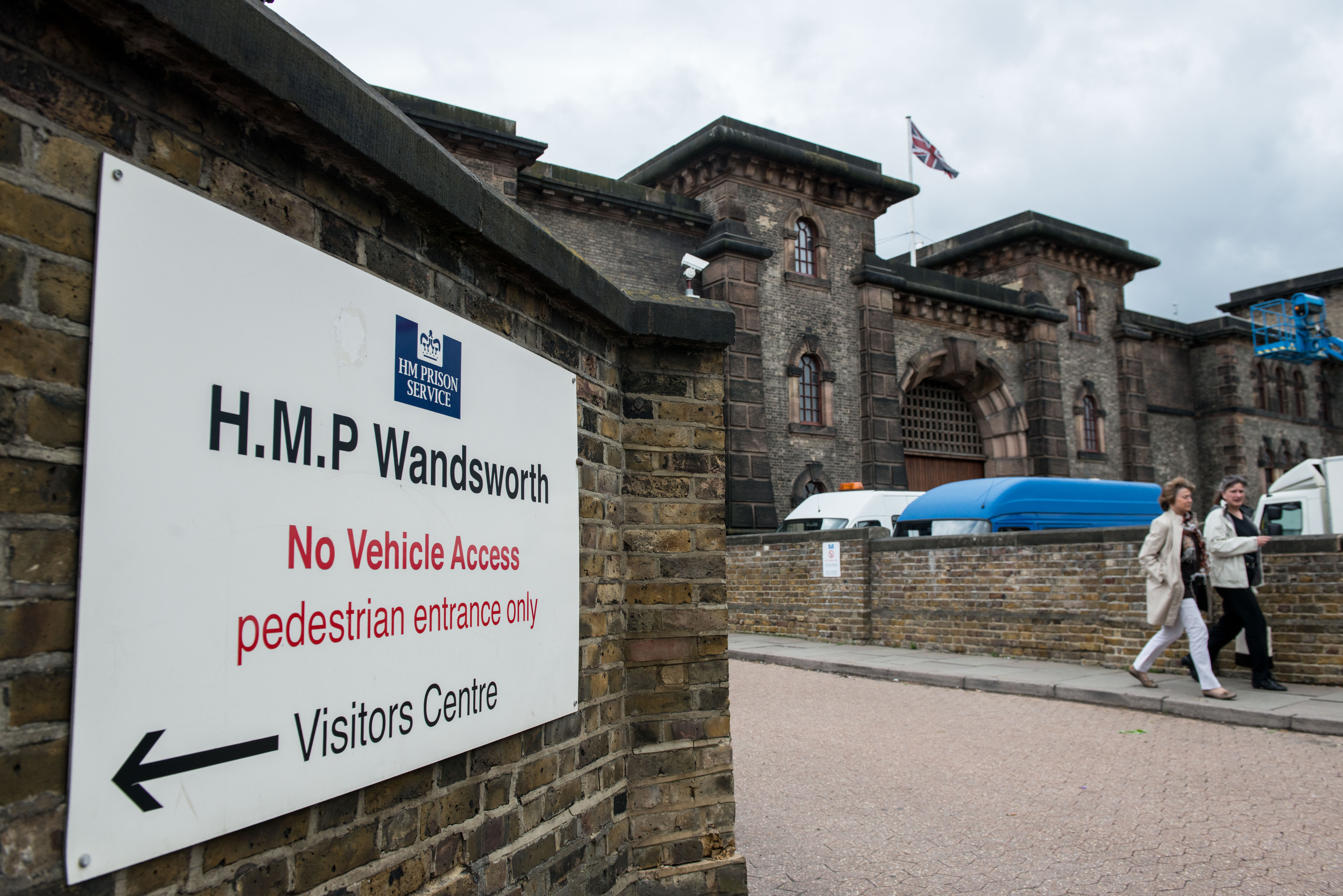

An illuminating insight into one of Britain’s most well known prisons

When a fundraising scam went wrong for filmmaker Chris Atkins, he was sentenced to five years in prison. His new book reveals what life is really like on the inside, writes David Lister

When Bafta-nominated filmmaker Chris Atkins entered into a dodgy fundraising scheme for one of his documentary films, the scam ended in a nightmare. He was arrested, tried and sentenced to five years in Wandsworth Prison. It would have depressed, defeated and possibly destroyed many people. But Atkins turned his experience into something that became revelatory and could yet have a positive effect on government policy.

He kept a prison diary. The diary was published and its paperback version recently went into the bestsellers list. It is an astonishing read, both shocking and bleakly humorous, giving us one of the most illuminating insights ever into what daily life is like in one of our best-known prisons.

Take this entry when he describes how he became a “Listener”, someone who after some training by the Samaritans, engages with fellow prisoners to listen to their problems.

“I’m asked to see a lad called Dean, who is on a monitoring programme for prisoners at high risk of suicide. He has tried to hang himself several times and been placed in K Wing’s observation cell … The walls are bloodstained, and there is barely any furniture. The bed is just a rectangular piece of foam, as even a standard prison mattress is deemed to be too dangerous. A TV sits on a plastic chair in the corner. There’s no privacy curtain, no toilet seat, and nowhere to put toiletries which Dean has arranged on the rim of the loo.

“Dean is only 19. He is wasting away. He hasn’t eaten anything for two days except for razor blades.”

Those last four words, “except for razor blades”, are typical Atkins. A throwaway line that you can’t get out of your mind and makes you sit bolt upright as the daily, routine horrors of prison life are brought home to you via an aside.

Or there was another prisoner he helped on a listening assignment, who surprised Atkins by wanting to talk about quantum mechanics.

He records the meeting in the diary: “'I’m seriously impressed with your knowledge,' I say warmly, congratulating myself on building up such a strong rapport. He nods and leans in conspiratorially. Assuming that he’s finally going to open up about his inner turmoil, I lean in too. Instead, he grins like the Grim Reaper and says, ‘Sing me a song or I’ll slit your throat.’”

I interviewed Atkins on stage at the recent Wells Festival of Literature. It is a wonderful festival in its delightful Somerset setting and one of the very few literary festivals to be staffed entirely by volunteers. But despite the setting, the audience, part present and socially distanced and part online, audibly gasped at some of the detail they were hearing. Atkins said in that interview that daily life was in part tinged with the grim and the grisly, but also in part Monty Python.

Certainly, the humour in the book would not be out of place in the seventies sitcom Porridge.

Here Atkins describes how he “swerved the bang-up” by joining the Liberty Choir. “Affectionately known as Spinsters and Spiceheads [spice is a synthetic form of cannabis], the choir consists of a dozen women of a certain age who visit every week to sing with some of our more troubled addicts.

“Today I go to a practice in K Wing chapel. I’m immediately given a crushing bear hug by MJ, the charming Texan woman who runs the choir. The other women smile at me like psychiatric nurses. More inmates drift in; I count four spice dealers, six spice addicts, and a couple who sit in both camps.”

Yes, one could almost envisage Porridge’s Ronnie Barker in that situation. But as Atkins points out, on-screen prisons, not least the American penitentiaries of Hollywood films, are far from the real thing. He says: “Popular culture gives an oddly false impression of life inside. The on-screen criminals are ripped, tanned and seemingly possess all their faculties. It’s a far cry from the emaciated, spice-addicted souls who surround me in Wandsworth, many of whom are mentally ill.”

Though Atkins has a liberal dose of humour in his book, he told me there was much for him that was far from funny. Perhaps most difficult of all was his enforced separation from his three-year-old son, and the bureaucratic hurdles he had to go through to even have him allowed to visit with his mother. Indeed, the mind-numbing bureaucracy of the prison service is one of the most consistent features of the book.

Popular culture gives an oddly false impression of life inside. The on-screen criminals are ripped, tanned and seemingly possess all their faculties. It’s a far cry from the emaciated, spice-addicted souls who surround me in Wandsworth, many of whom are mentally ill

Atkins cites the palaver over his son as a prime example. He recalls that he was desperate for his son to be brought for a visit. Prisoners in Wandsworth, he was depressed to discover, are only allowed two visits a month, each just an hour long. Nevertheless, when he heard from his partner that she would bring their son to visit, he was thrilled. His diary records what happened next: “I ask an officer if my son has been cleared to visit. The screw looks me up on the prisoner database, and sees that Kit still isn’t approved. ‘We have to do criminal background checks. It can take a few weeks.’ ‘He’s three,’ I reply. The officer shrugs, as if this detail is completely immaterial.”

Government ministers might not lose too much sleep over that, even if the inmates clearly did. But what they should lose sleep over and are quite possibly unaware of, is how little time inmates have out of their cells. Atkins recalls asking an orderly on 4 July if he could enrol on an academic course. “'What education courses can I sign up to?' ‘None. All the main prison wings have just been shut down for the summer. Lack of staff.’ I’m confused. ‘So what do we do?’ He yawns. ‘Stay banged up in your cell. Gonna be like this till August.’ I’m staggered that hundreds of men are simply locked in cells all day. No wonder most of them are going round the twist.”

But the inmates going round the twist didn’t often seem to bother the wardens. Chris cites the time an emergency whistle went off on the wing: “A dozen overweight officers hurtle around like sugar-crazed toddlers, screaming ‘WHERE IS IT?’ Eventually a screw pops up and says ‘Panic over. It’s only a self-harmer.’ The alarm was sounded by a new civilian worker who’d seen a prisoner cutting up for the first time and hit the alarm. As soon as they hear this, the officers all relax and stroll away gossiping.”

Atkins adds that he ended up witnessing so much self-harm that he became completely desensitised to it.

It is, though, the endless bureaucracy that is a key feature of the book and Atkins’ memories of his time in Wandsworth. And it is a weirdly old-fashioned bureaucracy. The digital age does not seem to have entered the prison management system at all, with records, management decisions and prisoner requests stored and communicated on paper.

Take this rather wonderful if totally mystifying notice to which he was directed when he tried to get some warm clothes delivered to him for the winter months.

“Clothing can only be handed in by named contacts of Enhanced prisoners who can only drop off approved items when not coming on a visit between the hours of 10.45-11.30 on Tuesday and Thursday, but ONLY if the prisoner has filled out a new property form which needs to be completed IN ADVANCE to specify dates of drop-off and EXACTLY what is being dropped off (colour, make, size etc) and by whom (name, address, DOB). Property form must be signed by wing staff BEFORE it is sent to property clerk for approval and slip returned to prisoner BEFORE anything is handed in.”

There are over 200,000 children with parents in prison, so denying meaningful contact just breeds a whole new generation of criminals

As Atkins says, it would not have been out of place in a Monty Python sketch. Permeating his memories and his diaries is this black comedy that seeps through his prison diary. He mentions, for example, the time when a prison officer, suffering from depression, hanged himself at home. “I discuss the death with a long-serving prisoner, who shakes his head saying, ‘Tragedy. Fucking tragedy.’ I’m touched that he’s set aside the usual inmate/officer animosity, but he soon puts me straight. ‘Total nightmare. Every time a screw dies, we have an all-day lockdown for the bleedin’ funeral.’”

For a time Atkins gets trained to join a scheme to give certain prisoners more responsibility. He writes: “There are now only four of us in training, and the classes keep veering into outright farce. In our next peer advice lesson, Ruben introduces us to the concept of client confidentiality. ‘This can be broken in certain circumstances’, he tells us. ‘So if you hear anyone discussing criminality, it has to be reported to the authorities.’

“I raise a hand. ‘Given that we live in a Category B prison, we constantly hear talk of law-breaking. If we follow your instructions, we’ll spend every waking hour grassing up our neighbours.’”

Atkins tells me that public school is good training for being a prisoner. The rules and pettiness prepare you well. But startling, sad and funny as Atkins’ memories are, he also offers a cogent manifesto for much-needed change. First, of course, there is a need for a government minister who sticks at the job. During Atkins’ 30 months in jail there were five justice secretaries.

Atkins would want many more specialist mental health units in prisons to lower the rate of suicide and self-harm. He says the plummeting staff numbers among officers also needs to be urgently addressed. “Teachers sit in empty classrooms, as there aren’t enough officers to unlock inmates for lessons. Healthcare is on its knees because prisoners are unable to attend medical appointments. Fewer officers leads to more bang-ups, which directly increases violence.”

He also points out that offenders who leave prison into paid jobs are significantly less likely to reoffend. “Some big employers such as Pret, DHL and Timpson are now deliberately hiring ex-prisoners … More open prisons should be built, which would increase the number of offenders getting paid jobs.”

Rather than being locked in cells prisoners should be getting education. More than half of serving prisoners were excluded from school, so prison provided the opportunity to get the education they missed.

He adds that politicians continually increasing sentences to show they are tough on crime has a detrimental effect. The UK has the highest prison population in the EU and there is no proof that extending sentences acts as a deterrent.

Among many other points in his recipe for change, he says that forbidding adults to wear their own clothes is stigmatising and dehumanising; in-cell telephones should be rolled out nationally, as countless incidents of violence and self-harm are caused by prisoners being unable to use the phone; running prisons with paper-based admin is grossly inefficient, consoles should be fitted in cells so that inmates can electronically access their visits, canteen, menus etc; more medical facilities are needed and officers shouldn’t be able to block hospital visits just to make their own lives easier.

And on a matter close to his heart, visits by family, he adds: “If the authorities genuinely believe that maintaining family ties is the key to rehabilitation, inmates should be allowed a humane allocation of visits. There are over 200,000 children with parents in prison, so denying meaningful contact just breeds a whole new generation of criminals.”

Atkins concludes that the British public has developed “a sadistic mindset towards prisons, and resists progressive policies … But it’s the public that suffers the effects of reoffending, as inmates walk out of the gate more damaged than before they went in, and commit even more crimes. Things can only change when attitudes shift towards more progressive and effective methods.”

‘A Bit Of A Stretch: The Diaries Of A Prisoner’ by Chris Atkins is available in hardback and paperback (Atlantic Books, £16.99)

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks