Van Gogh’s letters: A window into the mind of one of the world’s most troubled artists

Vincent van Gogh might not be known for his writing but, as a new exhibition in Amsterdam shows, they are artworks in their own right, writes William Cook

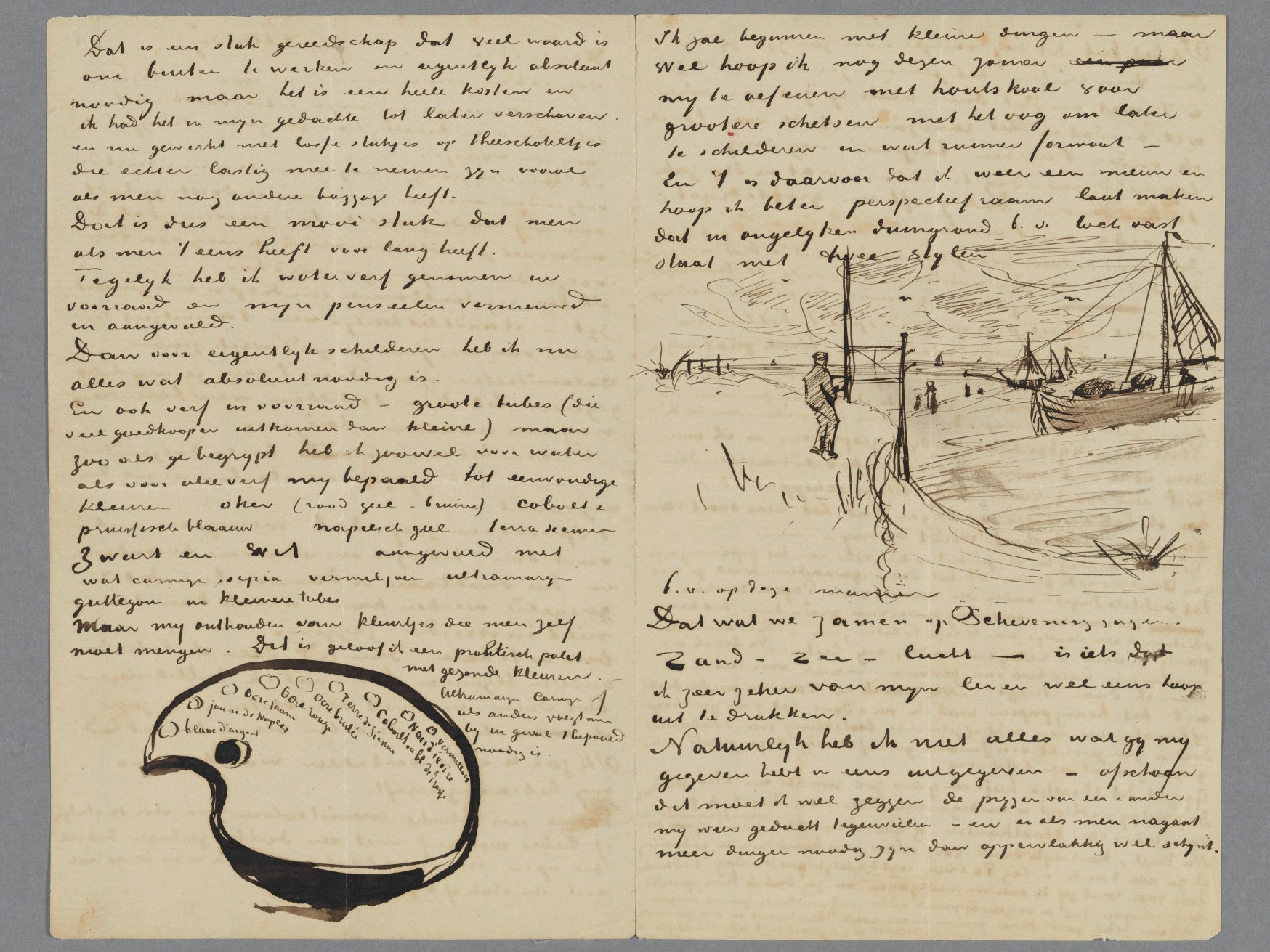

At the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, 40 precious masterpieces are on show together for the first time. But these aren’t paintings, these are letters, by one of the world’s greatest artists. And if you can’t get along to Amsterdam, there’s a new book of his letters you can read at home.

Why read the correspondence of a man who’s famous for what he painted, rather than what he wrote? Because Vincent van Gogh’s letters are artworks in their own right. His pictures would still enthrall us, even if we knew nothing about the man who made them, but it’s his letters that reveal the human being, the face behind the mask. “He really knew how to speak his mind, to shape his thoughts,” says Nienke Bakker, the curator of this show and co-editor of the book. “Even before becoming an artist, he had this talent for evoking a scene or a story.”

Over 800 of Van Gogh’s letters survive, and most of them are here in the Van Gogh Museum. The bulk of this collection comprises the letters he wrote to his younger brother Theo, who bankrolled his career. It’s these letters which form the backbone of this exhibition, and the book. “He has a gripping way of writing,” says Bakker. “It’s about his everyday life, but he writes in such a way that it becomes relevant and recognisable for all of us.”

Van Gogh’s life story has become a romantic fable – the tormented visionary, shunned by polite society, whose priceless paintings were only recognised after his tragic, untimely death. Like a lot of fables there’s some truth in it but, as these letters show, the reality is more complex. Yes, he was deeply troubled and extremely eccentric. Yes, he only sold one painting in his lifetime, and only became famous after he died. Yet there was nothing automatic about his talent – he worked and worked and worked at it. He only had a basic education, but he was a dedicated autodidact – well-read, well-informed, and fluent in three languages (he spoke perfect French and very good English, as well as his native Dutch). He never made a living from his art, but he had many admirers in the art world. In the last few years of his brief life, he produced hundreds of brilliant paintings. If he hadn’t killed himself, aged just 37, who knows what further wonders he might have achieved?

Vincent wrote to Theo throughout his life, but their correspondence really took off in 1880, when Vincent decided to become an artist. To any objective observer, this must have seemed like a daft idea. He’d already failed at three careers: art dealer, teacher, pastor. He’d shown little artistic talent, he had no artistic training, and at 27 he’d left it very late to start.

Theo had a steady job as an art dealer (at Goupil and Cie, the firm that had hired – and fired – Vincent a few years earlier) but he wasn’t powerful or wealthy, merely a regular employee. Nevertheless, he offered to support his elder brother until he was able to pay his way, even though the chances of Vincent ever earning a decent living from his art were slight. Throughout Vincent’s 10-year career, the monthly stipend Theo sent to him remained his only source of income. Vincent never could have carried on without Theo’s support.

Theo sent Vincent a letter every month, together with this monthly stipend. Vincent would reply to thank him and update him on his artistic progress. Although he was frustrated that he couldn’t sell his work, his passion for painting never waned. Theo’s stipend was a lifeline, but it wasn’t a fortune. He lived extremely simply. He worked extremely hard.

Sometimes Vincent asked for more money – which Theo invariably supplied – but it’s clear he didn’t just see Theo as a cash cow. His letters were long and heartfelt. He wrote several times a week. “Vincent was also his best friend, the one he felt closest to,” says Bakker. “Theo was very diplomatic and very thoughtful – he was everything that Vincent wasn’t.”

Unlike his brother, Vincent was compulsive and uncompromising. His letters are equally obsessive, and incredibly intimate. Reading them, you feel you really know him. It’s like being inside his head. He talks about his favourite authors (Dickens, Shakespeare, Victor Hugo), he talks about his favourite artists (Millet, Rembrandt, Delacroix), he talks about religion and philosophy. He’s not interested in politics – he’s far more interested in the big questions: why are we here? What does it all mean?

You’d hardly call it light reading. He has no time for gossip – the laughs are few and far between. Yet he’s fearlessly honest, and that’s what makes him so readable. “Many people find me disagreeable,” he confesses, with admirable candour. “Dealing with people, talking to them, is often painful and difficult for me.”

“He was very driven, passionate, impulsive – he was hard to get along with,” says Bakker, but that manic intensity, which made him so exhausting face to face, made him a compelling correspondent. He pours his heart out about his problems. He holds nothing back.

Theo wasn’t in it for a fast buck, so why did he continue to support him? Because he loved him

With their detailed descriptions of the evolution of his paintings, these letters are a treasure trove for art historians. “No painter has ever taken his readers through the process of his art so thoroughly,” wrote the late, great art critic, Robert Hughes. But for the rest of us, the best thing about them is what they tell us about the man himself. Thanks to these letters, we know him better than any other artist who ever lived. The letters fed the biographies, which fed the films, which fed the legend. He’s become a kind of pop star, the Kurt Cobain of modern art. “The whole image of him as the misunderstood genius who suffered for his art – that image was also shaped by him in his letters,” says Bakker. Sure, without the letters the pictures would still be wonderful, but because of what we know about him from the letters, and the resultant books and movies, we see them in an entirely different way.

Vincent sent his paintings on to Theo, in the hope that he might sell them, but for a long while there was no prospect that Theo would find any buyers for his brother’s work. Vincent’s early pictures were crude and clumsy, and even once he’d found his feet his work remained resolutely uncommercial: weary peasants, gloomy landscapes, all painted in the same rugged, rudimentary manner. Powerful stuff, but not so easy on the eye. Even if you admired them, you wouldn’t want to hang them on your wall.

Clearly, Theo wasn’t in it for a fast buck, so why did he continue to support him? Because he loved him, and because he believed in him. He didn’t just give him the means to paint full-time – he gave him the freedom to paint what he wanted, how he wanted, to develop his own style. “You’ve saved my life,” Vincent told him. “That I shall never forget.” Theo thought Vincent had a gift, but he doubted whether he’d ever achieve mainstream recognition. Privately, he believed Vincent would be remembered as a painter’s painter, “appreciated by some but not understood by the public at large”.

In 1886, Vincent left his native Netherlands and went to live with Theo in Paris. For Theo, this was a nightmare. “My home life is almost unbearable,” he wrote, in an anguished letter to their sister, Willemien. “No one wants to come and see me any more because it always ends in quarrels.” Cooped up in the same apartment for two long years, Theo realised that Vincent suffered from a split personality. “It seems as if he’s two people – one marvellously gifted, tender and refined, the other egotistical and hard-hearted,” he told Willemien. “He makes life hard not only for others but also for himself.”

Yet although Vincent was hell to live with, in Paris his work prospered, and Theo began to think that someday there might actually be a market for his work. “He is certainly an artist, and if what he makes now is not always beautiful it will surely be of use to him later,” Theo told their sister. “However unpractical he may be, if he succeeds in his work there will certainly come a day when we’ll begin to sell his pictures.”

In 1888 Vincent left Paris and went to Arles, in the south of France. It was here that everything came together – an avalanche of amazing artworks, some of the most iconic images in western art. “I have a terrible lucidity at times, when nature is so glorious that I am hardly conscious of myself and the picture comes to me like a dream,” he wrote to Theo. Yet he was working at such a frantic pace that he was bound to crash and burn eventually, and the arrival of Paul Gauguin brought this frenzy of creativity to a climax.

Ironically, it was Theo who arranged for Gauguin to go and stay with Vincent. Vincent had got to know Gaugin in Paris, and now Vincent was living alone in Arles, Theo thought some company might do him good. Vincent welcomed the idea, and at first the two artists got along, but after six weeks Gaugin could bear no more. When Gaugin told Vincent he was leaving, Vincent threatened him with a cut-throat razor, then cut off his own left ear. Theo rushed to Arles to nurse his brother. Gaugin returned to Paris.

I would be very surprised if in time my work doesn’t sell as well as that of others

The letters Vincent sent from hospital are a lot calmer than the ones he wrote before. “I am not, strictly speaking, mad,” he wrote, “for my mind is absolutely normal in the intervals, and even more so than before, but during the attacks it is terrible and then I lose consciousness of everything.”

“His letters from the asylum, unmarred by a single note of self-pity, are among the most lucid and frank ever written by a painter,” observed Robert Hughes.

“I’ve had four big crises in which I hadn’t the slightest idea what I said, wanted or did,” Vincent wrote to his sister, Willemien. Yet he seemed in good spirits. “Every day I take the remedy the incomparable Dickens prescribes against suicide. It consists of a glass of wine, a piece of bread and cheese, and a pipe of tobacco.” Dickens’ remedy delayed his suicide for another year. During that year he completed hundreds of paintings, a phenomenal rate of productivity. In his last few months, he averaged nearly one a day.

Meanwhile, back in Paris, Theo had become a leading figure in the promotion of a new group of artists, the so-called Impressionists. Although Vincent’s work stood apart from theirs, it was similarly radical, and enthusiastically received by fans of Impressionism, and the Impressionists themselves. The influential French art critic Albert Aurier wrote a glowing review of Vincent’s paintings. Finally, it seemed Vincent was on his way.

However Vincent was his own worst enemy, as always. “Please ask Mr Aurier not to write any more articles about my painting,” he wrote to Theo. “I really feel too damaged by grief to be able to face up to publicity.” On 27 July 1890, he shot himself in the chest. Theo dashed to his bedside. Vincent died two days later. In his pocket was an unfinished letter to Theo.

Theo died just six months later, from the side effects of syphilis – a condition which may also have contributed to Vincent’s madness. Vincent’s legacy might have died with him, had it not been for Theo’s widow, Jo, the mother of Theo’s only child, Vincent Willem. She became a champion of Vincent’s work – not just his painting but also his letters. Extracts were published in various catalogues and magazines, and in 1914 she published her own anthology, in Dutch, which she subsequently translated into English. “She felt it was really important to publish them as a book, so that people could really get to know Vincent as a person – not just as an artist,” says Bakker. “She was absolutely crucial in the whole establishment of his reputation.” In 1914, the same year that she published her book, Jo had Theo’s body moved from Utrecht, in the Netherlands, to Auvers, in France, to lie alongside Vincent.

Jo died in 1925, and her huge collection of Vincent’s work, which she’d inherited from Theo, passed to their son, Vincent Willem, who’d been born a few months before his uncle died. In 1973, this collection was rehoused in a new purpose-built Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. It remains there to this day, the largest and most important Van Gogh collection in the world. Naturally, the paintings are the main attraction, but the letters are integral to the collection. “Even if you’ve read these letters over and over again, which I have, you never stop being touched by them,” says Bakker.

Reading Vincent’s letters today, 130 years since he died, they seem uncannily prophetic. “I would be very surprised if in time my work doesn’t sell as well as that of others – whether that happens now or later, well, I’m not bothered about that too much,” he wrote to Theo. “It’s a matter of relative indifference to me whether I live a long or a short time.” He was also worldly-wise enough to know that a deceased artist is far more lucrative than a living one. “People pay a lot more for the work when the painter himself is dead.”

But above all it’s his love for Theo which shines through. “I wish that at the end of our lives we could walk somewhere together, and looking back, say, ‘We’ve done this’,” he told Theo. Both men understood that theirs was a joint venture – the creator and the curator, two brothers against the world. “You don’t know how much he supported me, how he cultivated and encouraged what is good in me,” Theo told his beloved Jo. And in the end his hunch paid off, even if he didn’t live to see it. In 1880, bankrolling Vincent Van Gogh seemed like a fool’s errand – 140 years later, it’s turned out to be the most valuable investment in the history of modern art.

Your Loving Vincent: Van Gogh’s Greatest Letters is at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam until 10 January 2021. ‘Vincent Van Gogh: A Life in Letters’ is published by Thames and Hudson (£30)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks