Freedom of speech in peril: The US Supreme Court vs the First Amendment

The interpretation of this cornerstone of democracy has changed numerous times throughout history. Lynn Adelman explains what it represents in 2020

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The United States Supreme Court has transformed the First Amendment – which guarantees freedom of speech, religion, press, petition, and assembly – into a weapon of the rich and powerful. The new interpretation has thwarted legislative efforts to address the increasing political and economic inequality that afflicts our society. The long-term consequence is a weakening of American democracy.

Free speech is a cause traditionally advanced by outsiders, people espousing dissident ideas or supporting social or economic changes. In the 19th century, the principal proponents of free speech were abolitionists who sought to criticise the southern slaveholders’ attempt to build a pro-slavery antidemocratic state. In his “Plea for Free Speech”, Frederick Douglass proclaimed that “slavery cannot tolerate free speech”, and when the anti-lynching advocate Ida Wells founded a newspaper in Memphis, she named it Free Speech, thus maintaining the tradition of making free speech a central part of the struggle for racial justice.

This pattern continued into the 20th century. During those years, the principal litigants in First Amendment cases in the US Supreme Court were outsiders such as civil-rights organisations representing minority groups. People and organisations who had very little economic, political, or social power typified free-speech litigants, and their challenges sought to alter the status quo.

As a lawyer, I handled several free-speech cases, and all of them fell into this category. One involved a Wisconsin statute prohibiting state employees from seeking appropriations exceeding the amount of their agencies’ official budget requests. The statute, known as the gag law, was designed to insulate legislators from requests for appropriations.

Lawrence Barnett, an associate professor at the University of Wisconsin and the president of his union, challenged the law. Barnett was an outsider, a union activist whose objections leaders in state government had little interest in hearing, but he prevailed in court. A federal judge struck the law down, stating that it prohibited protected speech without an adequate justification.

The court has turned the First Amendment into a battering ram against governmental efforts. It has used the amendment to strike down virtually any governmental initiative aimed at assisting people other than the rich and powerful

Another instance involved a young African American named Todd Mitchell, whose case wound up in the Supreme Court of the United States. Mitchell argued that the two-year penalty enhancer that he received under the Wisconsin hate crimes law for participating in an assault because of anti-white bias punished his thought in violation of the First Amendment. The enhancer was on top of the two-year sentence Mitchell received for the assault.

The Wisconsin Supreme Court struck down the enhancer, but the US Supreme Court rejected Mitchell’s First Amendment argument and reinstated it. Mitchell, a black male challenging a criminal statute that was strongly supported by the civil rights establishment as well as by law enforcement, was even more of an outsider than Barnett.

The outsider status of these free-speech litigants is important because it tells us something about the development of the First Amendment. Many claimants not only sought vindication of their right to free speech but also a form of equality, the right to speak on equal terms as other speakers – speakers who had greater power and status than they did. They sought what might be called the right to expressive equality, urging courts interpreting the First Amendment to pay attention not only to what they said, but also to the economic, political, and social factors that affected their capacity and that of others to engage in expressive activity.

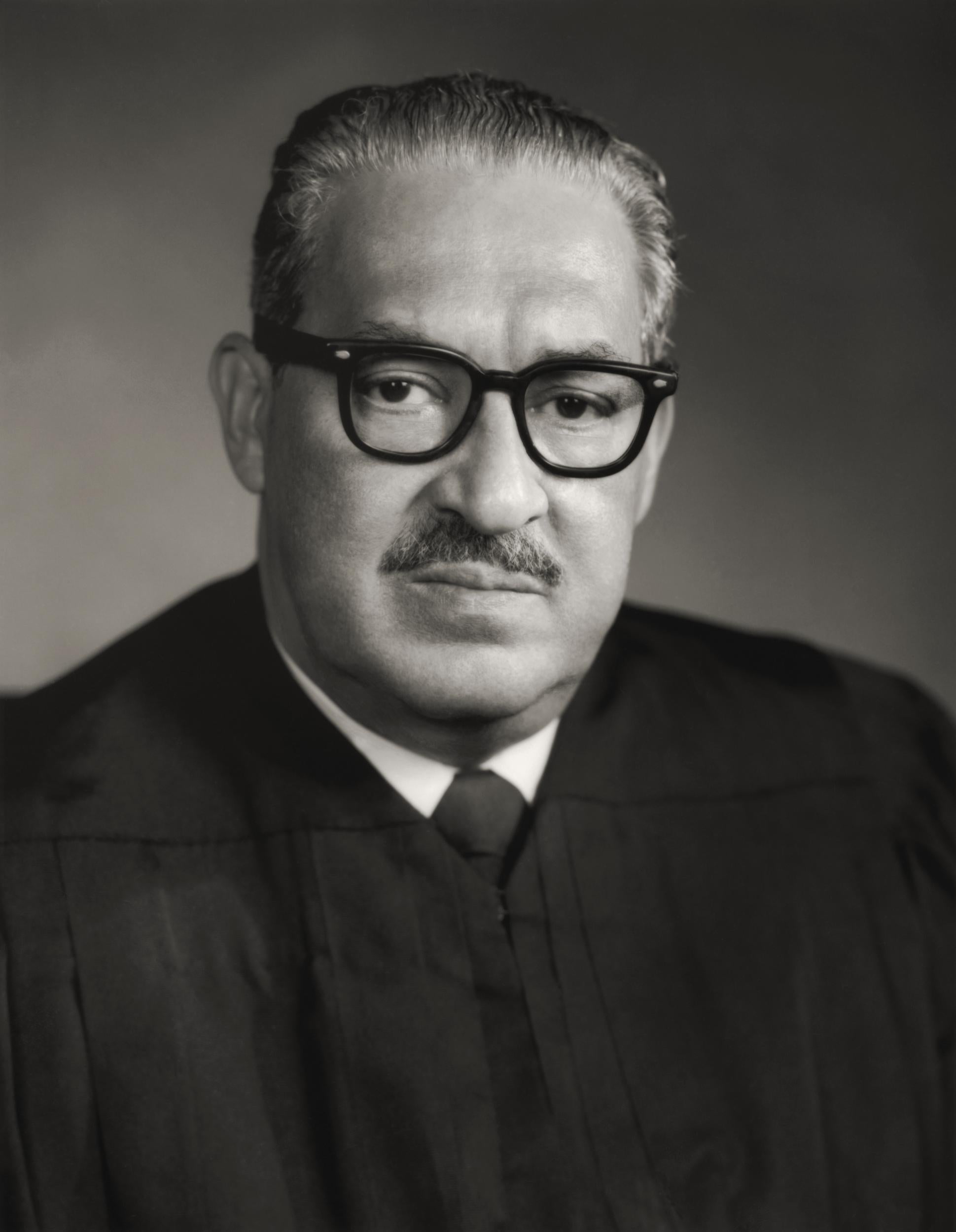

And to some extent they succeeded. In the mid-20th century, in some cases, the Supreme Court recognised that an equality guarantee was implicit in the First Amendment. As Justice Thurgood Marshall put it, the First Amendment guarantees not just freedom of speech but “equality of status in the field of ideas”.

Thurgood Marshall, one of the great champions of free speech, and the first African American to serve on the Supreme Court (1967-1991), consistently emphasised that the main purpose of the First Amendment was to ensure that all speakers have roughly equal opportunity to participate in the public sphere. For Marshall, the key to the First Amendment was not formal equality but expressive equality.

Marshall came from a less privileged background than most Supreme Court justices – and understood that formal guarantees of liberty and equality do not produce anything approaching actual liberty and equality

Thus, in the area of campaign finance, for example, Marshall supported limitations on the political spending of the wealthy, both because of the public interest in protecting democracy against the corrupting effect of big money and because allowing unrestricted freedom to the wealthy would drown out other voices and result in a less diverse public debate.

Marshall came from a less privileged background than most Supreme Court justices and was personally familiar with the economic disparities in American life. He understood that, in the First Amendment context as well as others, formal guarantees of liberty and equality in conditions of substantive economic inequality do not produce anything approaching actual liberty and equality.

Unfortunately, Marshall’s influence on the court was never great, and, beginning in the 1970s, the court began to move further and further away from the concept of expressive equality. The court became increasingly conservative and less interested in promoting open public debate that included the voices of outsiders. To some extent, the problem began in 1976, when the court (then led by Warren Burger) decided Buckley v Valeo, the seminal campaign-finance case.

Buckley recognised only one government interest important enough to justify imposing limits on the First Amendment right to spend money on elections: the interest in preventing corruption or the appearance of corruption. It stated expressly that the government lacked authority to equalise the relative ability of individuals and groups to influence elections. Decades later, the Roberts Court built on Buckley to interpret the First Amendment so as to make it extremely difficult to prevent the rich and powerful from entirely dominating the public sphere.

In the 1970s and 1980s, the Burger Court and its successor led by William Rehnquist made several other decisions that the Roberts Court relied on to redefine the First Amendment. These included decisions extending First Amendment protection to corporate expenditures on state referenda and to commercial speech such as advertising. Decisions like these laid the groundwork for a new approach to interpreting the First Amendment, an approach that did little for the marginalised and disenfranchised, but provided enormous benefits to corporations and other powerful actors.

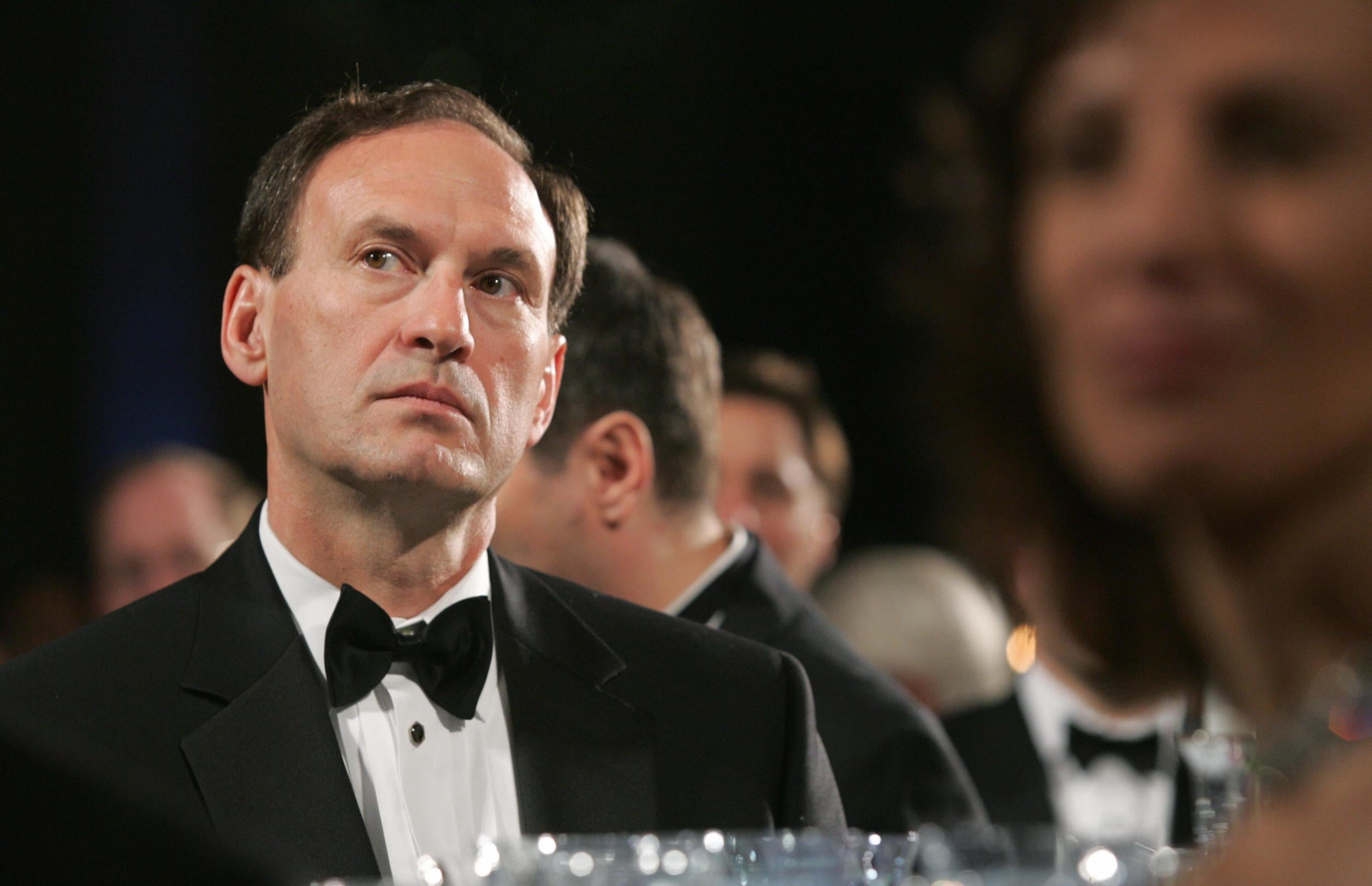

All that was necessary were Supreme Court justices who wanted to make such a change. And it wasn’t very long before such justices came along. George W Bush, whose election as president in 2000 was itself brought about by the court in the infamous Bush v Gore case, was able to nominate both John Roberts, who replaced Rehnquist, and Samuel Alito, who replaced Justice O’Connor. Although Rehnquist and O’Connor were very conservative, Roberts and Alito are even more so.

This brings us to the disturbing story of what the Roberts Court is actually doing to the First Amendment. Probably the best thumbnail description of the court’s jurisprudence is Justice Kagan’s statement that the conservative majority on the court is weaponising the First Amendment. The court has turned the First Amendment into a battering ram against governmental efforts aimed at establishing a less hierarchical and more equal society.

Not only has the court totally repudiated Thurgood Marshall’s ideal of expressive equality, but it has used the amendment to strike down virtually any governmental initiative aimed at assisting people other than the rich and powerful.

Let me provide a few examples. A good place to start is the court’s 5-4 decision in Janus v American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees. In Janus, the conservative majority reversed a 40-year-old decision that public sector unions could collect “fair-share” or agency fees from non-members to fund collective bargaining. After all, non-members benefited as much as members from the contracts that the unions negotiated. To justify the reversal, Justice Alito declared that fair-share fees imposed an excessive burden on non-members’ First Amendment rights.

This was so, according to Alito, because all union speech, even collectively bargaining with employers, is fundamentally political. The court’s analysis flouted precedent, providing government with considerable power over public-employee speech, and indicated a strong hostility to unions. In a powerful dissent, Justice Kagan wrote that the court had unleashed “judges, now and in the future, to intervene in economic and regulatory policy”.

Janus also reflects the court’s powerful animus towards governmental assistance to entities that could challenge political authority. For example, when legislatures enact campaign finance regulations or authorise labour unions to collect a fee from non-members for whom they bargain, they provide more power to those who, as the result of existing economic arrangements, have little.

As the legal scholar Jedediah Purdy sees it, the Roberts Court has enlisted the First Amendment in a crusade to prevent government from making these kinds of decisions, with the effect of transferring the allocation of political power from democratic institutions to markets. And while rules made by a democratically elected government are likely to seek to achieve some sort of rough equality, markets have no interest in equality, and market distributions are, in fact, highly unequal.

Further, by using the First Amendment to prohibit the exercise of power by democratic institutions and leaving the matter to the private sector, the court enhances the already formidable power of a class consisting of the wealthy. The court tries to convey the impression that its approach is neutral and seeks only to prohibit government from favouring or disfavouring a person or group.

The court has made American citizens far less equal in terms of their ability to influence elected officials. Unlike the traditional beneficiaries of the First Amendment, the beneficiaries of the court are the wealthiest people in the country

Its opinions striking down campaign finance regulations, for example, liberally use the language of nondiscrimination, as if by treating corporations and the poor the same, it is striking a blow for equality. But a jurisprudence that totally ties the hands of government does no more than assure the persistence of the inequality produced by the market.

A segment of the oral argument in Janus illustrates starkly how the Roberts Court has enlisted the First Amendment as a weapon against governmental distribution of political power. Justice Kennedy pressed the union’s lawyer to acknowledge that the law requiring payment of fair-share fees increased the ability of the union to engage in expressive activity. When the lawyer conceded the obvious, that the fees increased the union’s assets, Kennedy replied, “Isn’t that the end of the case?” making clear that, as he saw it, a law that provided resources that the union could use for advocacy constituted an automatic violation of the First Amendment.

The court’s weaponisation of the First Amendment has been particularly intense in the area of campaign finance. In 2015 in McCutcheon v FEC, the court rejected, for the seventh consecutive time, a limit on electoral spending on the grounds that it violated the First Amendment. The six cases preceding McCutcheon included the notorious Citizens United decision, which authorised corporations to make unlimited independent election expenditures. In McCutcheon, the court struck down the aggregate contribution limit, which capped the amount that a single donor could give to federal candidates and parties at $123,200 in a single election cycle.

In doing so, the court reinforced its view that the First Amendment is an insurmountable constraint on the power of government to limit the campaign spending of the wealthy. Contribution and expenditure limits are not seen as reasonable efforts to equalise the political influence of different classes of people, but illegitimate attempts to suppress the voices of the affluent.

The court’s campaign finance jurisprudence has led to an enormous increase in spending on elections, most of it coming from the extremely wealthy. The court’s judgments have also made American citizens far less equal in terms of their ability to influence the decisions of elected officials. And unlike the traditional beneficiaries of the First Amendment, the beneficiaries of the court’s judgments are the wealthiest people in the country.

But as Justice Breyer pointed out, the First Amendment does not have to be construed in this extraordinarily individualistic way. Another approach would be to pay attention to the effect of a regulation on the body politic. For example, the reason that we are concerned about corruption, Breyer explains, is not because it is a terrible crime per se but because it undermines our belief in representative government. And when elected officials are selected by and dependent on a small number of affluent people, the same loss of faith occurs.

Statutes that impose reasonable limitations on the influence of wealthy people do not violate the First Amendment, they build confidence in the integrity of our electoral institutions and ensure that citizens are an active and important part of the self-governance project that American democracy represents.

The court has not only weaponised the First Amendment against the power of government to attempt to equalise political influence but also against its power to regulate the conduct of private-sector actors. This is particularly true when the court sees the regulation as conflicting with an important conservative value, such as corporate power or Christian belief. Consider Sorrell v IMS Health, Inc, which involved a Vermont statute prohibiting pharmacies from selling data regarding prescriptions without the consent of the prescribing physicians.

The purposes of the legislation were to protect the privacy of physicians and patients, to protect doctors from being harassed by pharmaceutical company salespersons urging them to make purchases, and to reduce the cost of health care by curbing the disproportionate sale of expensive drugs.

The Court once again chose markets over majorities. Further, the ‘speech’ that the Court presumably protected was not actually speech but the sale of data

As the legal scholar Amy Kapczynski explains, the court’s conservative majority saw this different treatment not as a rational response to a marketplace structured by forces that give profit-seeking actors particular incentives but as legislative interference with the marketplace. In the Roberts Court’s view, the marketplace by definition is a neutral, even benign, space that Vermont was essentially contaminating by discriminating against pharmaceutical marketers.

Once again, the court treated government not as an embodiment of the public will but as a coercive force interfering with corporate rights. Put simply, the court once again chose markets over majorities. Further, the “speech” that the court presumably protected was not actually speech but the sale of data. To the Roberts Court, the First Amendment provides a means of preventing the public from interfering with economic markets.

In Burwell v Hobby Lobby, the Roberts Court provided corporations with yet another gift, this one involving their right to be free from a regulation that the corporation’s owners regard as interfering with their Christian beliefs. While in the hate-crime case, Todd Mitchell’s objectionable beliefs about Caucasians subjected him to a two-year prison sentence, in Hobby Lobby the company’s owners’ beliefs were held to outweigh the requirement in the Affordable Care Act that health-insurance plans offer their female employees insurance coverage of contraceptives.

The court’s conservative majority held that a large secular corporation with over 500 stores and 13,000 employees was a “person” engaged in the “exercise of religion” within the meaning of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, a law designed to protect religious liberty and therefore closely related to the First Amendment. The court then went on to say that providing coverage for health benefits to which Hobby Lobby’s owners objected constituted an excessive burden on the corporation’s religious freedom.

Hobby Lobby received a virtually unprecedented religious exemption from a duly enacted statute, an exemption that resulted in significant harm to third parties, the company’s female employees, who lost an important benefit. Further, although the Hobby Lobby case involved contraception, the religious rights that the decision protects are arguably much broader. Under the reasoning of Hobby Lobby, corporations could bring religious free exercise challenges to numerous laws protecting workers.

Forces on the political and religious right, for example, could argue that minimum-wage laws and collective bargaining violate the teachings of Jesus and the Bible.

Thus the Roberts Court has weaponised the First Amendment against a variety of types of laws that it dislikes: laws that attempt to equalise political influence, laws that interfere with the freedom of businesses to operate as they wish, and laws that arguably impinge on a corporation owners’ Christian beliefs. In the latter connection, I should also mention National Institute of Family and Life Advocates (NIFLA) v Becerra, in which the court’s conservative majority in essence provided more free-speech rights to opponents of abortion than are available to abortion providers.

In a relatively short time, then, the Roberts Court has transformed the First Amendment. The landmark cases that made the First Amendment prominent involved outsiders such as civil-rights activists, public employees, students, and dissidents. Now things have changed dramatically: the Harvard law professor John C Coates IV has shown that First Amendment cases in which businesses are the primary beneficiary have increasingly displaced cases involving individuals.

Prior to the 1970s, only expressive businesses challenging laws that directly impeded their core business were able to convince the court to strike down laws on their behalf, whereas other businesses seeking to achieve deregulatory goals generally were not successful.

Today, however, the cases in which businesses invoke the First Amendment generally involve plaintiffs who are primarily interested in influencing government or increasing their profits or both. In Sorrell, for example, the plaintiff was not interested in vindicating any expressive interest but simply in making it easier to make money. This is a new phenomenon. Not until relatively recently has the court used the First Amendment to strike down a statute of any type, and not until 1965 did the court rely on the amendment to strike down a federal law.

In addition, in cases like Janus, Sorrel, Hobby Lobby, Becerra and others, the Roberts Court has shown how the First Amendment can be used to impede legislation designed to advance social welfare. Freedom of speech, association, and religion were once regarded as effective nonviolent means by which the downtrodden could contest their subordination. But under the current court, First Amendment freedoms have become additional resources available to the wealthy to preserve their advantages.

The unhappy performance of the Roberts Court in the First Amendment area is doubly sad because there is so little that can be done about it. Supreme Court justices have life tenure, and, although the justices now on the court have already done much harm, it is only a fraction of what they might do in the future.

A longer version of this essay appears in Raritan https://raritanquarterly.rutgers.edu

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments