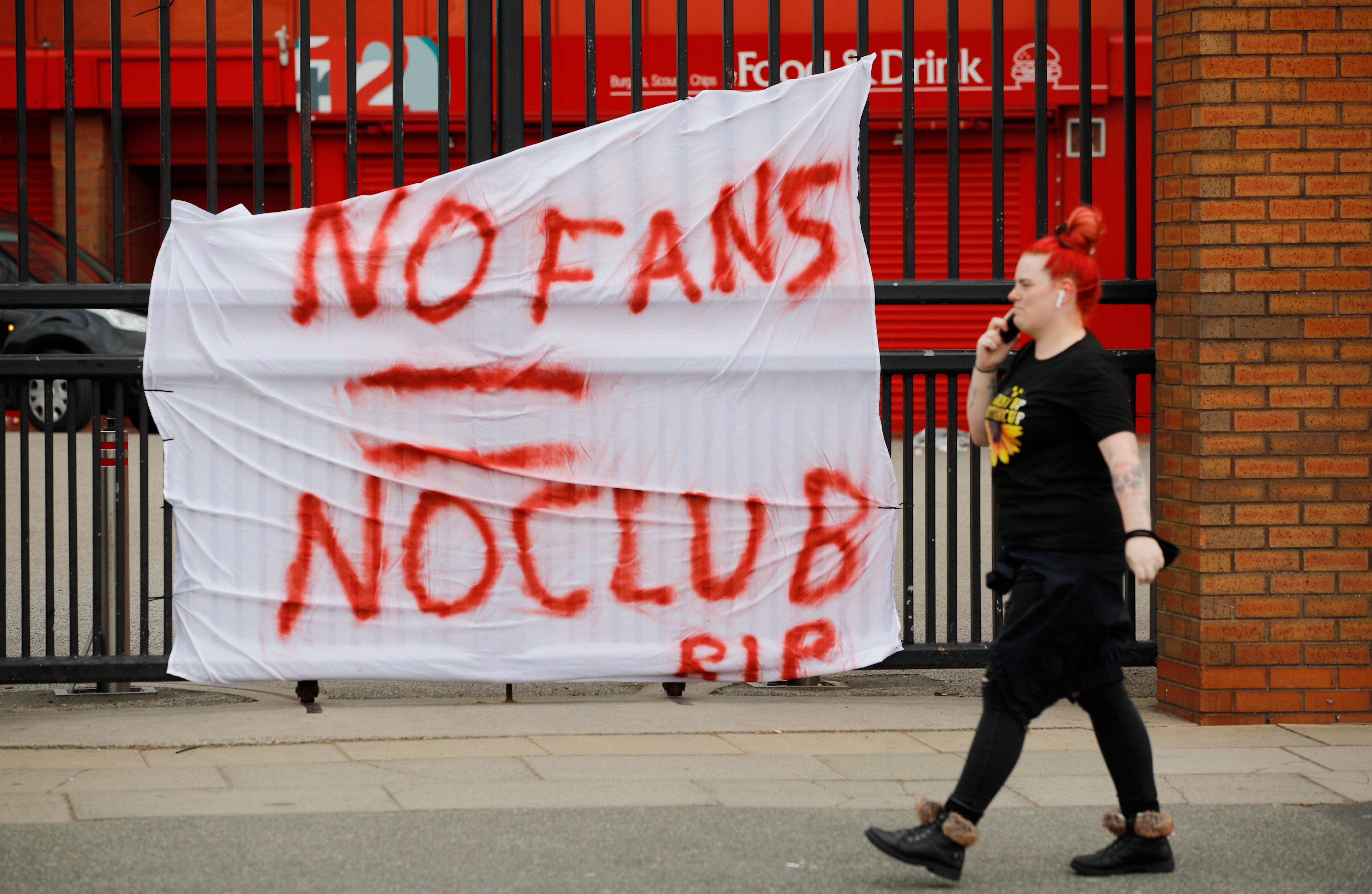

He was referring to the total wipeout of match revenues as games have had to be played in empty stadiums.

The accountancy firm Deloitte estimates that the top 20 clubs in Europe have missed out on over €2bn of revenue across the 2019/20 and 2020/21 season, with the 12 ESL clubs accounting for the lion’s share of this.

The Super League’s official launch announcement said that the “Founding Clubs” were set to receive €3.5bn to “offset the impact of the COVID pandemic”.

That is consistent with reports of a €200-300m upfront “welcome bonus” to be received by each of the 12 clubs.

It’s pretty clear that some of the clubs involved were counting on that cash to dig them out of their financial holes.

Barcelona and Real Madrid, in particular, have severe debt problems. The Catalan club’s net debt more than doubled to €488m in the year to last June. Madrid’s reported bank borrowed trippled to €150m over those 12 months.

Data compiled by Off The Pitch suggests the collective net debt of the 12 ESL clubs increased by around €840m between 2019 and 2020.

Without that ESL cash injection some might struggle to stay meet their outgoings.

On top of this there is the prospect of penalty payments for the clubs which have now broken their ESL contracts, with legal analysts suggesting such clauses will almost certainly have been inserted by lawyers to bind them in.

Then there is the possibility that national leagues and football administrative authorities could impose their own penalties on the breakaway clubs.

There have also been calls for these clubs to be fined or even relegated, something that would impose yet another severe financial hit on them at the worst possible time.

Wanja Greuel, a European Club Association board member, has said that the clubs involved should be excluded from this year’s Uefa Champions’ League, the lucrative competition the ESL was designed to replace.

It’s not impossible that some of the more indebted clubs could be put up for sale as result - or at least appeal for outsider investors.

Some owners might decide to sell for a different reason.

The attraction of a US-style closed league for elite European clubs to the American bosses of Manchester United, Arsenal and Liverpool was a combination of higher broadcasting revenues, the guarantee of revenue through the elimination of relegation jeopardy and finally the new spending control “framework” that would accompany the ESL and reduce their costs.

It is this combination of high and stable profits which has pushed up the value of the US sports franchises they also own.

If the likes of the Glazer family at Manchester United or John Henry at Liverpool or Stan Kroenke at Arsenal come to the conclusion that a lucrative US-style closed league for Europe is now off the table for the foreseeable future they may also decide to cash in.

However, the most likely buyers of these globally famous clubs would be more rich overseas oligarchs like Sheikh Mansour of Manchester City or Roman Abramovich of Chelsea. Saudi interests last year attempted to buy Newcastle United and the country’s de facto ruler, Crown Prince Mohamed bin Salman, reportedly complained to Boris Johnson when this was blocked by Premier League.

Such owners might not be focused on squeezing profits from clubs, but would they have the real long-term interests of fans and communities at heart?

The fact that Chelsea and Manchester City joined the ESL coup seems to have come as a wake-up call to some fans of these clubs who were previously prepared to overlook such worries as long as these owners were spending big money on players and buying success on the pitch.

This is the reason the UK government earlier this week broached the idea of giving fan groups a golden voting share in clubs or a minimum of 51 per cent ownership, mirroring the system that prevails in the German Bundesliga. It’s been widely noted that this fan veto successful prevented the top German clubs, including last year’s Champions’ League winners Bayern Munich, from committing to join the ESL breakaway group.

The imposition of such as structure on UK clubs would have profound consequences not only on the finances of the game (German matches have lower ticket prices) but also its governance.

In Germany there is league regulation of clubs’ debts, rules which encourage the development of home-grown playing talent and a more equal distribution of broadcast revenues.

(However, it’s important to recognise that Bayern Munich remains utterly financially and competitively dominant in Germany football, despite these controls. Also, supporter ownership structures at Real Madrid and Barcelona in Spain has not resulted in any financial solidarity with smaller Spanish clubs.)

Nevertheless, a potential long-term financial legacy from the ESL fiasco could, ironically, be the kind of spending controls that the clubs involved were mooting for their own cartel.

A very large share of the explosion of broadcasting revenues into elite football clubs over the past three decades has flowed out of their gates as inflated player wages and commissions to rapacious agents. In England, Spain, France and Italy players’ wages account for between 60 and 75 per cent of total revenues.

Indeed, the consultancy firm Vysyble calculates that despite the vast increases in revenues over the past decade, the top English clubs have failed to make any genuine profits over that period, after accounting for the equity injected by owners, but rather £2.7bn of losses.

Uefa’s Financial Fair Play rules were designed to curb this kind of behaviour by preventing clubs from using the external wealth of billionaire owners, or soft debts racked up by major clubs, rather than their own revenues generated by football activities, to compete for players in the transfer market.

But the rules were never particularly tough and, moreover, have sometimes been simply disregarded by the big clubs with oligarch owners, forcing all the top clubs to spend ever greater sums on players and undermining their financial stability in the process.

A possible outcome scenario of the ESL debacle is that the richest clubs will finally realise that such financial controls are in their own interests. It might also embolden national and international footballing authorities to toughen them up and enforce them properly.

The immediate impact of the collapse of the ESL is likely to be financially painful for the rebel clubs.

Yet, in the longer term, a bolstering of financial fair play rules, a stronger voice for fans, improved regulation and the bringing of the top clubs – and their owners - to heel, could make for a more sustainable economic framework for the entire game.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks