Who owns the sentiment in a love letter?

Love letters often outlive the feelings they contain. After hearing from an old flame, Christine Manby explores what happens when they come back to haunt you

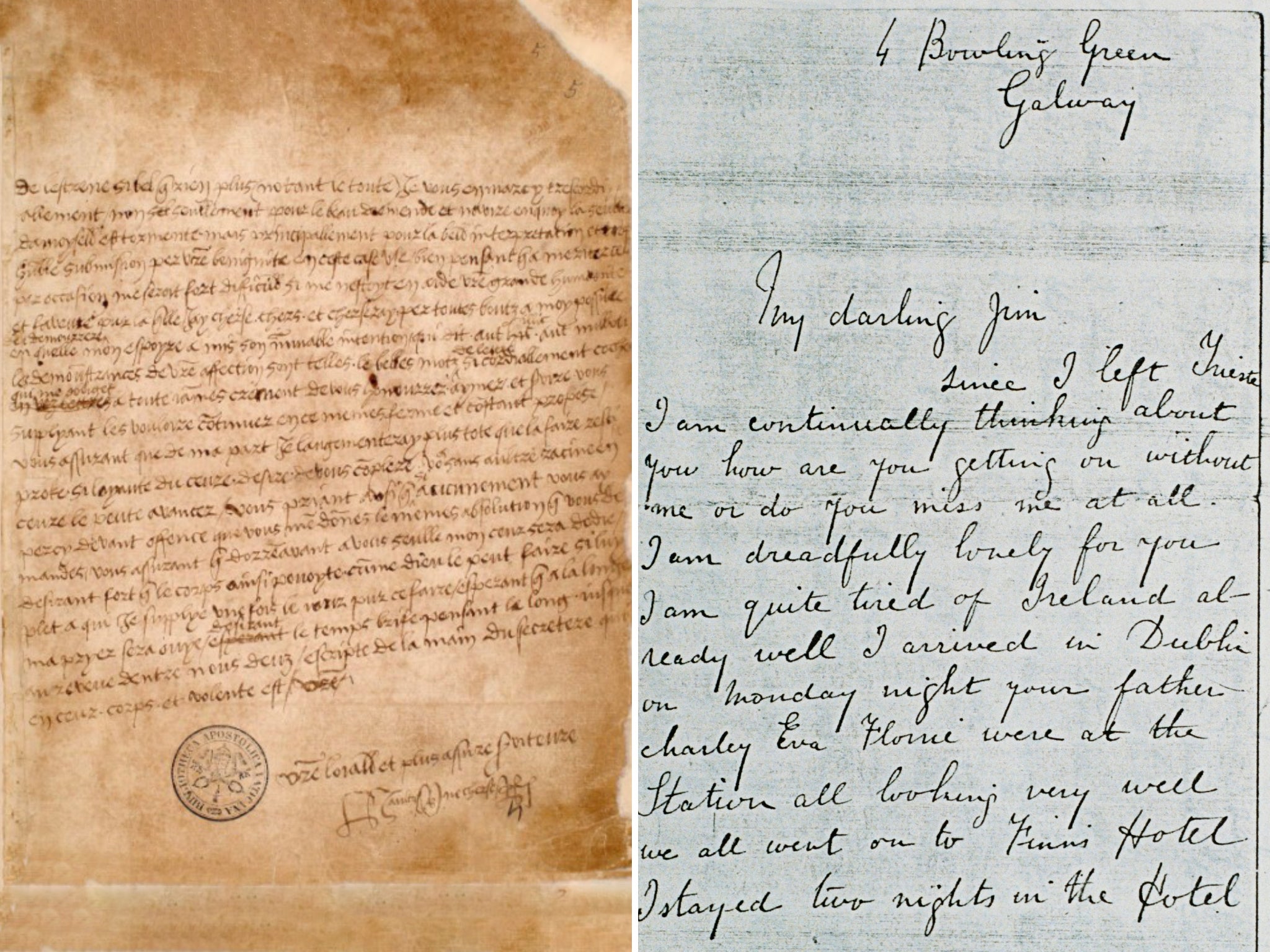

In the summer of 1527, that notorious romantic Henry VIII wrote to young Anne Boleyn: “My mistress and friend, my heart and I surrender ourselves into your hands, beseeching you to hold us commended to your favour…” Henry goes on to describe the pain of their being apart – he was at this time still married to the long-suffering Catherine of Aragon – and encloses his “picture set in a bracelet” so that Anne might not forget him. Well, we all know how that turned out. Poor Anne lost her head and that ancient love letter – along with 17 others in more or less the same vein – is now in the possession of the Vatican Library. Possibly not what Henry imagined when he put quill pen to parchment in the throes of early love.

These days, we’re more likely to send an email than walk to the nearest post box but there’s still something about a handwritten letter that adds a certain solemnity to the feelings expressed therein. So what happens when the letter itself long outlives the sentiments scribbled upon it? Particularly when those sentiments have the potential to embarrass the sender? Or even the receiver?

As the internet increases its grip on our daily lives, we’re all more aware of the dangers of putting our thoughts out into the digital ether. An email, once it lands in the recipient’s in-box, might be forwarded and reproduced many thousands of times with a couple of clicks or have phrases cut and pasted and taken out of context. So, is it any safer to commit thoughts to paper and ink?

In my teens and twenties, I was a prolific letter writer. I was a student in the Nineties before email and mobile phones were ubiquitous and, in lieu of texts and WhatsApp messages, we left handwritten notes pinned to corkboards on each other’s bedroom doors: “College bar at 7.” “Can I borrow your essay on squid?” More personal messages were delivered in sealed envelopes left in the porter’s lodge.

I left university with bags full of these notes. The handwriting of my friends was as dear to me as photographs of their faces. Even the scrap paper they’d written on had meaning, torn as it was from flyers advertising plays and bands we’d seen. Alongside the paper “texts” were dozens of letters from my college boyfriend, which veered between sentimental and angry, with nothing much in between. We were far from a star-crossed match.

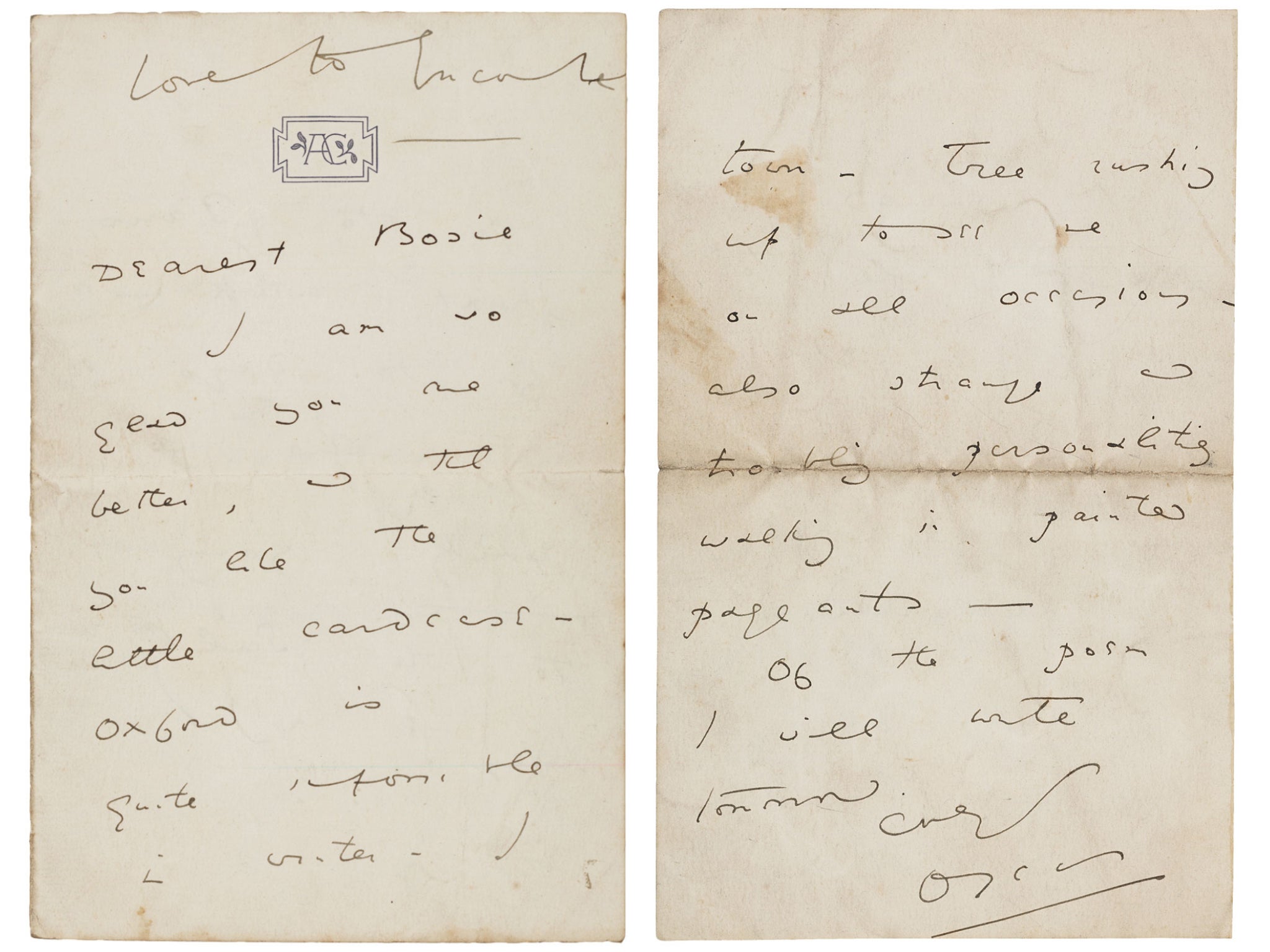

Having met, aged 24, a man I thought I might spend the rest of my life with, I took those old letters to the dump. I felt a sense of relief as I got rid of the physical evidence of my youthful emotional incontinence. I assumed that most people did something similar, because who wants their eventual significant other to stumble upon the purple prose they inspired in others who ended up having no real significance at all? So I was surprised to open the direct messages on my Facebook account to find a message from someone I dated for just a couple of months in 1995 to which he had attached photographs of two letters I’d written to him during our brief relationship.

I’m not sure what emotion my old flame hoped to rekindle in me with those photographs but it was probably not the red-hot embarrassment I felt when I saw my girlish handwriting with its big loopy Gs and Ys. Though I was alone at my desk, I blushed so hard that anyone seeing me staring at the message might have been forgiven for thinking my former amour had sent me a naked snapshot rather than of two pages of my own untidy scrawling.

I couldn’t bear to zoom in and look at the content of those letters. I remembered how the relationship had ended and how upset I’d been at the time. Upset enough to make a fool of myself in black biro on paper pinched from the printer at work. Seeing the letters in digital form also made me feel oddly vulnerable. What if he sent them to someone else too? For a laugh.

‘I think I would know Nora’s fart anywhere, I think I could pick hers out in a roomful of farting women’

Of course, my letters won’t end up in the Vatican Library or plastered on the front pages of a tabloid, but such things have long been a consideration for people in the public eye. And how lucky we’ve been to be able to see some of their private correspondence.

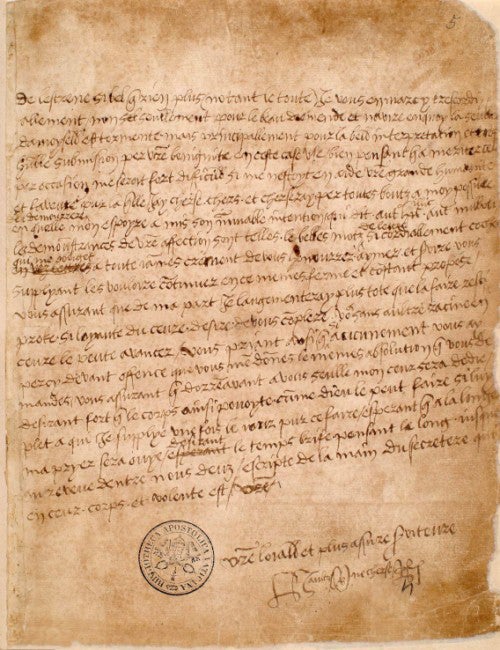

That especially famous man of letters, Oscar Wilde, sent exquisite missives to his lover Lord Alfred “Bosie” Douglas, which was made all the more remarkable by the social mores of the time, which rendered their homosexual love illegal. Some of them were published in Oscar Wilde: A Life In Letters. In January 1893, Wilde wrote to Bosie:

“My Own Boy, Your sonnet is quite lovely, and it is a marvel that those red rose-leaf lips of yours should be made no less for the madness of music and song than for the madness of kissing. Your slim gilt soul walks between passion and poetry. I know Hyacinthus, whom Apollo loved so madly, was you in Greek days.”

I don’t suppose Wilde and Bosie ever dreamed their letters would become public property, but who would mind the world knowing that they had been referred to in such poetic terms? Who would mind it being known that they could write such a wonderful billet doux?

Eleanor Roosevelt, wife of United States President Franklin D Roosevelt, is revered for her political impact and her dedication to improving the lot of America’s underprivileged, but there was much more to her than her role as the longest serving first lady. In 1998, her private correspondence archive was opened to the public. It contained 18 boxes of letters exchanged between Roosevelt and Lorena Hickok, a journalist, whom Roosevelt nicknamed “Hick”.

During her lifetime, Roosevelt’s relationship with Hick attracted speculation but it was generally accepted that the two women were simply friends. However there’s nothing ambiguous about the letters, 300 of which were published in Empty Without You, with annotations by editor Rodger Streitmatter. The letters give a clear picture of Roosevelt’s sexuality and just how much she and Hick meant to one another.

On 5 March 1933, at her husband’s inauguration, Roosevelt wore a sapphire ring given to her by Hick. That same day she wrote: “Hick my dearest – I cannot go to bed tonight without a word to you. I felt a little as though a part of me was leaving tonight. You have grown so much to be a part of my life that it is empty without you.” She wrote another letter the following day: “Hick, darling – Ah, how good it was to hear your voice. It was so inadequate to try and tell you what it meant. Funny was that I couldn’t say je t’aime and je t’adore as I longed to do, but always remember that I am saying it, that I go to sleep thinking of you.”

One imagines that Roosevelt and Hick, who were unable to go public with their real feelings for each other, might have taken in their stride the idea that those feelings would eventually be made public in a more understanding time. I’m not so sure the same might be said about Irish writer Elizabeth Bowen , whose letters to her lover, Humphry House, were published last year in The Shadowy Third. The book includes a letter from 1935, in which Bowen writes about her pain upon hearing that House’s wife Madeline is pregnant again. “You know the whole area is painful when I myself wanted a child so much.” Would Bowen have been so unguarded had she known that some 85 years later, that letter would fall into the hands of her love rival Madeline’s granddaughter, The Shadowy Third’s author, Julia Parry?

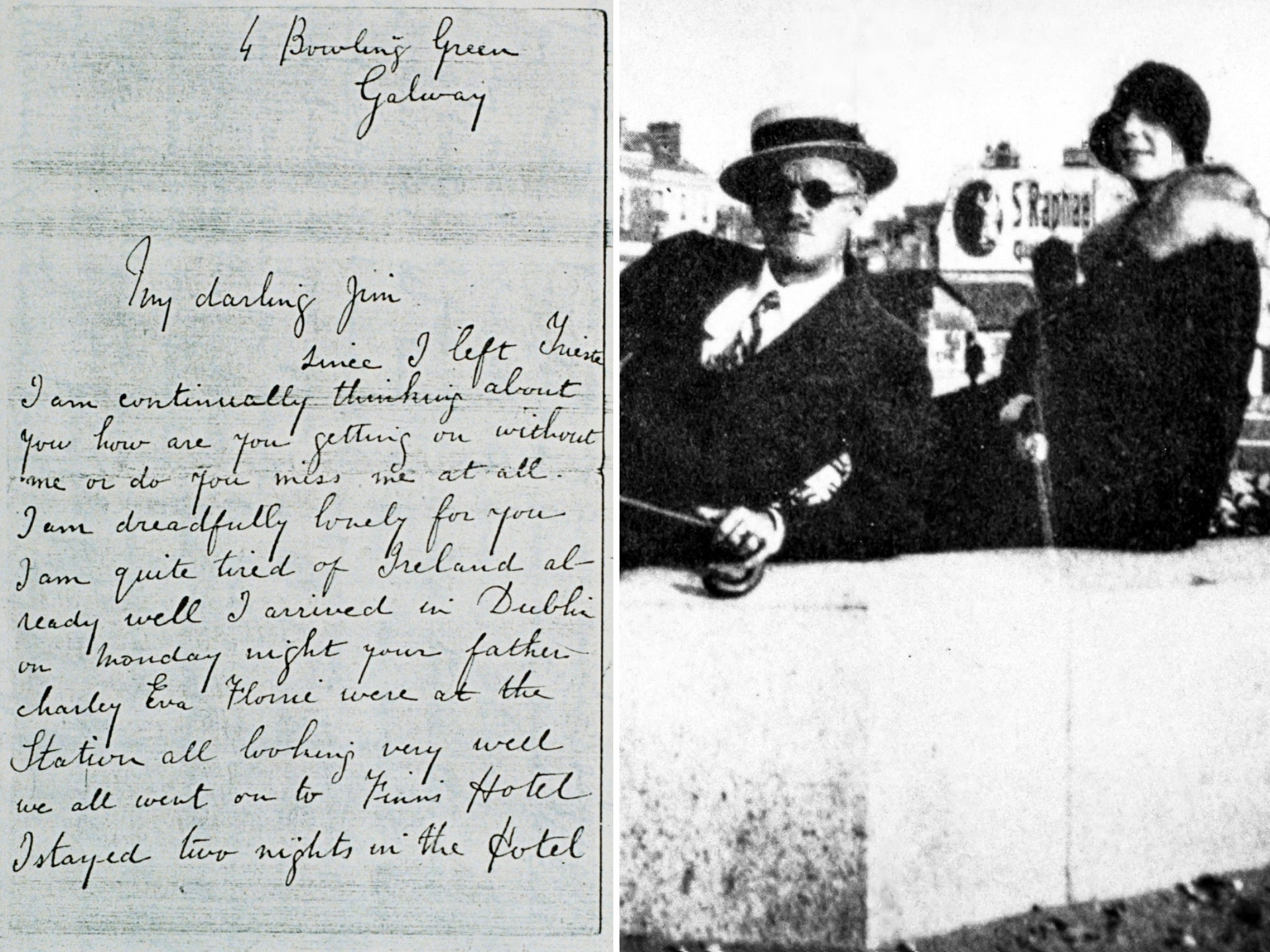

And would James Joyce’s wife Nora Barnacle, have wanted the neighbours to see the contents of his letters to her? The author of Ulysses, was besotted with his wife but his letters to her are often less than elegiac. A typical example begins: “My sweet little whorish Nora, I did as you told me, you dirty little girl, and pulled myself off twice when I read your letter. I am delighted to see that you do like being f***ed arseways.” In another letter, he waxes lyrical about her copious farts. “I think I would know Nora’s fart anywhere,” he writes. “I think I could pick hers out in a roomful of farting women.”

The letters are shockingly, thrillingly vulgar, though, as Joyce acknowledges in another note, he was very different in public. “As you know, dearest, I never use obscene phrases in speaking. You have never heard me, have you, utter an unfit word before others. When men tell in my presence here filthy or lecherous stories I hardly smile. Yet you seem to turn me into a beast.”

Perhaps Eliot’s grief for Vivienne made it impossible for him to finally commit to the woman who had usurped her place in his heart

Who has the right to publish a letter that might change the public perception of its author? The first thing to consider is ownership. The letter itself – the paper, the ink upon it, the lipstick kiss on the back of the envelope – almost always belongs to the recipient and becomes part of their estate upon their demise. But the words therein? That’s a different matter altogether.

In general, copyright in the literary work that is the substance of the letter still belongs to the author. After the author’s death, copyright subsists for another 70 years and is considered property that forms part of the author’s estate. In terms of prospective use of the literary work by anyone other than the author or their heirs it gets a bit tricky. There is sometimes the possibility that a letter might be published under the scope of “fair dealing” for the purposes of criticism or review.

Another defence of copyright infringement might be that publication is in the “public interest”, which was one of the arguments run unsuccessfully by Associated Newspapers Ltd, publishers of the Mail On Sunday and the Mail Online, after they printed a letter from the Duchess of Sussex to her father Thomas Markle. The Duchess won her claim that her privacy had been breached, with Mr Justice Warby saying in his judgement that “the claimant had a reasonable expectation that the contents of the Letter would remain private”.

Perhaps the simplest way to preserve your privacy is to ensure that you remain on good terms with the people you write to and can count on them not sharing your deepest confidences. Roosevelt and Hickok are believed to have destroyed their most private and erotic letters to one another. Other writers, realising that publication of their private correspondence is inevitable, have had to take a different tack.

Princeton University recently displayed for the first time a set of very important literary love letters. Their author was the poet TS Eliot. Their recipient was scholar Emily Hale, the woman believed to have been the inspiration behind some of Eliot’s most highly regarded poems, including “Burnt Norton”, the first poem of Eliot’s Four Quartets. In 1969, Hale bequeathed the letters to Princeton, together with photographs and a short explanation of her relationship with Eliot, with strict instructions that they were to remain under lock and key until 50 years after her death. In January 2020, those 50 years were up.

The letters reveal an intense relationship. Eliot and Hale met for the first time at Harvard in 1912. For Eliot, the attraction was immediate. In 1914 he declared his love to Hale but it went unrequited. Soon afterwards, Eliot moved to England and in 1915, he met and quickly married Vivienne Haigh-Wood, a governess from Cambridge.

Eliot would not see Hale again until 1927 but upon doing so, he admitted that his feelings for her were unchanged. In October 1930, Eliot wrote, “My love is as pure… as any love can be.” But with Eliot married, albeit unhappily, he and Hale could not pursue a relationship. That changed in 1935, when Vivienne was admitted to the psychiatric hospital where she would spend the rest of her life. For the next four years, Eliot and Hale spent their summers together in the Cotswolds and Hale allowed her feelings for the poet to deepen.

In 1947, Vivienne died, leaving Eliot free to marry Hale at last. But he didn’t propose. Perhaps Eliot’s grief for Vivienne made it impossible for him to finally commit to the woman who had usurped her place in his heart. Hale wrote to a friend, saying the “mutual affection he and I have had for each other has come to a strange impasse.” The letters stopped. Ten years later, Eliot married Esme Valerie Fletcher.

In 1960, hearing that Hale intended to leave his letters to Princeton, Eliot wrote to the university pre-emptively, giving some context to the end of their relationship. In the statement which he asked to be made public at the same time as his letters, he explained: “Emily Hale would have killed the poet in me.” He further added that he had come to realise that he had only ever been in love with “the memory” of Hale as the young woman he had fallen for while studying at Harvard. His tempestuous marriage to Vivienne had been the real source of his poetic inspiration.

Eliot’s statement was perhaps also an effort to spare the feelings of his second wife, of whom he wrote: “I cannot believe that there has ever been a woman with whom I could have felt so completely at one as with Valerie.” He ended the statement with a postscript that seems especially stinging. “The letters to me from Emily Hale have been destroyed by a colleague at my request.”

Was Eliot right to have rendered his correspondence with his purported muse one-sided? Eliot scholars must be left feeling they have been robbed of the whole picture of his relationship with Hale and thus of the genesis of his finest works. That half of the correspondence which does remain undoubtedly enriches our understanding of Eliot’s literary output, as do the letters of Wilde and Bowen and fart-obsessed Joyce with regard to their work. However, I for one like Eliot better for his having sent a clear message to Princeton and to Hale that even a writer should be able to expect some of their words to remain entirely private, especially where the feelings have faded faster than ink.

Eliot wanted to be allowed to have moved on. Don’t we all? When eventually I plucked up the courage to zoom in and read the letters I’d written to my old flame, the contents were less cringe-worthy than I imagined. All the same, as a relic of a fleeting affair, they definitely weren’t worth keeping and I very much wished my correspondent hadn’t bothered. His motives in reminding me of those long-forgotten feelings were still unclear.

After a few days, I sent my reply to his note from the blue, asking for news of his family. Then I told him that I wish I’d stamped “Burn After Reading” across the top of those gushing letters from 1995 and left it at that. He hasn’t written back.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks