Spending review: Ignore the big sums – there are painful trade-offs to come

The spending ‘envelope’ may have been set but the details of Wednesday’s comprehensive spending review will leave the chancellor with some tough choices, writes Phil Thornton

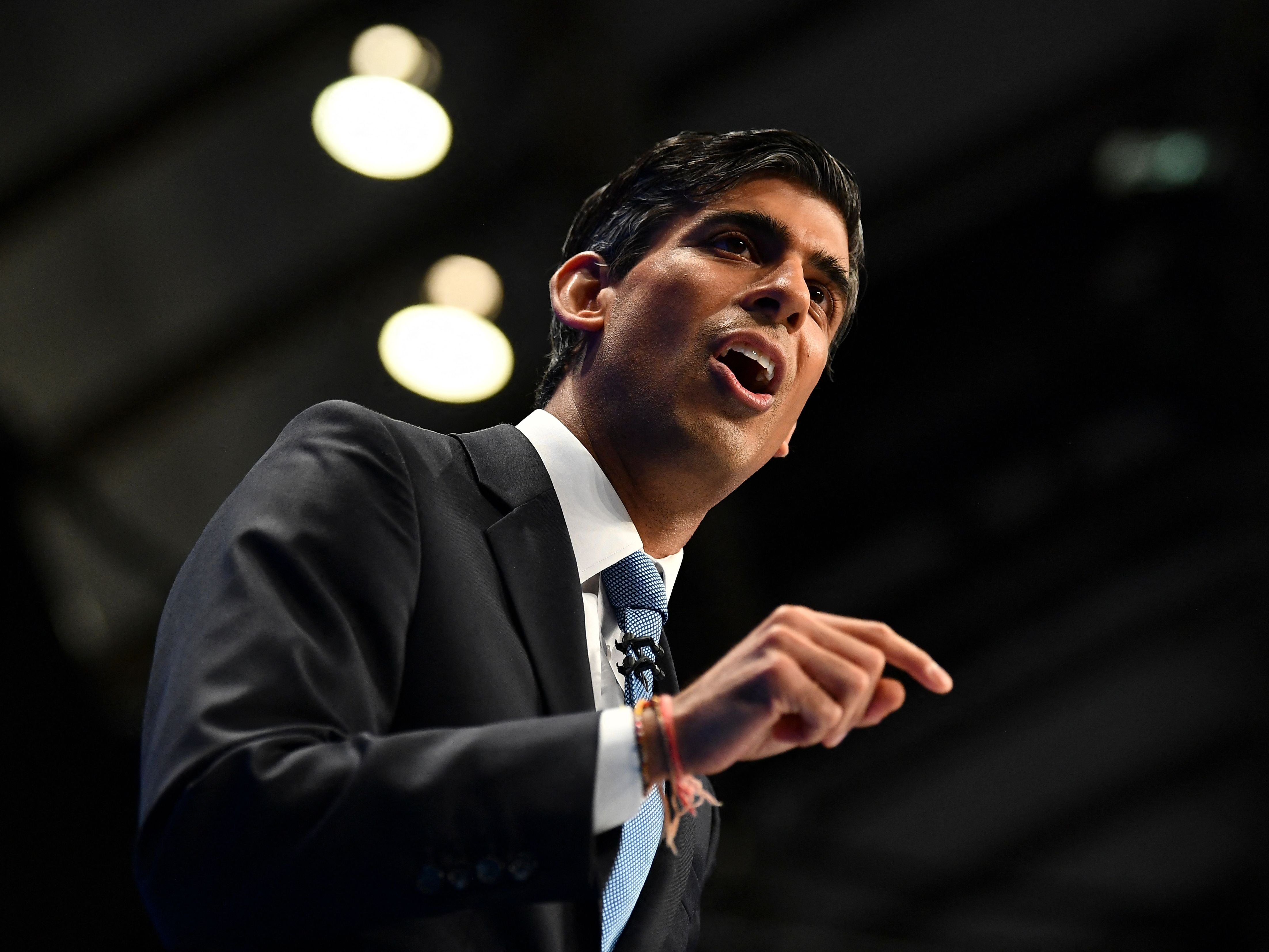

The Budget may get all the headlines this week, but the comprehensive spending review (CSR) to be unveiled by the chancellor, Rishi Sunak, on Wednesday will give the most concrete signal of the government’s intentions for the rest of this parliament up to and beyond polling day.

Forget the slogans of “build back better” and “levelling up”, it is the overall spending remits for departments for the three financial years to April 2025 that will indicate which areas will be prioritised.

The problem for the chancellor is that he has a tricky balancing act to perform, both between the needs of different departments and the need to deliver on the promises of the last manifesto and his desire to offer tax cuts in the next one.

The government has already revealed a large chunk of the spending. Thanks to the 7 September announcement we know that spending will rise by £14bn a year, funded by a corresponding revenue hike thanks to the levy of 1.25 per cent on national insurance contributions by both employees and employers.

This means that core department spending will rise by 3.2 per cent on average a year in real terms. This is an improvement on the 2.1 per cent average annual increase laid out in the Budget, but a cut relative to March 2020.

Of that, the lion’s share will go to the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC): an additional £11.2bn in 2022-23, the first year of the CSR; £9bn in 2023−-24; and £10.1bn in 2024-25. That’s a total of £30.3bn over the three years.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies calculates that, as a result, the DHSC is set for real-terms growth – above the impact of inflation – of more than 12 per cent in that first year.

However, the bulk of this will go towards the NHS. A total of £5.4bn will go towards adult social care services between 2022-23 and 2024-25, or £1.8bn a year to support the social care workforce.

The concern here relates to the fact that the CSR will not offset the annual cuts to spending between March 2020 and March 2021, despite the extra pressures the service has been under.

Furthermore, the pressures related to Covid-19 are unlikely to dissipate at the end of the financial year – especially given the rising trend in deaths and new infections. Sunday night’s announcement of £6bn of extra NHS cash is a good example.

And, of course, health and social care services are not the other ones that may be impacted by higher Covid costs. Education, local government, justice and transport may need extra funding to pay for backlogs that have built up. This will come on top of higher costs from Brexit, demographic trends and a decade of austerity.

The IFS gives two examples – support for public transport operators and a catch-up package for schools – that could each easily require £3bn of extra spending a year. Against that backdrop, it points out that these unprotected departments are facing a real-terms cut of 2.5 per cent, or more than £2bn, in the 2022-23 fiscal year.

Meanwhile, making “meaningful” progress in areas such as social care reform, levelling up and the net zero transition could require tens of billions of extra spending each year.

The plans may also be undermined by rising inflation and hikes in interest rates that increasingly seems to be on the cards. Sunak himself says a 1 percentage point rise in both inflation and interest rates could cost the exchequer £25bn a year.

Higher market interest rates will push up the cost of borrowing for short-term bonds such as one- and two-year gilts as well as for any government bonds that mature and need to be rolled over.

While inflation will reduce the real-terms burden of paying the interest on debt that is not linked to inflation, for index-linked debt the payments will rise as inflation does.

Inflation has a direct impact because a sizeable share of government debt (currently just under a quarter) is index-linked, meaning coupon payments (and the stock of debt) rise automatically with RPI inflation.

All these pressures could combine to make life tricky for Chancellor Sunak, especially over the later years of the CSR leading up to an election. With the levelling-up agenda and the reform of social care to be delivered, the coming years are likely to see some painful trade-offs.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments