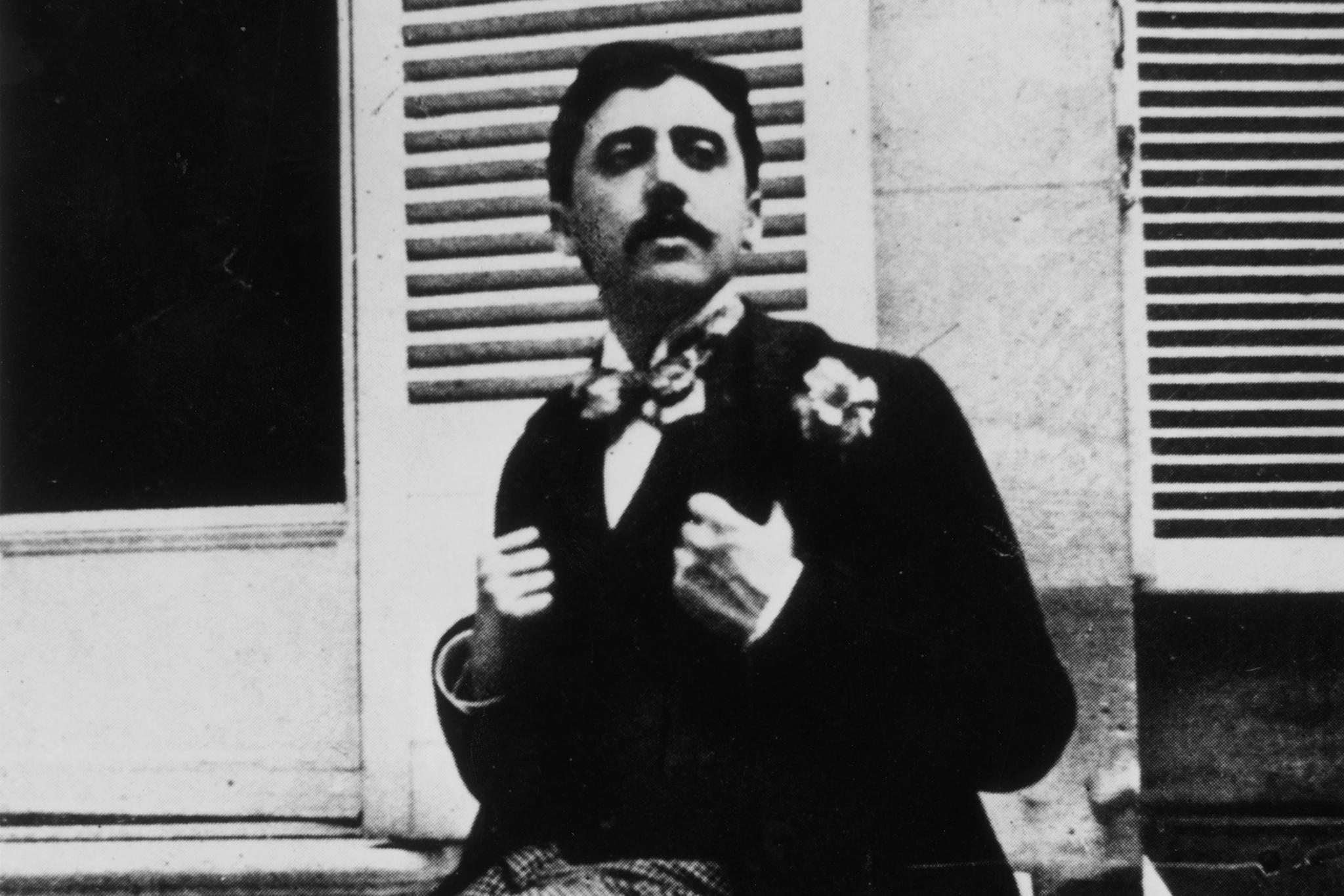

Book of a lifetime: A la Recherche du Temps Perdu (In Search of Lost Time) by Marcel Proust

From The Independent archive: Michael Arditti tackles Proust’s mammoth meditation on time, longing and regret

Marcel Proust’s A la Recherche du Temps Perdu holds the record for the book most likely to be found alongside the Bible and Shakespeare on Radio 4’s celebrity-packed Desert Island. In part this reflects the book’s sheer length, with enforced isolation allowing the castaways to tackle its 3,000 densely packed pages. But it is also a tribute to its widely acknowledged status as the greatest novel of the 20th century; perhaps even of all time.

In his masterpiece, Proust, who was born in 1871 and died in 1922, married the predominant impulse of the 19th-century novel – to portray the workings of society – with the predominant impulse of the 20th – to chart an individual consciousness. So he offers both a panorama of Parisian life at a time of immense upheaval, with the aristocracy ceding power to the newly-rich middle class, and an intimate study of a man as he moves from a privileged childhood to a disillusioned middle age.

There are over a hundred major characters, and every reader will have his or her own favourites. These may be the heart-warming portraits of his mother and grandmother, or of the family maid, Françoise, full of peasant prejudice and dogged devotion. They may be the satiric portraits of the nouveau-riche patrons, the Verdurins, and their pretentious artistic salon; or of the great aristocrats, the Duc and Duchesse de Guermantes.

The former is so preoccupied with social niceties that he is unable to feel any emotion at the news that his old friend, Swann, is dying, while being moved to fury at his wife’s wearing the wrong-coloured shoes. Love in its myriad forms is the central theme of the novel, although the narrator’s passion for Albertine, the young girl whom he meets on holiday in Normandy, is arguably its weakest strand (Proust never satisfactorily transforms his homosexual inspiration into a heterosexual narrative).

Literature contains no more powerful account of erotic obsession, however, than that of the cultivated Charles Swann for the demi-mondaine Odette de Crecy, or of sexual self-abasement than that of the Baron de Charlus’s infatuation with the venal violinist, Morel.

I felt a personal connection to Proust long before I knew the nature of his achievement. My great-uncle lived near the town of Montfort l’Amaury in northern France to which Celeste Albaret, Proust’s former housekeeper, moved in later life. While he would take selected house guests to meet her, he steadfastly refused the requests of his precocious great-nephew, rightly suspecting that I was seeking an adventure rather than a pilgrimage.

Both Celeste and my uncle died before I opened a single page of A La Recherche, but my recollection of that missed opportunity has forever coloured my reading of a work, which is itself so infused with regret for missed opportunities and which is, in every sense, the book of a lifetime.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks