As crazy as it sounds, the Bank of England is looking on the bright side for the UK economy

Analysis: It’s actually welcome to see that policymakers are not assuming that the British economy is beaten, says Ben Chu

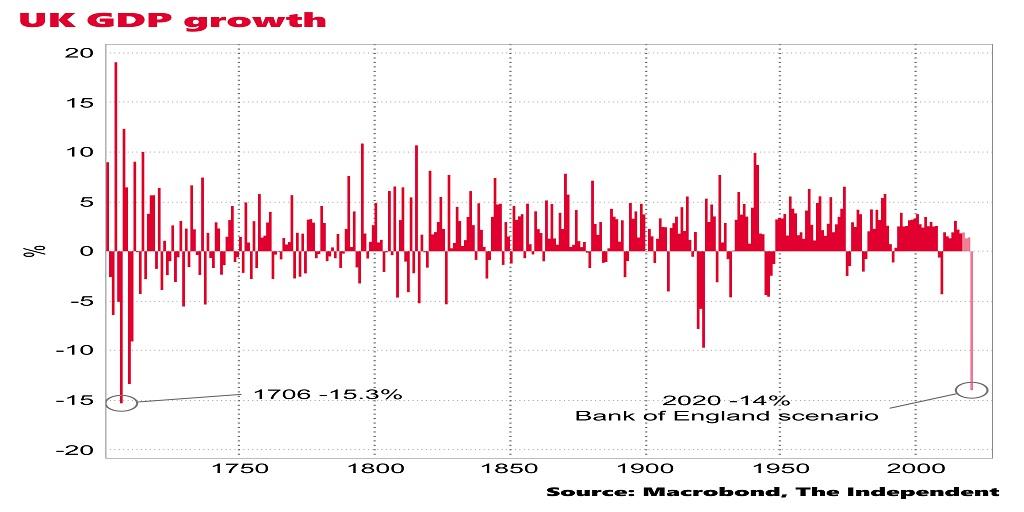

The headlines from the Bank of England’s latest set of projections for the economy are awful on a historic scale.

A 25 per cent decline in GDP in the second quarter of the year would be the worst seen in at least 100 years.

And the 14 per cent decline in the bank’s “plausible illustrative economic scenario” for the full year would be the worst since 1706, when Scotland and England were formally joined in union.

It would be time to rewrite the economic history books.

And yet, like their counterparts at the Office for Budget Responsibility last month, the economists of the central bank are not succumbing to pessimism.

What matters more than anything for the households and businesses that comprise an economy is the long-term potential rate of economic growth, not fluctuations in activity from year to year – even when those fluctuations are as sickeningly wild as this. As long as economic growth steadily rises, incomes and profits should follow over the medium to long term.

And the view of the bank is that our underlying national economic potential shouldn’t be harmed much at all by this lockdown.

“We expect that there will be some longer-term damage to the capacity of the economy, but in the scenario we judge these effects to be relatively small,” said Andrew Bailey, the bank’s governor.

Worst year for the economy since 1706

The question of course is: are the predictions right?

There are lots of reasons, which the bank itself acknowledges in its Monetary Policy Report, why they might not be. Companies, traumatised by this near-death experience, might not invest or hire, which will harm our potential productivity growth.

Plus, in the post-Covid-19 world, lots of industrial equipment might turn out to be in the wrong place. Or companies may reshore their operations, eroding their efficiency.

Loss-making banks may not lend to companies, even those with decent growth potential. Some firms might never come into existence.

Workers who lose their jobs may find their skills wasting away, making them less productive on a personal level. “Scarring” is the word.

The last recession yielded a decade-long productivity disaster for the UK. Indeed, it was still dragging on as we crashed into this pandemic. It would take some with Micawber levels of optimism to be convinced something similar won’t happen again when we come out of it.

Yet perhaps the bank is right to assume the best. One of the likely reasons that productivity growth was so abysmal after the last recession was that broken banks starved the real economy of lending. Cuts in infrastructure and other forms of public investment by the government as part of its austerity programme also contributed.

A soft line on bank restructuring and fiscal austerity were not inevitable – they were policy mistakes. As we look to emerge from this crisis it’s actually welcome to see that policymakers are not assuming that the UK economy is beaten, that productivity growth is all but over.

That makes it more likely that they will put fiscal and monetary policy on stimulatory settings, rather than pessimistically settle for less.

Hoping for the best doesn’t mean it will happen, but it can help avoid mistakes. Low economic expectations are liable to be a self-fulfilling prophesy.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments