Mites mating on our faces at night so dependent on humans ‘they face evolutionary dead end’

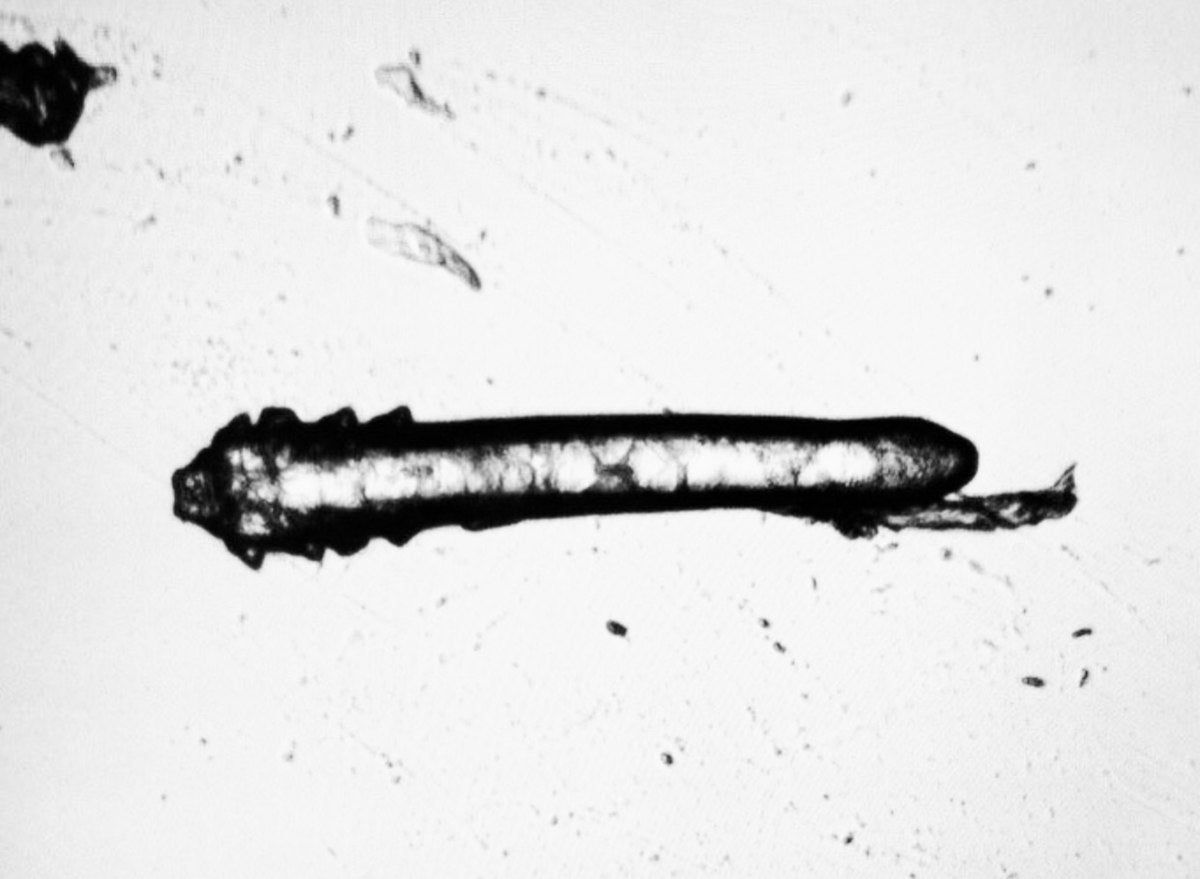

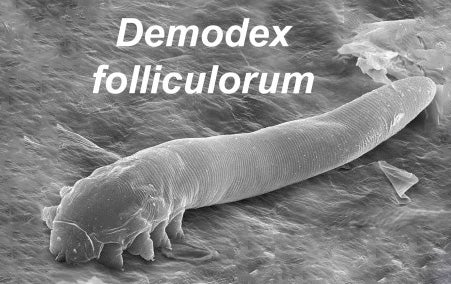

The tiny organisms found in human hair follicles measure at 0.3mm long

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Microscopic mites that live and mate in our skin at night may soon become ‘one with humans’, new research claims.

Due to their isolated existence and consequential inbreeding, they are losing unnecessary genes and are transitioning from external parasites to internal symbionts.

Passed on during birth, the mites measure around 0.3mm long and are found in the hair follicles on the face and nipples, including eyelashes.

The mites are active at night and move between follicles to mate. They eat sebum which is naturally released by cells in the pores.

Dr Alejandra Perotti, Associate Professor in Invertebrate Biology at the University of Reading, co-led the research of the first ever genome sequencing study of the D,folliculorum mite.

He said: “We found these mites have a different arrangement of body part genes to other similar species due to them adapting to a sheltered life inside pores. These changes to their DNA have resulted in some unusual body features and behaviours.”

The in-depth study of the DNA revealed that because of their isolated existence with no exposure to external threats, no competition to infest hosts and no encounters with other mites with different genes, genetic reduction has caused them to become extremely simple organisms with tiny legs powered by just 3 single cell muscles.

They survive with the minimum repertoire of proteins – the lowest number ever seen in this and related species.

Gene reduction is the reason for their nocturnal behaviour: the mites lack UV protection and have lost the gene that causes animals to be wake up at daylight.

They are also unable to produce melatonin – a compound that makes small invertebrates active at night – however, they fuel their all-night mating sessions using the melatonin secreted by human skin at dusk.

Their unique gene arrangement also results in the mites’ unusual mating habits. Their reproductive organs have moved anteriorly, and males have a penis that protrudes upwards from the front of their body meaning they have to position themselves underneath the female when mating, and copulate as they both cling onto the human hair.

One of their genes has inverted, giving them a particular arrangement of mouth-appendages extra protruding for gathering food. This aids their survival at young age.

The mites have many more cells at a young age compared to their adult stage. This counters the previous assumption that parasitic animals reduce their cell numbers early in development. The researchers argue this is the first step towards the mites becoming symbionts.

The lack of exposure to potential mates that could add new genes to their offspring may have set the mites on course for an evolutionary dead end, and potential extinction. This has been observed in bacteria living inside cells before, but never in an animal.

Some researchers had assumed the mites do not have an anus and therefore must accumulate all their faeces through their lifetimes before releasing it when they die, causing skin inflammation. The new study, however, confirmed they do have anuses and so have been unfairly blamed for many skin conditions.

Dr Henk Braig, co-lead author from Bangor University and the National University of San Juan, said: “Mites have been blamed for a lot of things. The long association with humans might suggest that they also could have simple but important beneficial roles, for example, in keeping the pores in our face unplugged.”

The research was led by Bangor University and the University of Reading, in collaboration with the University of Valencia, University of Vienna and National University of San Juan. It is published in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments