Only time will tell if Johnson’s ‘summer of weight loss’ agenda works

With plans to restrict junk food advertising and possibly in-store promotions, what reason is there to think these kinds of measures actually work in reducing obesity? Ben Chu looks at the evidence

The prime minister is preparing to launch an anti-obesity drive to help get the UK population in better shape for a potential second wave of coronavirus in the winter.

On a visit to a GP surgery in east London on Friday, Boris Johnson said: “Obesity is one of the real co-morbidity factors. Losing weight, frankly, is one of the ways you can reduce your own risk from coronavirus.”

The government is hinting that among the measures could be a ban on junk food advertising before 9pm and restrictions on in-store promotions. This follows a “sugar tax” on fizzy drinks devised when David Cameron was prime minister in 2016.

There were some indications that this might be scrapped by the new regime in Downing Street – but now it appears it will stay.

But what evidence is there that these kinds of measures actually work in reducing obesity? And how fair is to hit people – many of whom might be on low incomes – with new taxes like this in the belief that it will make them healthier?

What’s the problem?

Multiple studies of the victims of coronavirus around the world have shown that obesity, alongside age, is indeed a factor that seems to significantly raise an individual’s risk of developing a critical illness and dying from the disease – although the precise biological mechanism behind this heightened vulnerability is uncertain.

It’s also clear that obesity has risen in the UK in recent decades.

The share of the adult population in England with obesity – defined as a Body Mass Index of 30 or higher – has increased from 15 per cent in 1993 to 29 per cent today.

As for children, it’s estimated that around 10 per cent of 4-5-year-olds are obese, rising to 20 per cent of 10-11-year-olds.

The rising rate of obesity is something doctors have been warning about for many years – long before this pandemic – as a source of ill health and premature death.

Many have noted that it is also imposing increasing costs on the health services, with NHS England estimating that treating obesity and its consequences alone currently costs around £5bn every year.

Has the sugar tax helped?

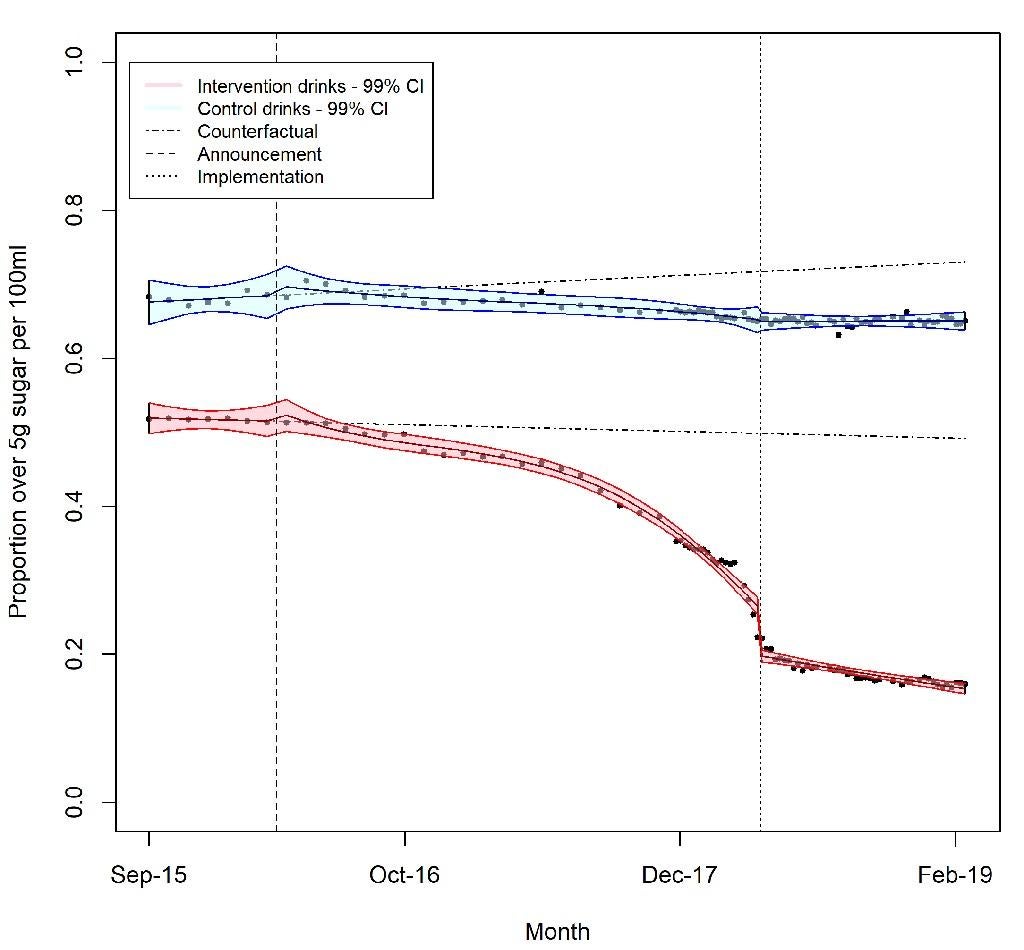

David Cameron’s Soft Drinks Industry Levy (SDIL) was devised in 2016 but was not implemented until April 2018.

It is an 18p charge on drinks containing 5-8g of sugar per 100ml and 24p on those with 8g and more and is directly payable by manufacturers.

The aim of the tax is to reduce sugar consumption by persuading companies to reformulate their high sugar brands in order to avoid paying the levy.

The levy was initially projected to raise £500m a year, but has actually been bringing in around half of that, something cited by ministers as an encouraging sign that manufacturers are lowering the sugar content of their drinks by more than expected.

One study released in February this year backs that up, concluding that the levy has been associated with a reduction in the amount of sugar in soft drinks, although not a reduction in the size of the overall market for soft drinks.

After the sugar tax was introduced the number of high sugar drinks fell

The UK is not the only country that has imposed taxes on fizzy drinks. There have been similar moves in Chile, Mexico, France and some US states. A review of empirical studies last year found that most showed such taxes resulted in reductions in the number of purchases of taxed drinks.

The UK government put out a green paper in July 2019 which suggested the levy could be extended to milkshakes, although it’s unclear whether the government intends to proceed with this.

Don’t these measures hurt those on low incomes?

The consumption of sugary drinks and unhealthy foods is higher among lower-income groups. But so is obesity. In the most deprived areas in England prevalence of excess weight is substantially higher than in the least deprived areas

Among 10-11-year-old children in England from the most deprived decile obesity rates are 24 per cent compared to 12 per cent among those from the least deprived decile.

Some research has found that the costs of soft drink taxes might disproportionately fall on low-income households but that poorer people also lower their sugar consumption by more than others in response.

In other words, they might pay more but also get the largest health gains. And to this gain, we can add a lower risk of dying prematurely from a second wave of coronavirus.

Whether one regards such taxes as fair, in light of the above, will likely depend on how libertarian one’s political and social outlook is.

What about bans on junk food advertising?

The evidence base is smaller in this area than it is for sugar taxes. But researchers from the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) looked into the potato crisps advertising market in 2017.

They managed to match up the TV viewing habits of a large sample of people, the adverts they were exposed to and their subsequent junk food spending decisions. Their conclusion was that a ban on crisp advertising would actually work in reducing demand, cutting crisp sales by around 10 to 15 per cent.

Judging the impact of advertising bans is also more complicated because much depends on what function the advertising is serving.

If it is making the market for products bigger than it otherwise would be any curbs on junk food advertising would be expected to yield health gains. But if it is merely providing information to consumers about the merits of different products the health gains might be low or even non-existent. It’s very hard to discern the difference, not least because advertisers themselves do not always know.

Another possibility when it comes to banning or restricting television junk food advertising is that it may simply shift elsewhere, not least online, which again may mean the overall health benefits are not large.

One study found that after Ofcom banned junk food advertising during children’s TV programming in 2007 the actual exposure of children to unhealthy food advertising remained the same despite broadcasters adhering to the ban.

Researchers said this was because children watch more television than just children’s programmes.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

10Comments