Has the criminal justice system finally hit rock bottom?

Analysis: Knife crime reached a record high in 2019 as prosecutions hit a record low – but coronavirus could be a turning point, Lizzie Dearden writes

If you are raped in England or Wales and report it to the police, there is little over a one in 70 chance that the attacker will be prosecuted.

If you become a victim of theft, the figure is one in 20, and one in 14 if you are robbed or physically attacked.

Overall, just 7.1 per cent of recorded crimes resulted in a charge or summons in 2019 – a record low.

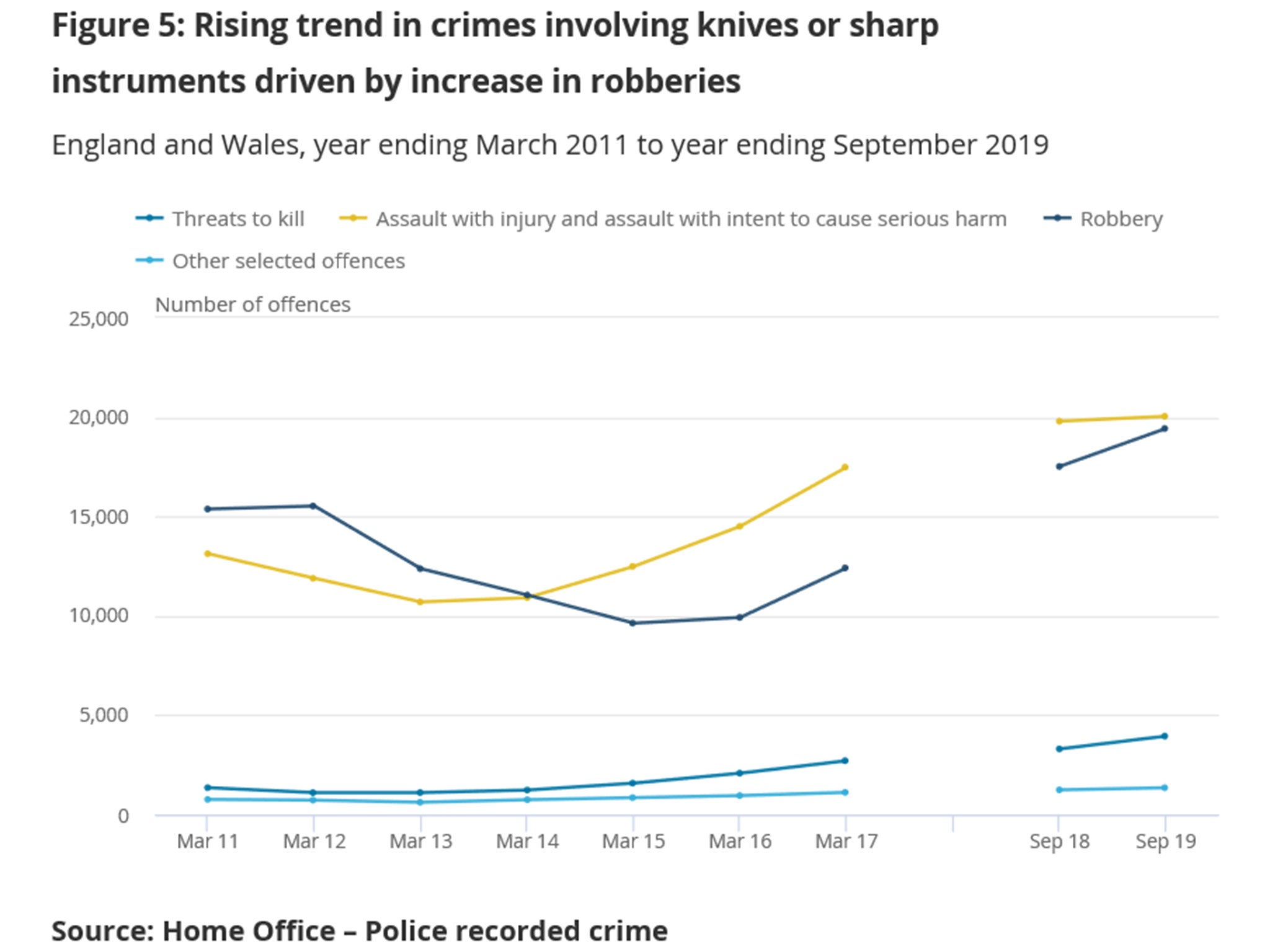

As the grim statistics were published, separate figures showed knife crime hitting a record high.

For years, the numbers have been sliding in opposite directions, with serious crime going up as prosecutions fell.

The Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) has largely blamed police for referring fewer cases for its consideration.

However, officers have accused the authority of “raising the bar” for charging, and demanding more and more evidence from digital devices that often take months to examine.

In January, the government announced that a royal commission on the criminal justice system would deliver a “fundamental review of key issues” and “make it more efficient and effective”.

But for those working inside it, the key issue is clear: austerity.

The justice system bore the brunt of some of the deepest cuts from 2010 onwards, with police forces alone losing 20,000 officers, and almost as many staff.

While Boris Johnson has pledged – unrealistically – to reverse that drop in three years, the CPS remains hundreds of prosecutors short.

Furthermore, the cuts to youth services, mental-health care, social work and other preventative factors have been blamed for worsening the root causes of crime.

Research by the Home Office itself found that budget cuts had contributed to a rise in murders.

Meanwhile, at the other end of the process, reductions in the number of court sitting days to save money have resulted in a backlog of more than 37,000 cases.

The dire situation may finally be at a turning point, however.

Not because of the new government’s funding increases, which still fall short of what was lost, or the many promised reviews and inquiries, but because of the coronavirus.

While the outbreak has injected unwanted chaos into the criminal justice system, forcing the closure of half the country’s courts and seeing trials delayed indefinitely, it has also sparked a dramatic fall in crime.

Offences recorded by police in England and Wales plummeted by 28 per cent in England and Wales in the four weeks to 13 April, compared with the same period in 2019.

And the UK was only in lockdown for three of those weeks, meaning that future reductions could be even sharper.

Provisional data showed a 37 per cent fall in reported rape, a 27 per cent drop in serious assaults and personal robbery, residential burglary down 37 per cent, and shoplifting halved.

While some crime types, including domestic abuse and child abuse, are expected to increase during the lockdown, the number of cases being investigated by police will be dramatically lower.

That fall should slow the number of cases being passed to the CPS and on to the courts, which will take a significant amount of time to clear the existing backlog.

Lockdown is keeping a lid on crime in Britain, and providing unexpected respite for parts of the justice system.

But time will tell whether it marks a turning point, or is merely the calm before the storm.