The first federal executions in 17 years were staged for Trump’s re-election campaign

In 1972 the death penalty was effectively outlawed in the US: why then did Daniel Lewis Lee become the first of three men to be executed by the state last week? Holly Baxter explains

In 1972, the United States outlawed the death penalty. Three petitioners – one who had been convicted of murder, and two of rape, in the states of Georgia and Texas – brought a successful case to the Supreme Court arguing that capital punishment constituted “cruel and unusual punishment”.

Notably, the three men who brought their case to court were black, and the justices who decided to vote against further use of the death penalty agreed that its use was not uniform and seemed to be brought disproportionately against people who were poor, black, or members of minority groups. This was important, because it allowed the balance to tip towards “unusual” rather than just “cruel”: for a punishment to violate the Eighth and 14th Amendments in the US Constitution, it has to be cruel and unusual, and any action which involves discrimination based on race, class, religion, gender or any other protected characteristic becomes unusual. Few would argue that the death penalty is not a cruel punishment; indeed, many would argue that that was the point.

The judgment was controversial, and it was split: five justices on the Supreme Court voted to effectively ban the death penalty, and four voted to keep it. The successful five wrote more than 200 pages explaining their decision in full expectation of there being an uproar.

For a brief moment in time, it seemed like the death penalty would become another relic of American history. Take Texas – the state with the most executions – as an example; the state held 45 men on death row and seven in county jails who had been recently sentenced to death by execution when the judgment was made in 1972. By March 1973, the governor of Texas had commuted all these sentences to life in prison, and death row was clear. The same procedure was followed by other states in their own facilities.

Why, then, does the death penalty persist in America to this day?

On 14 July of this year, 47-year-old Daniel Lewis Lee was executed after the Supreme Court rejected a very similar challenge to the one made in 1972. The split of justices, again, was 5-4, but this time not in the petitioner’s favour. This time, they were deciding whether a new method of execution – single use of the drug pentobarbital – combined with the risks of execution during a pandemic, where families may not be able to safely travel to say goodbye to their loved ones or to witness the execution, was cruel and unusual. All things considered, the judges went the other way. Lee died at Terre Haute prison in Indiana, the first prisoner in 17 years to be executed after an informal moratorium on federal executions that ended when Donald Trump came into power.

The specifics of Lee’s case as well as the specifics of the judgment made in 1972 explain why that temporary decision never stuck. In 1972, incarcerated people were being executed by electric chair. The justices who voted in the Supreme Court at the time made clear that their judgment applied specifically to the electric chair method, and to the discriminatory way in which the death penalty was being applied.

Although the petitioners in 1972 were hopeful that judges would go further and declare the death penalty unconstitutional, they chose not to – instead, they agreed that it was being “wantonly and freakishly imposed” and shouldn’t continue in its current form. In other words, they left the door open for the death penalty to continue if states could prove that they had overhauled their practises. By 1974, Texas had started filling up death row again, and in 1977 it approved the use of lethal injection as an execution method rather than the electric chair. So continued an ugly American tradition.

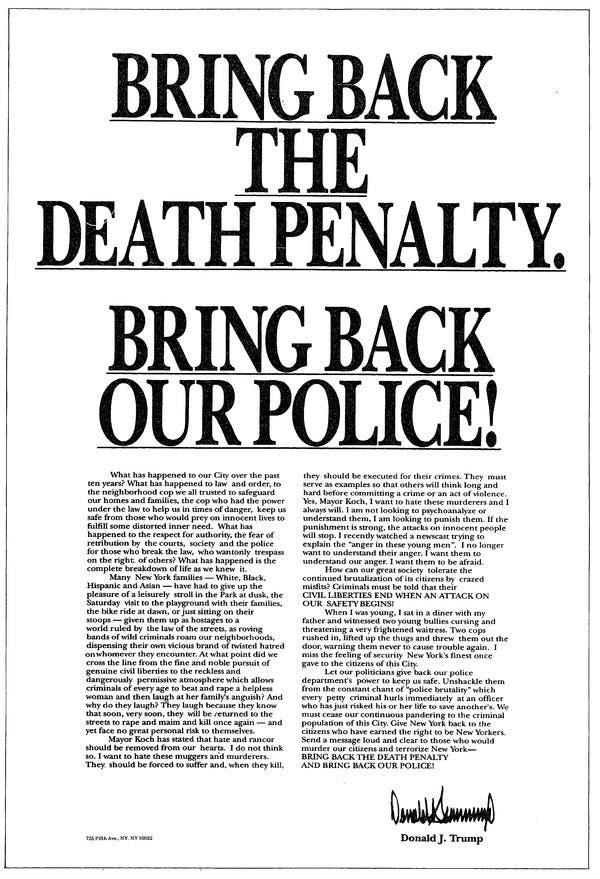

Trump is a lifelong advocate of execution, and even brought out a full-page ad in The New York Times in the Nineties calling for the state of New York to reinstate the death penalty after the wrongful conviction of five black and Latino teenagers known as the Central Park Five

Looking back at what was said in 1972 is poignant, as it shows a moment of huge potential progress that ultimately failed. Two of the five justices who voted against imposing the death penalty said that they thought capital punishment should be eradicated entirely. Justice Thurgood Marshall and Justice William J Brennan argued that the death penalty was contrary to “an evolving standard of decency”.

In the Virginia newspaper The Free Lance-Star, columnist called Barry Schweid wrote that it seemed unlikely capital punishment would start up again in the US after such a judgment. As a sign of the times, the newspaper cartoon below the column shows a disgruntled wife coming in to an empty dinner table and two waiting men, saying, “Oh, for goodness’ sake! I forgot this is the cook’s night off!” Even when casual sexism was the height of hilarity, five middle-aged white men on a Supreme Court packed with legal experts at the end of their careers believed that the US had outgrown such an arcane punishment as the death penalty.

Yet the current president has been a lifelong advocate of execution, and even brought out a full-page ad in The New York Times in the Nineties calling for the state of New York to reinstate the death penalty after the wrongful conviction of five black and Latino teenagers known as the “Central Park Five”. Asked last year if he regretted taking out that ad, considering that we now know the Central Park Five to be innocent, Trump refused to say that he did. In an echo of his words about the Charlottesville white supremacist protests, he simply said: “There are people on both sides.”

The US is now the only “developed” country in the west which still uses capital punishment, and even within the country, it is split down the middle on the issue: 25 states still carry out the death penalty and 25 do not (22 of those states outlawed the death penalty entirely, while the other three have moratoriums presently imposed by their governors.) Executions across the country peaked in the mid-90s, and have now fallen to under 50 a year, but they are still supported in the states where they remain legal. The US government and the US army also retain the ability to carry out the death penalty, which is how Daniel Lewis Lee’s execution came about: it was federally imposed, after a long stint of presidents declining to bring about executions on behalf of the government.

When reading through the Justice Department’s official press release from the day Daniel Lee Lewis was executed, it’s hard not to see his execution and the three expected to follow it as anything other than a PR stunt from a strongman president. The statement mentions Attorney General William Barr – a controversial, “Trump-til-I-die” type figure – a number of times, quoting him as saying: “The American people, acting through Congress and presidents of both political parties, have long instructed that defendants convicted of the most heinous crimes should be subject to a sentence of death.”

At the very top of the release, it is stated that these latest executions concern “four federal death row inmates who were convicted of murdering children in violation of federal law and who, in two cases, raped the children they murdered”.

Bullet-points then further detail the crimes in painful detail; Wesley Ira Purkey, for instance, did not just murder an 80-year-old woman but “[used] a claw hammer to bludgeon to death the woman who suffered from polio and walked with a cane”; Dustin Lee Honken did not just kill a family but killed “a single, working mother and her 10-year-old and six-year-old daughters”. Purkey, who suffered from dementia and schizophrenia, was executed on 16 July, two days after Daniel Lewis Lee; Honken was executed on the 17th; and a fourth inmate on federal death row — Keith Dwayne Nelson — is due to be executed in August. It seems likely that these executions of child murderers will feature in rousing speeches during Trump’s upcoming re-election rallies and presidential debates.

There’s something additionally interesting about Daniel Lewis Lee, and that’s the fact that he is a former white supremacist. Sentenced to death at the age of 23 after a tumultuous, abusive childhood, Lee appears in trial photographs with closely shaven hair and a large, swastika-like tattoo on his neck (it is, according to the Anti-Defamation League, technically a triskele, which has been deliberately modified to look more like a Nazi swastika, and it originated among South African white supremacist groups before becoming popular among their American counterparts.)

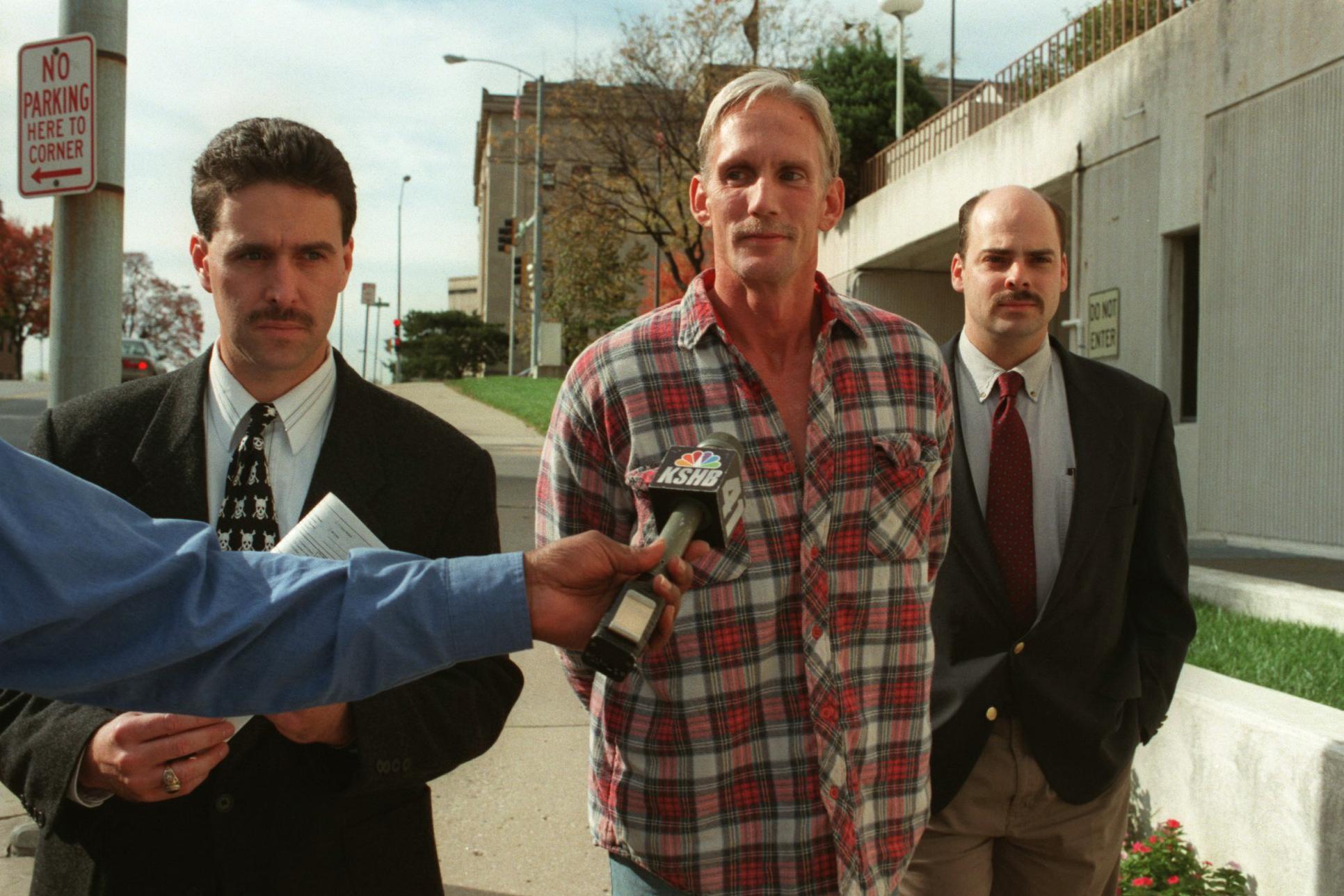

He was recruited by a man called Chevie Kehoe to join a small, violent group of racists called the Aryan People’s Republic (APR) when he was 21 years old. Two years later, he and Kehoe travelled to a firearms dealer called William Mueller’s house in the small town of Tilly, Arkansas, where they procured guns before beating, killing and hiding the bodies of Mueller, his wife Nancy and their young daughter Sarah. Though Kehoe was the ringleader and reportedly admitted to killing eight-year-old Sarah because Lee “didn’t have the stomach for it”, he was given a life sentence rather than the death penalty.

Kehoe’s brother, Cheyne, and his father, Kirby, were both active members of the APR; Kehoe also counted notorious serial killer Israel Keyes as a personal friend. While Lee said after his conviction that he no longer believed in white supremacy, Kehoe has made no similar statement.

Lee is an excellent answer to debate questions about whether Trump condemns white supremacists. What bigger show of condemnation is there, after all, than to put one to death? He’s also an excellent answer to debate questions about family values. Bawdy “locker room talk” about women may be one thing – Trump is well aware that his “grabbed by the pussy” moments still make conservative southern voters queasy – but ending an almost two-decade moratorium on executions in order to make a stand against people who murdered children is another. The announcement of four executions of child killers feels stylistically similar to the appearance of a child who “could have been aborted” at Trump’s State of the Union speech earlier this year. And in the age-old upside-down ideology of “pro-life” Republicans, killing baby-killers just makes sense.

It’s become increasingly obvious that Lee’s death has very little to do with his crimes and a lot to do with what’s convenient right now for Trump. The fact that Kehoe will live a long life in prison sticks in the craw of many a commentator. “Lee’s case demonstrates the unnerving capriciousness of the whole enterprise. By most accounts and several measures, he was less culpable than his accomplice. Yet he’s the one who got executed,” wrote Zak Cheney-Rice, the day after Lee’s death. The Los Angeles Times released an editorial stating that Lee’s execution was “all about politics”, specifically to allow Trump to portray himself as a “law-and-order” leader in the style of other successful Republican presidents.

It’s become increasingly obvious that Daniel Lewis Lee’s death has very little to do with his crimes and a lot to do with what’s convenient right now for Trump

“However one approaches it, the decision to kill Lee derives from a somewhat nebulous and inconsistent set of considerations, the dominant share of which seem politically motivated on the part of federal officials, past and present,” Cheney-Rice continued in his article for New York Magazine, adding that Lee was “a casualty less of justice than of political and administrative whim”.

His words echoed the reasoning of the Supreme Court justices who voted to halt the death penalty in 1972: the punishment is never meted out fairly; the reasoning is often obscure; the people who die at the hands of the state are disproportionately low-income, disproportionately black, or both. Indeed, in the case of Lee, both the lead prosecutor and the judge involved in the case said later that they regretted what had happened in the courtroom, with the prosecutor writing that he still believes in the death penalty but hates its “randomness” as “perfectly illustrated” by Lee’s case, and with the federal judge writing to the then-attorney general in 2015 that he had “the firm conviction that justice was not served in this particular case, solely with regard to the sentence of death imposed on Daniel Lewis Lee”.

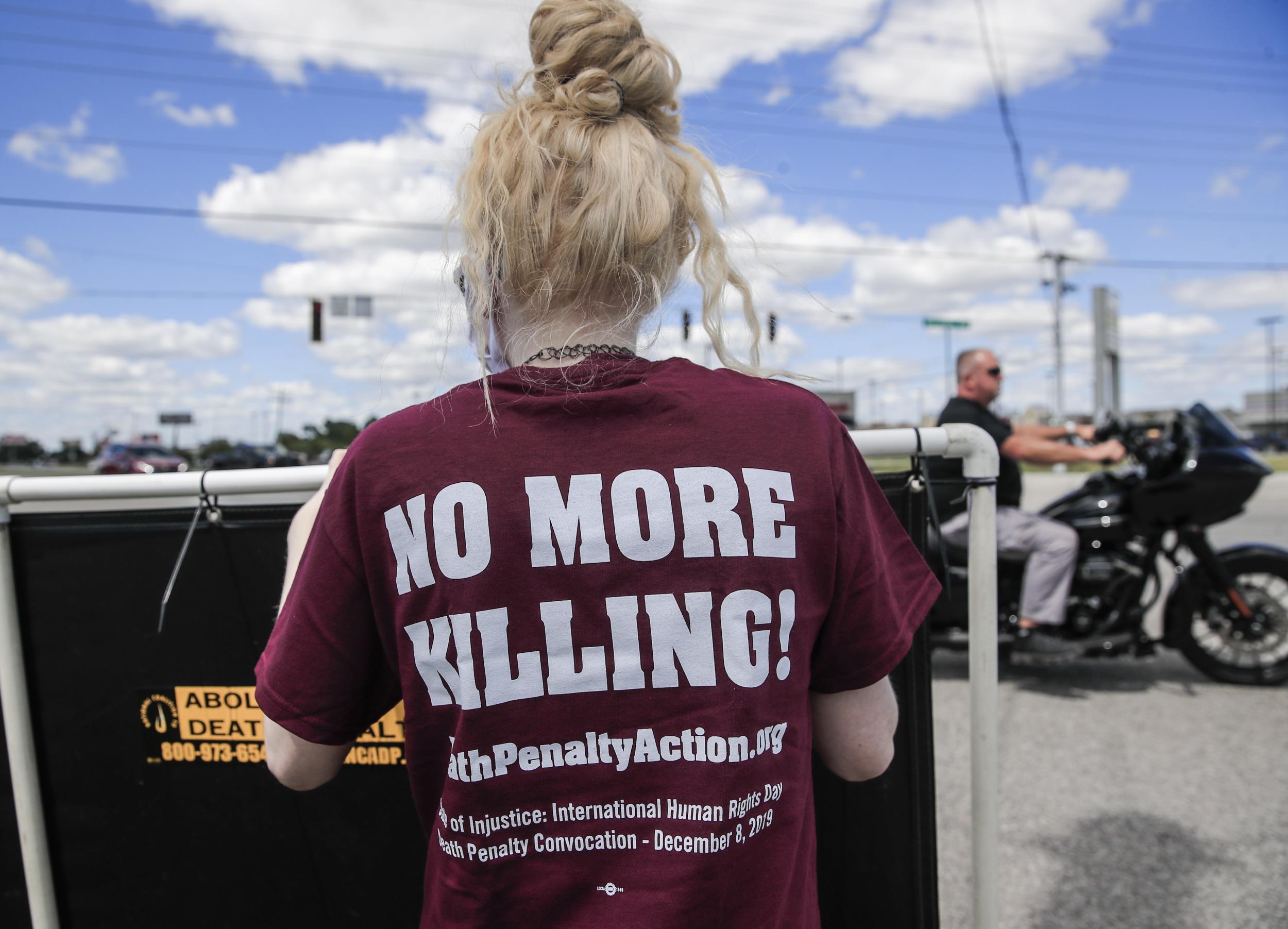

Outside Terre Haute, the prison where Daniel Lewis Lee died on 15 July, protesters in face masks gathered with signs opposing the death penalty as he was strapped onto a gurney and had IVs prepared for a lethal dose of the anaesthetic agent pentobarbital. Further down the road, an unmasked counter-protester stood holding a sign that read: “CONTINUE EXECUTION – EYE FOR AN EYE”.

The case which could have delayed Lee’s execution in the Supreme Court but failed was one that was brought by the killer’s own family, who argued that some of their members – including Lee’s elderly grandmother, who has multiple health problems and is frail – would not be able to travel without risk during a pandemic to be with him when he died. However, they were not the only people who opposed Lee’s execution. Like many victims’ families, the family of William, Nancy and Sarah Mueller did not want Lee killed in their name.

Eighty-year-old Earlene Branch Peterson, mother of Nancy and grandmother of Sarah, is a conservative, a Trump supporter and a resident of the rural, Republican-voting Ozarks. She’s bang in the target demographic for Keeping America Great Again. In a documentary about the murder of her loved ones, she holds up large framed photographs of her granddaughter and “beautiful daughter, Nancy Ann” one by one.

A pink-shirted, blonde eight-year-old grins out of the frame alongside her vibrant, dark-haired mother. Earlene describes her daughter: a gymnast, a horse-rider and a ball of energy with a wicked sense of humour. Standing on the large porch of her countryside home, Earlene describes having to identify the clothes of her daughter and granddaughter after their bodies were found, saying she knew Sarah’s little jacket “with all the buttons and the pens. That was my baby.”

She attended every day of the trial bar one, she says, which featured Kehoe and Lee. Kehoe was “dressed in a suit, like a businessman”, while Lee was scruffy, tattooed and missing an eye — “he looked like an outlaw… you could see the prejudice on the faces of everyone in the courtroom.” Earlene reports the moment when Sarah’s death was described in court: “Kehoe told Daniel to kill Sarah. And Daniel said, ‘I don’t kill children.’ And Kehoe said, ‘Well, I do.’ And he did.” She described herself as “surprised” when the jury returned and the judge announced that Kehoe had been given life without parole, whereas Daniel Lewis Lee was sentenced to death.

Peterson believes Lee should be given the same sentence as Kehoe: “Yes, Daniel Lee damaged my life,” she says. “But I can’t believe taking his life is going to change any of that. I can’t see how executing Lee will honour my daughter in any way. In fact, it’s kind of like it’ll dirty her name. Because she wouldn’t want it, and I don’t want it… Do I think the government should value my opinion? Yes. I’m as much of a victim as Nancy and Sarah was. I think they should value everything I say. I’m the one who lives through it. The government ain’t doing this for me, because I would say no.”

She adds that she thinks Trump is a “God-fearing man”, and that she intends to vote for him in November, just as she voted for him in 2016. But, she says, her voice shaking with emotion: “If I could talk personally to President Trump, I feel he could feel my heart and know that I don’t want this to happen… I believe that putting Daniel Lee to death is not going to help nobody.”

Of course, this documentary was filmed before Lee’s execution was carried out in the early hours of the morning in Indiana earlier this month; the day after Lee died, Peterson’s lawyer simply said she was “heartbroken”. And though Peterson may have been mostly correct when she said that killing Lee would “help nobody”, she was not entirely correct: Lee’s execution could well help the president back into the White House in 2021.

“It is shameful that the government saw fit to carry out this execution during a pandemic,” Lee’s former lawyer, Ruth Friedman, said in the hours after her client’s death. “It is shameful that counsel for Danny Lee could not be present with him, and when the judges in his case and even the family of his victims urged against it. And it is beyond shameful that the government, in the end, carried out this execution in haste, in the middle of the night, while the country was sleeping. We hope that upon awakening, the country will be as outraged as we are.”

Attorney General William Barr released a statement which simply said: “The American people have made the considered choice to permit capital punishment for the most egregious federal crimes, and justice was done today in implementing the sentence for Lee’s horrific offences.” But the question remains: justice for whom, when research continually shows that the death penalty is not a deterrent, and when the family members of the victims oppose the execution? In the case of Lee and his three unfortunate compatriots now scheduled to follow, who really benefits?

In the death chamber Lee implored the media to look further into DNA evidence left out of his trial... His final words were: ‘I’ve made a lot of mistakes in my life, but I’m not a murderer. You’re killing an innocent man’

Behind glass in the death chamber, while 20 people looked on, Daniel Lewis Lee was given two minutes to deliver his final words. He implored the media to look further into DNA evidence, which he says was left out of his trial; one presumes he is referring to a hair which was found in the cap he supposedly wore while carrying out the Mueller killings alongside Kehoe. Independent DNA analysis found that the hair did not belong to Lee, despite the prosecution building a large part of its case against Lee around the hair, but the government opposed reopening his case when the additional testing was done. Lee’s frustrated lawyers said at the time that the government “inexplicably refuses to look for answers where it knows it could find them”.

In the courtroom, Lee’s relationship with Kehoe was described as like a puppy dog following an owner. It was implied that he may have been a willing scapegoat or an uncomfortable bystander. The keys to handcuffs found locked round the wrists of the murdered members of the Mueller family were found in Kehoe’s home. It was also reported from the trial that Kehoe had visited and robbed the Mueller family on his own previously, before returning with Lee on the day of their deaths.

Daniel Lewis Lee’s final words were: “I’ve made a lot of mistakes in my life, but I’m not a murderer. You’re killing an innocent man.” A few seconds later, he raised his head off the gurney to take a final look at the room, and fell silent.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments