Biden’s gamble shows soft power is key to Boris Johnson’s ‘levelling up’ plan

The decision by US Democrats to tie a bill mandating $1 trillion of spending on traditional infrastructure to a measure to unlock three times that investment in people is a lesson for the UK on how to boost 21st century economic growth, says Phil Thornton

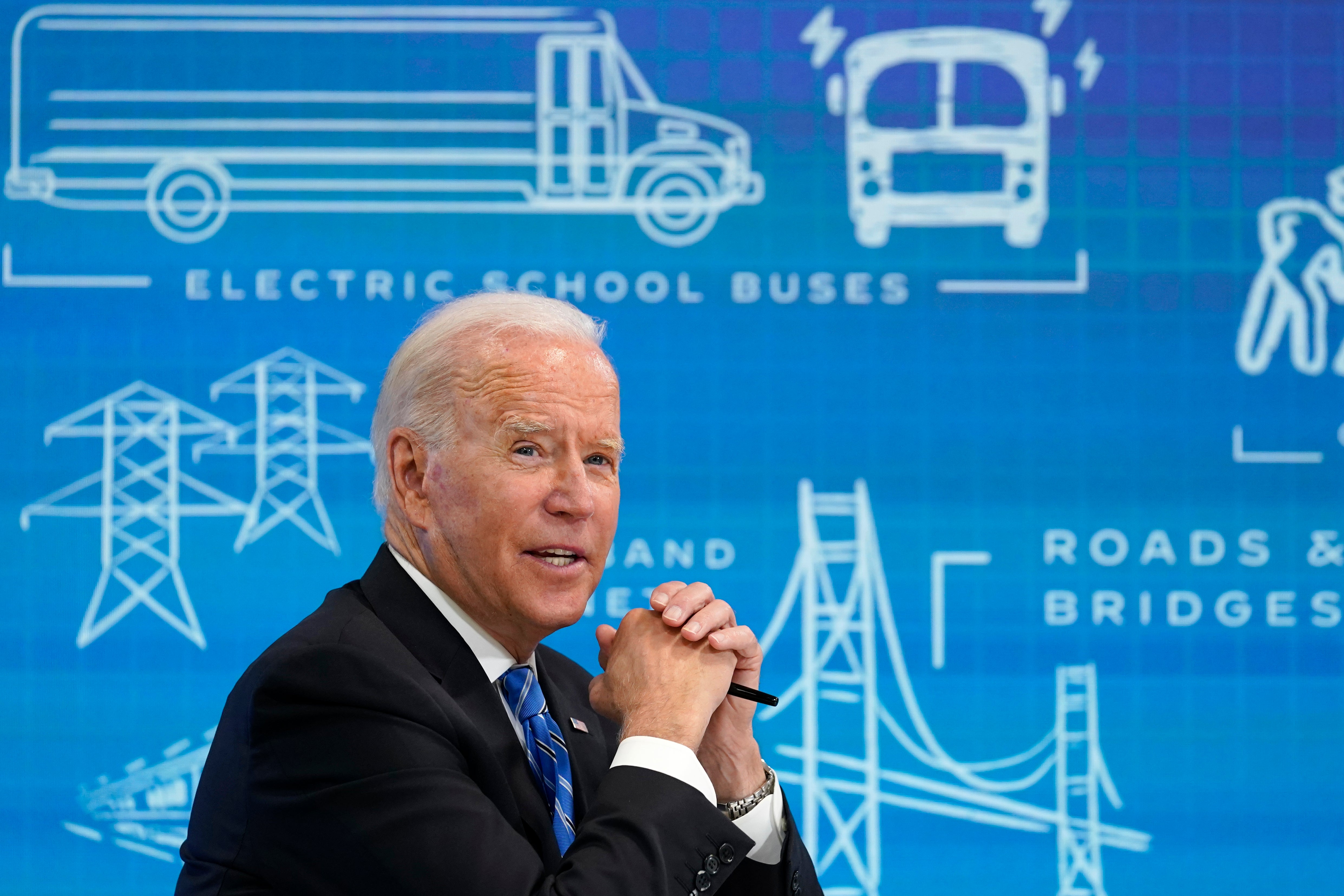

The passage of US president Joe Biden’s $1 trillion (£720bn) infrastructure bill through the bitterly-divided Senate is a rare gleam of sunlight for a global economy ravaged by Covid-19, the climate emergency and extreme political partisanship.

The upbeat feeling is not just because of what is in the bill – although that is important. It is significant because the Democrats have insisted its passage through the House of Representatives will be tied to a much larger measure to mandate $3.5 trillion (£2.53 trillion) of expenditure on so-called “soft” infrastructure.

As we have seen closer to home, politicians tend to focus on a certain type of infrastructure project, such as the multi-billion pound HS2 rail project linking London to the north because of politicians’ ability to look tough by turning up in high-vis jackets and hard hats.

But these projects often run over budget – HS2 is now rumoured to cost £107.7bn compared with the original bill of £32.7bn and sometimes fail to deliver the promised benefits while causing huge disruption and environmental damage. And that is without discussing the cancelled Garden Bridge or the fairytale Scotland-Northern Ireland tunnel.

Of course, when delivered efficiently, hard infrastructure is an essential ingredient for long-term growth. The US plan contains proposals to inject funding into improving the nation’s roads, bridges, pipes, ports and internet connections.

While the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act will get an easy passage through the House of Representatives thanks to the Democrats’ eight-seat majority, the real focus will be on the $3.5 trillion budget bill that contains social programmes and climate measures.

This all-encompassing legislation will bring the country’s approach to infrastructure into the 21st century by including investment in human capital. In plain English this means universal pre-kindergarten for three- and four-year-olds, cutting taxes for families with children, and investing in public universities.

It expands the 2010 Affordable Care Act, invests in home and community-based health care, and reduces the cost of prescription drugs. It also invests significantly in measures to combat climate change.

In the UK, spending on this soft infrastructure has hitherto been a poor relation despite the obvious benefit to the economy of people-focused activities. Tourism is currently worth £100bn a year to the UK economy, for example.

As Professor Ian Wray of Liverpool University has pointed out, people do not visit Britain for the weather. “It is widely accepted that Britain’s soft power assets and its strongest and most competitive economic sectors are in services, such as education, creativity, tourism, music, literature, fine art and the media generally,” he said in a submission to a UK2070 Commission inquiry.

“For services like these, access to concerts, conferences and theatres is more important than access to motorways.”

Soft infrastructure, both cultural and environmental, also helps to attract and retain talented people, who are the bedrock of 21st century economy.

The UK government will have an opportunity to put this thinking into practice in late October when chancellor Rishi Sunak sets out his spending plans for the remainder of this parliament.

There is strong speculation that he will want to keep a cap on spending to restore order to the public finances and the Tories’ reputation for fiscal responsibility.

But newly-elected MPs in Labour’s former Red Wall seats in the north of England know their continued electability depends on the government putting money into schemes that visibly change constituents’ lives.

Last November Bury South MP Christian Wakeford said that, for him, levelling up was not about investing in concrete, new roads and rail links. “For me, it is about education, skills and those communities that we represent,” he told the Commons. “When we focus on our infrastructure for the North, it truly has to be a soft infrastructure-led, community-led and community-driven process that we are all part of.”

At the heart of communities are schools and last week’s A-level results highlighted the need for continued focus on education. There were wide disparities in regional results with almost half (47 per cent) of pupils in London and the southeast receiving an A* or A grade compared with 39 per cent of those in the northeast of England.

As Sir Kevan Collins, the government’s education recovery commissioner who resigned in June over a lack of funding for his proposals, told the BBC, money put into education was not “spending” but investment in the future. “Improving education and reducing inequality in education has got to be a fundamental part of playing in the levelling up agenda,” he said.

It is a long way from the Washington Beltway to ministerial negotiations in the Cabinet Office in Whitehall, but the clear message coming over the Atlantic is that governments must invest in people as the best guarantor of future prosperity.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks