Can maths produce a truly fair voting system?

The first past the post system has plenty of detractors, writes Mick O’Hare. Can maths offer a better way?

The Electoral Reform Society (ERS), as its name might suggest, is no fan of First Past the Post (FPTP), the system used to elect MPs to the British parliament. But even taking into account its raison d’être – to replace FPTP with a system more representative of how the electorate actually votes – its report into the 2019 general election was particularly scathing.

“Rotten”, “dysfunctional”, “disenfranchisement on an industrial scale”, a voting system that is “morally and politically bankrupt” were just a few of its withering criticisms. Aside from FPTP granting the Conservatives an 80-seat majority on only 43.6 per cent of the vote, the report estimated that 14.5 million people (that’s 45 per cent of all voters; more than it took to elect Boris Johnson’s entire government) cast votes for a non-elected candidate, with as many as a third of the electorate forced into attempting to vote tactically. “FPTP is brutal in denying millions of voters any representation at all,” the report concluded.

And there’s more behind that “thumping” mandate the Tories used to “Get Brexit Done”. It took roughly only 38,264 votes to elect each of the 365 Conservative MPs whereas it took 334,122 to elect each of the 11 Liberal Democrats (who, incidentally, increased their vote share by 4.2 per cent but conversely lost 1 seat) and 866,435 to elect the sole Green MP. And if you think that example is chosen to appeal to the more liberal-minded reader, pity the Brexit Party who garnered 644,255 votes for no MPs at all. Had the Brexit Party been the Tories they would have had 17 MPs while the Lib Dems would have had 96. “Smaller parties always lose out under FPTP,” said the report. And so do parties with a wide geographical spread – the Greens only gaining their single MP because of their strong support in one small area of Brighton.

The failures of FPTP are obvious and although the following example is outlandish it demonstrates how a majority UK government can be elected if only 326 people vote for it. The House of Commons is made up of 650 MPs each elected in their own constituencies. The candidate with the most votes in each constituency becomes its MP. There is no requirement to win 50 per cent of the votes and a solitary voter turning out to support just one of the candidates will suffice. This means that if only one person in each of 326 constituencies votes for Party A and nobody else at all votes, then that party will have 326 MPs and a Commons majority. Meanwhile, in the other 324 constituencies Party B could win each seat with 10,000 voting for it while nobody votes for Party A.

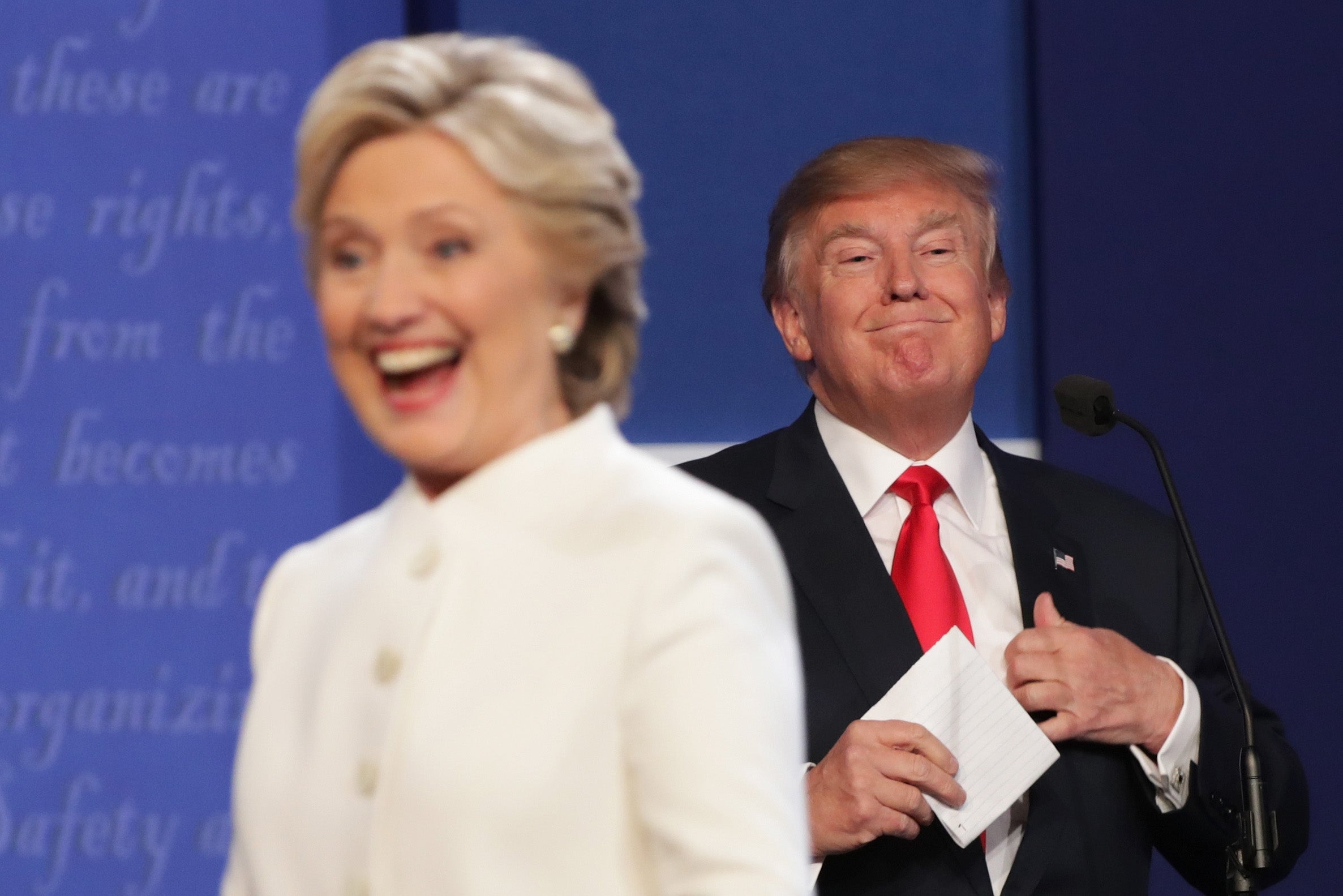

This would mean that although 3,240,000 people voted for Party B and a mere 326 voted for Party A, Party A would form the government. The 1951 general election produced a result along this general template. Labour won a majority of votes nationally but didn’t get to form the government. A more notorious example occurred in 2016 when Donald Trump beat Hillary Clinton to the United States presidency despite receiving 2.8 million fewer votes nationally. FPTP is demonstrably unfair. Even its proponents in the Conservative Party and beyond know it, despite manifesto commitments in favour of retaining it.

And electoral systems have been thrown back into the spotlight recently following the tedious and arcane system used to elect the new Conservative Party leader. Ironically, considering staunch Tory support for FPTP, new prime minister Liz Truss would have failed to make it into the final round if FPTP rules had applied earlier in the contest. As it was she could only accumulate 81,326 votes from a total Tory party membership of 171,437.

Most progressive political thinkers, although not all – John Rentoul The Independent’s chief political commentator has previously made a defence of FPTP in this publication, although to be fair he did denote it the least bad option – believe some form of proportional representation (PR) is the solution: the number of MPs representing each party in parliament should be linked to the total number of votes the party receives nationwide. But with so many different forms of PR, which would be the most popular among voters? Or, perhaps more crucially, which would be the fairest? And at this juncture, it’s worth noting for the sake of clarity that Britain has never had a referendum on PR although you’ll hear some MPs who defend FPTP insisting we have. The 2011 referendum was on whether Britain should adopt the alternative vote system which is about as far removed from PR as is FPTP.

Politicians tend not to base their beliefs on absolutes, relying more on ideology, gut feeling and which policies are likely to amass the most votes. Mathematics is something to be ignored in a world where rhetoric rather than rationality holds sway. Politicians and their supporters are often very passionate about the systems used to elect them – FPTP has many supporters in parliament because that was the very system that put them there in the first place. Likewise, supporters of the various forms of PR are equally fervent. But heartfelt support for a particular voting system doesn’t necessarily mean it is a fair one.

Introducing a 5 per cent cutoff to stop extremist parties often sets the threshold too low but raising this threshold to, say, 15 per cent risks discounting minority parties entirely

So how do we sort the equitable from the biased, the impartial from the partisan? Can the cold logic of mathematics, with its objectivity unskewed by interpretive human notions help? Which system of PR might provide us with results that match the intentions, aspirations and desires of the largest number of voters? In fact, is there a “fairest system of them all” as a politically minded fairytale queen might ask?

Unfortunately, the short answer is no. Well, sort of. New Scientist’s 2010 report into voting systems carried the headline: “The maths of democracy: why fairness is impossible.” Written by popular-science author Ian Stewart, emeritus professor of mathematics at the University of Warwick, it invoked Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem. Effectively this states that any voting system has to abandon at least one criterion of “fairness” in order to work. It is named after American economist and Nobel laureate Kenneth Arrow. An obvious example of the theorem can be found under the system known as the supplementary vote, used to elect mayors in England. Voters give a first and second choice preference. If the leading candidate doesn’t reach the majority threshold of 50 per cent, the top two candidates go through to a second round and second-preference votes are taken into account.

Let’s assume there are three candidates, one from the extreme right, A, a centrist, B, and one from the extreme left, C. B will almost certainly be either the first or second choice for most voters. But if A and C both accumulate 34 per cent of first choice votes and B only 32 per cent, B would be eliminated in the first round of voting despite being the compromise candidate for nearly every voter. Therefore, an extreme party would be elected against the wishes of 66 per cent of voters.

Of course, other systems are available, PR comes in many forms and levels of complexity, and varies depending on whether we are voting for parties or people. The single transferable vote system builds on the supplementary vote with voters ranking all candidates rather than just two, but it suffers from similar flaws. Then there is the Borda count, a points-based system in which voters score their least favourite candidate with 0, their next least favourite with 1 and so on. If there are five candidates their favourite candidate will score 4. It is used in modified form in Iceland and Kiribati. Range voting is similar. Voters give a score to each candidate from 1-10 depending on how much they like or dislike them. The winner is the one with most points. And two-round systems are also commonplace, used mostly to elect presidents as in France.

Additional factors to consider are whether MPs should be elected purely by the number of votes cast for their party (party-list proportional representation used in South Africa and the Netherlands) or should there be a constituency link (the additional member system used in Germany and New Zealand)? There are also questions over whether there should there be a cutoff of, say, 5 per cent to ensure parties representing extreme positions are less like to have parliamentary representation.

Again, maths can find fault with most of these systems. Introducing a 5 per cent cutoff to stop extremist parties often sets the threshold too low but raising this threshold to, say, 15 per cent risks discounting minority parties entirely, negating the purpose of PR (although the disenfranchised 15 per cent could be invited to recast their votes for parties who did make the cut). “A cutoff is not our policy,” says Klina Jordan, CEO of Make Votes Matter (MVM), the national movement for proportional representation in the House of Commons. “In fact, such thresholds have been used to exclude particular ethnic groups from some parliaments, so should only be considered with caution.”

Maths shows that systems in which voters rank candidates or parties by a score fare slightly better – as long as the voter doesn’t try to manipulate the system or, even worse, lie about their preferences. Voters can give more weight to certain candidates inadvertently or deliberately. Range voting (used in modified form to elect the secretary-general of the United Nations) is especially vulnerable to this. In it, voters rank every candidate from 0-10 with the candidate accumulating the highest score being elected. A centre-left voter might award the centre-left candidate 10, the centre-right candidate 5, the extreme-left candidate 1 and the extreme-right candidate 0.

However, if voters aren’t honest and simply give their favourite 10 and the rest 0, then it turns into FPTP in all but name. Or if the voter expects the outcome to be close, even if they prefer the centre-right candidate to the other two, they might deliberately give this candidate a lower vote “just to be on the safe side”. And, in some cases with long candidate lists, voters might simply get bored and just award candidates any old score. Others just vote from the top of the ballot paper downwards so papers which rotate the order of candidates are necessary. The Borda system counters some of these problems by insisting on a progressive, defined scoring system, but doesn’t eliminate them entirely.

Such conundrums are covered by the Gibbard-Satterthwaite theorem which augments Arrow’s. It has many facets, but essentially takes note of the fact that in any system where candidates or parties are ranked, manipulation – even by a single voter – can alter the outcome. It does, however, demonstrate that range voting can be beneficial if only three candidates are standing – however rare that might be in a British general election constituency. If all voters are required to score their favourite candidate 10 and their least favourite 0, then the middle candidate’s score will always fall between these two ranges meaning that the effect of “lying” is greatly reduced.

Maths also shows us that elections tend to become “fairer” the more rounds of voting they have, or at least the candidate who is “disliked least” tends to rise to the top, as each candidate who finishes bottom is eliminated. Tactical voting under this system becomes less important as the choice of candidates narrows until one wins an absolute majority. Its drawback is that the candidate who is favoured by the biggest number of electors is often not victorious, but assuming the intention is to replace FPTP – which always elects the candidate favoured by the biggest number of electors whether or not they have an absolute majority – then that might be a lesser consideration.

FPTP is used for general elections by a falling number of nations and of the major economies only Britain, the US, India and Canada still use it

Another system that, on the face of it, seems appealing, is to offer MPs different voting strengths in parliament depending on how many votes it took to elect them. This would still use Britain’s current constituency and FPTP system, but with a tweak. If, as we have seen earlier, it takes on average around 38,000 votes to elect a Conservative to parliament but more than 860,000 to elect a Green, that should be reflected when the MP votes in Parliament. However, the mathematical drawback here is that this could give MPs from smaller, more extreme parties (the Greens’ Caroline Lucas being an obvious honourable exception) disproportionate influence. “Such a system would exacerbate geographic divides, it would make a minority of MPs excessively powerful and it would do nothing to proportionately represent people who vote for parties with no MPs,” adds Jordan.

It seems that all mathematics does is gives us a democratic headache. In fact mathematician, Donald Sarri of the University of California showed some years ago that you can invent a voting system that produces any result you desire, from any particular voting pattern. Nonetheless, once we have established that PR systems have their flaws mathematically, that does not mean that they do not have huge advantages over FPTP. Moving in the direction of “fairness” even if it is ultimately unachievable has to be a goal worth shooting for.

Arrow also drew up an idealised list of what a voter should expect from any system, including the following: voters should be able to express a complete set of their preferences; no single voter should be allowed to dictate the outcome of an election; if every voter prefers one candidate to another, the final ranking should reflect that. He also noted that if a voter prefers candidate A to a second candidate B, introducing a third candidate C should not reverse that preference (for example, voting tactically for B to stop C).

Arrow was building on what is known as the Condorcet winner criterion, named after 18th-century mathematician the Marquis de Condorcet. In simple terms, this states a winning candidate in any vote should be the one who would win a two-candidate election against each of the other candidates. That would, of course, be the ideal scenario but as Arrow’s own theorem demonstrates, no system has yet been conceived which fulfils his idealised list and the Condorcet criterion.

Add these mathematical impossibilities to the other random influences affecting election outcomes such as the money required to run for office, the near impossibility of being elected without party backing, gerrymandering, a lack of impartial information to allow voters to make informed choices (Brexit anyone?), equal voter distribution, candidates unrepresentative of the communities electing them (race, religion, class) and one might despair for democracy.

Any voting system needs to maintain a balance between the conflicting interests, demands and necessities of a diverse population while maintaining stable and effective government that does not veer to political extremes. Evidence shows that constituency MPs, beholden to their local populations, rather than candidates taken from national lists, aids this. It is one benefit of FPTP most voters in Britain would like to maintain, making the German mixed-member system of voting for a local candidate but also a national party attractive. MVM helped to broker the Good Systems Agreement (GSA) with organisations and parties who want PR. Taking evidence from PR systems worldwide, it sets out the key principles of good voting systems. “The GSA requires local links to constituencies,” Jordan says. But even the mixed-member system throws up what are called strategic voting anomalies due to the way votes are allocated – a vote for your favoured local candidate can still be wasted as it is in FPTP.

And, in the final reckoning, who decides what is “fair”? As Ian Stewart wrote in New Scientist: “Mathematicians have been studying voting systems for hundreds of years, looking to eliminate sources of bias. And yet what they haven’t done is come up with a foolproof answer. With good reason: one doesn’t exist.” Perhaps the best we can hope for is compromise. “Of course rarely is anything perfect, but most voting systems are better than the one we are lumped with,” says Jordan. “But given the principle that votes should count equally, the best approximations to this ideal are PR systems.”

PR might not be the panacea its advocates profess but what is certain is that FPTP has outlived its usefulness. It might have a place in constituencies where all candidates are wholly independent, but in a modern democracy that embraces party politics, it only offers skewed outcomes. In that 2019 general election 53 per cent of voters backed a second referendum or revoke parties yet Brexit “still got done”. A majority opinion on such a fundamental constitutional change which has had significant political and economic effects surely should have been taken into account, yet FPTP allowed it to be ignored with the consequences – for good or for bad and whichever way you voted in the 2016 referendum – we are now witnessing.

“PR alone won’t solve all the problems our democracy faces,” says Mark Kieran, CEO of Open Britain which campaigns for, among other aims, a revamp of the parliamentary voting system, “but it would help move us from the current situation where politics only a minority voted for, become the default. It’s no wonder turnout at elections is so low. Why vote when nobody listens?”

Jess Garland, director of research and policy at the ERS, said at the time of the report that “Three-quarters of all votes were meaningless at the last general election, lost in FPTP. For millions trapped in hundreds of safe seats it’s like the election never happened. Westminster is a system built on unearned majority rule.”

It’s likely that many readers of this publication back some form of PR, akin to most modern democracies. FPTP is used for general elections by a falling number of nations and of the major economies only Britain, the US, India and Canada still use it.

Perhaps of more consequence is that in Europe, only Belarus shares the UK’s enthusiasm for it, while paradoxically the devolved nations of the UK have all adopted some form of PR to elect members. Crucially, there is no evidence whatsoever that it produces a more stable government, one of the totems of FPTP advocates and an argument that the last three years under Boris Johnson and his once 80-seat majority seem to have invalidated completely. “Political scientists have measured outcomes in countries with different voting systems globally and there is abundant evidence that FPTP actually results in worse outcomes – social, environmental, economic – than proportional democracies enjoy,” adds Jordan.

As the ERS report stated: “Of course, not every candidate or party can or should secure representation, but FPTP is brutal in denying millions any representation at all.” If we are to end what Conservative peer Lord Hailsham disparaged nearly 40 years ago as “elective dictatorship” some form of proportional representation might need to be adopted. But mathematics is a cruel scrutineer, showing up the flaws in any form of voting system. We will at some point have to decide just how many of those flaws we are prepared to accept to see the back of FPTP.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments