‘This is a missing human right’: The men, women and children fighting to revoke their adoptions

For many people who were adopted, the road to reclaiming their birth identity is long, painful and full of bureaucratic hurdles. Natasha Phillips hears their stories

A growing number of adoptees in the UK are battling the government for the right to overturn their adoptions. The movement, which is building momentum, argues that reclaiming a birth identity is a human right.

The movement follows the recent call for a government apology by mothers separated from their babies between the 1950s and 1970s, through forced adoptions. The adoptees leading the cause are the children of the generation of mothers asking for that apology.

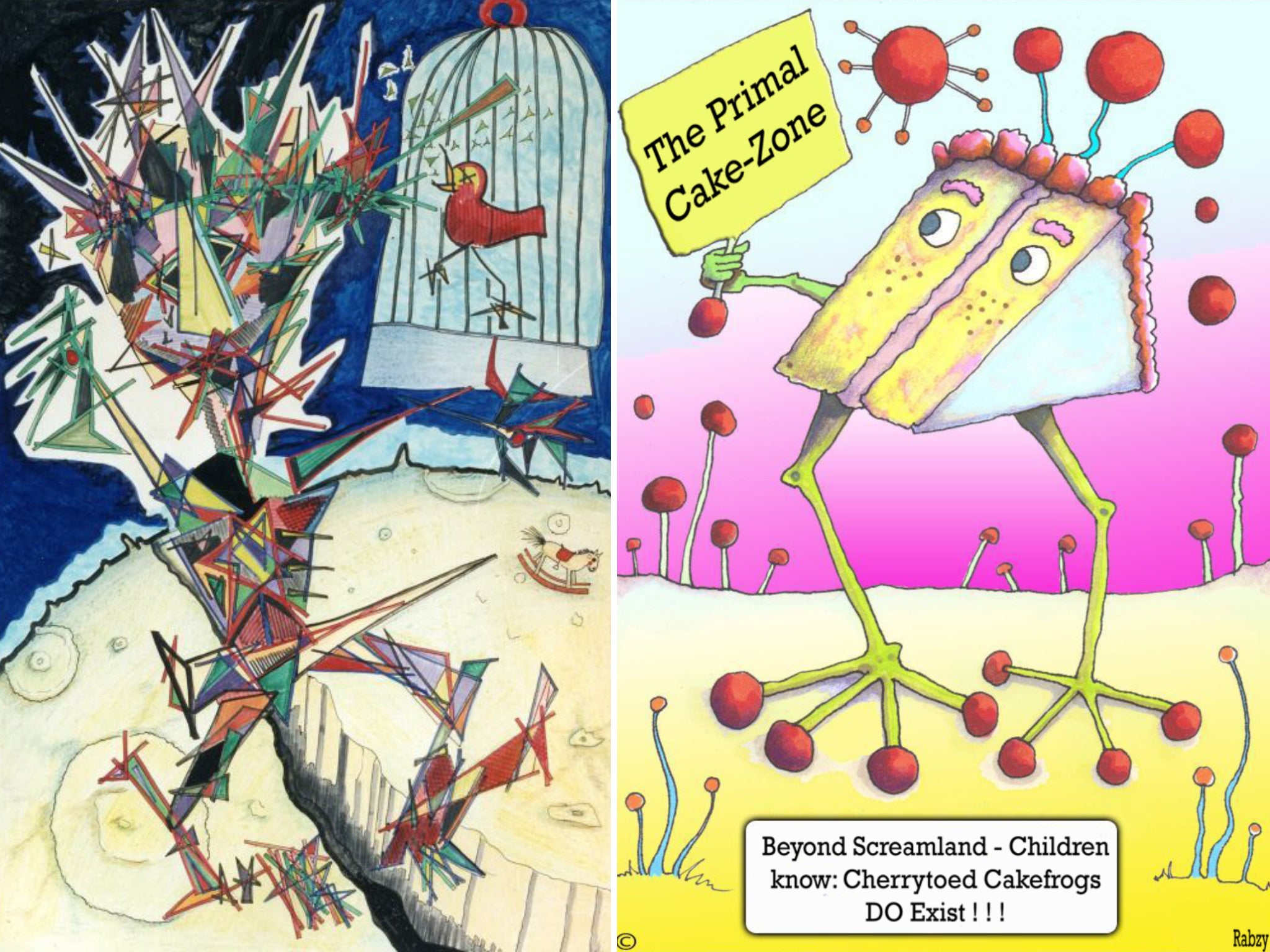

Paul Brian Tovey’s art is an outlet for the pain he has carried all his life. In one drawing titled, Child Abused 1957, an impossible number of deeply coloured triangles pierce a little body looking over at a rocking horse, just out of reach, as they float over a broken moon. A bird in a cage, set at a constant chirp, has ground-in crosses for eyes. A second sketch, layered over a fuchsia pink and pastel blue background shows a frog with cherries for toes, his face made from a slice of cake. It’s a surreal and sumptuous drawing which wouldn’t look out of place in a best-selling children’s book, except for the caption perhaps, which says, “Beyond screamland – children know: cherry toed cakefrogs do exist.”

“Living this life has been terrible. For me, adoption is an artificial process, which has tortured me emotionally, sexually, existentially. I’ve been in a mental hospital twice because of my adoption, and I’ve had to have backup services alongside private treatment,” Paul says.

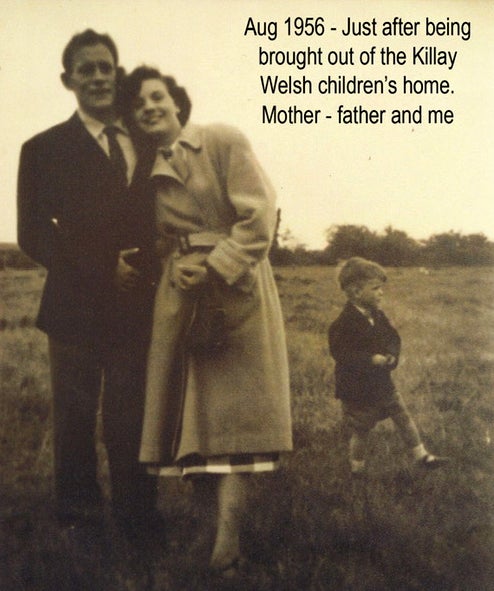

Paul was two years old when the relationship between his mother and father broke down. He spent the next three years in a children’s home, and was then adopted by distant relatives in Birmingham, who abused him throughout his childhood. Paul’s adoptive mother sexually assaulted him from the age of three, a trauma which has left him unable as an adult to have intimate relationships with women.

“My adoptive mother often placed her hands on my penis when I was very young. To have to adapt to an adopter who doesn’t really understand that you need to get back to your mother, who doesn’t understand that your voice is closing down because you’ve been shocked by the person she is, is incredibly difficult.”

Paul was regularly beaten by both of his adoptive parents, on one occasion by his adoptive mother with a fan belt when he was eight, leaving him bleeding, bruised and shaking with fear. At 14, his adoptive father hit him so hard his whole body fell to the floor.

All the adoptees that have spoken to me have said: ‘How is it that the decision to be adopted was made for us – and we had no say in that – and now when we want to have a say, we are still told we can’t have a voice. How is that fair? Where are our human rights?’

“When I was 18 I would often stand in front of the mirror trying to understand who on earth I was. The adoption process caused a major breakdown at 18, I just fell apart,” Paul remembers.

Paul’s nervous breakdown resulted in a hospital admission. Though Paul was unaware of the significance of the admission at the time, it would be the start of a journey back to himself.

“What was interesting about this time was that it also led to a breakdown of my personality, which then reverted right back down to the feeling that I had been abandoned and that my adopters were inadequate. It also led to the understanding and feeling of the awful identification that I’d had to make with my female adopter. Having to take up another form of identity was horrific.”

As part of his recovery Paul went onto Facebook to see if he could revoke his adoption. He was amazed to find a large number of adoptees who had also been abused, trying to get hold of the same information. Paul decided he had to do something to help.

Working with another adoptee, Suzanne Davies, Paul put together a survey to get a clearer idea of UK adoptees’ experiences and how many were looking to revoke their adoptions. The results so far have shocked them.

Of the 90 adoptees who have completed the open survey, almost 27 per cent said they had had a “very negative” adoption experience; 10 per cent said their experience had been “negative”; and almost 19 per cent said adoption had been “somewhat negative” for them. Combined, the survey suggests that 56 per cent of adoptees felt their adoptions were poor.

A further 12 per cent said their adoption had been “very positive”, while 20 per cent cited “positive” and “somewhat positive” experiences combined. The remaining 12 per cent of adoptees polled said they felt their adoption experience was neither negative or positive.

While the survey’s respondents represent all ages – from children old enough to complete the poll to adoptees 65 and over – the largest cohort at almost 38 per cent are men and women aged between 45 and 54, closely followed by 55 to 64-year-olds (23 per cent). Many of these adoptees are likely to be the children of mothers forced to give up their babies during the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s, but the delicate nature of information-gathering among adoptees makes confirming the exact numbers of forcibly adopted respondents difficult.

“I would like to have the option to revoke my adoption,” Suzanne says.

“It’s still a very sensitive subject for my mother. She is watching what’s happening with the mothers asking for an apology, and she is pro-revocation. She says the adoption was the biggest regret of her life, it was forced upon her.”

When Paul and Suzanne delved deeper into the data, they grew more concerned by what they found. A staggering 40 per cent of adoptees who had taken the survey said they had been physically or emotionally abused by their adoptive parents, while 50 per cent said they would revoke their adoptions if the process was simplified. And more than 52 per cent of adoptees said they wanted to live out their lives in their birth identity or another identity they wanted to choose for themselves.

Overturning an adoption by right isn’t possible for adoptees in the UK, who are forced to apply to the High Court in England and Wales, which will then scrutinise the request. Applications very rarely succeed.

Responding to a question on 24 June by The Independent about whether the government would consider making it easier for adoptees to revoke their adoptions, the children’s minister, Vicky Ford, said the government had no plans to do so, and that, “it’s important that the permanent, lifelong nature of these orders isn’t undermined, because an adoption order should provide an adoptee, no matter their age, with the sense of belonging and acceptance that most of us take for granted in our own families”.

For Suzanne, the idea that adoption provides a safe haven filled with kind and caring adults is a world away from her own experience. Suzanne was adopted in 1965 after her mother fell pregnant with her at 18 by her 17-year-old boyfriend, who she loved. Her mother, unable to get permission to marry from her parents who disapproved of the match, had no choice but to give up Suzanne at a time when mothers without husbands were considered “unfit” to parent.

By the time Suzanne was seven-years-old she became severely depressed and was eventually taken to see a doctor. Her adoptive mother would not let her tell the doctor what was wrong.

Her adoptive father was equally hostile. Adding to that trauma, Suzanne was so badly sexually abused by a family member and several strangers that it took her weeks just to tell her therapist, decades later, that she had been a victim of sexual violence.

“The feelings of alienation that were already there, as I never bonded with my adoptive mother and father, were compounded by their parenting of me, and as the years went on and people would ask me about my adoptive parents, I would say they’re not my real parents, they’re guardians. I was never made to feel welcome in the family, I always felt like a lodger,” Suzanne says.

Suzanne and Paul’s experiences, and the experiences of abused adoptees responding to their poll, are not isolated. As well as Paul and Suzanne’s survey, which continues to be accessed and filled out by an increasing number of adoptees, a parliament petition calling on the government to make revocation easier is also gaining traction.

The petition, which to date has gathered more than 400 signatures, asks the government to make it easier for adult adoptees to legally emancipate from their adoptive parents. The petition was created by Jacque Courtnage, who runs Taken UK, a support service for children and parents going through Britain’s family courts. She decided to launch the petition after being inundated with emails by adoptees asking her how to revoke their adoption orders.

As a birth parent having gone through forced adoption, how your child suffers through the adoption process, we know the trauma doesn’t end after an adoption order is made

Like Paul and Suzanne, Jacque thinks adoption revocation is a human right.

“All the adoptees that have spoken to me have said: ‘How is it that the decision to be adopted was made for us – and we had no say in that – and now when we want to have a say, we are still told we can’t have a voice. How is that fair? Where are our human rights?’” She says.

Though Jacque is not an adoptee, she has experienced forced adoption first hand. Jacque and her husband John were accused of child abuse in 2008 after they brought their youngest son, who was nine months old, to hospital having noticed his head was swollen. The doctors found a fracture to his skull and concluded the injury was non-accidental, and that it had been caused by either Jacque or John.

Despite a police investigation finding there was no case against the Courtnages, and evidence that at least one of their two boys could be suffering from Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, a rare genetic disorder which can weaken bones and make them prone to fractures, the family court hearings rumbled on regardless. Both boys were forcibly adopted in 2011.

The case, which was widely reported on by the national media at the time, raised serious concerns about the ongoing use of forced adoption in Britain, a policy employed by an ever-shrinking number of countries around the world who now prefer to obtain parental consent before an adoption can take place.

“As a birth parent having gone through forced adoption, how your child suffers through the adoption process, we know the trauma doesn’t end after an adoption order is made,” Jacque says.

“I think of my own sons. What happens if they come home one day and say, ‘Mum, we want to revoke our adoptions?’ I want to be able to have an answer for them.”

Suzanne believes there are strong parallels between non-recent and modern-day forced adoptions.

“Ultimately for the child, the two policies are the same. Being forced away from your family is debilitating and it’s a lifelong thing. It sets up a problem in the child’s mind, whether they are thinking about it consciously or not, they know they’re not who they’re pretending to be. It messes with them psychologically, and this is happening to a child’s brain while it’s still developing. It’s cruel,” Suzanne says.

While Suzanne and Paul’s survey suggests that the majority of adoptees wanting to revoke their adoptions are from older generations, Jacque says the number of children wanting to revoke may be much larger than previously thought.

“Young adoptees in the UK have told me they are terrified of speaking out because they are scared of upsetting their adoptive families. Some adoptees said they had approached their adoptive parents about revocation. One adoptee was threatened with being ousted from the family unit and disinherited if they tried to make contact with their birth family,” She says.

“Another adoptee told me they made contact with their birth parents when they were 14, and have had a secret relationship with their birth family ever since because they’ve been told by their adopter that they should be grateful they were adopted. It’s very upsetting for them.”

With so many barriers to revocation, adoptees in the UK are reverting back to their birth names using deed poll. For less than £20 children and adults can fill out a form to change their name. The paperwork can take less than three days to be finalised and sent back.

The ability to shed their adoptive names has been a positive step for some adoptees trying to heal from their adoptions, but for others it is not enough. Adoptees who experience abuse at the hands of their adoptive parents are worried about the implications of being legally tied to their abusers.

One adoptee who asked to remain anonymous said he was concerned about unforeseen legal consequences of the adoption, which could place his life in his abusers' hands. One example he gave was a scenario in which he could find himself on life support in hospital with his adoptive parents still listed as his next of kin, giving them the power to end his life.

Naomi Wiseman, a family law barrister at Garden Court Chambers, and a visiting research scholar at Cambridge University, specialising in adoption revocation cases, says legal ties created through an adoption can act as a form of ongoing abuse in certain cases.

“If someone is suffering because of that relationship and has to constantly be protecting themselves by having to be mindful of all these issues, that is in itself a form of ongoing abuse. And if there is an abusive relationship, we know that abusers tend to find whatever avenue they can to continue that abuse,” Naomi says.

Another abuse-related phenomenon which has become a talking point among adoptees on social media in recent years are vindictive adoptions, which occur when a carer pursues an adoption just to keep a child away from one or both of their parents.

Jodi Moore was born in 1973 in Teeside. Her parents separated shortly after she was born, and her mother decided to go back to Northern Ireland to visit family. At the time, Northern Ireland was experiencing the Troubles, a 30-year period of political turmoil in the country marred by violence. Concerned for her safety, Jodi’s grandparents urged her mother to go without her. Jodi was placed in the care of an aunt in Canada, on the understanding that she would be returned to her mother when she came back from Northern Ireland.

Often, adopted people we’ve talked to, even when they’re really positive adoptions, say there’s still a hole in terms of who they are and where they fit in

“My aunt’s side of the story was that she thought my parents might get back together, but until then she kept extending my visa. Then the government told her she couldn’t keep me in Vancouver any longer without adopting me, and she’d gotten attached to me. The adoption was finalised when I was almost four,” Jodi says. “My parents’ side of the story, taken from letters I found after my aunt died, and corroborated by my mother, was that she didn’t know where I was for a long time. I have a letter my mother wrote to my aunt in 1976, the year I turned three, asking her to please return me to her.”

Jodi was never returned to her mother, and her dislike of her aunt and uncle grew stronger as she struggled to survive in a loveless home.

“I didn’t like my aunt and uncle. They were all wrong. I didn’t like their voices or the way they smelled, I didn’t like them touching me, and I didn’t want to be held by them,” Jodi says. “My aunt worked as a secretary at a university’s social work department, so she had access to the university’s doctors and child diagnostic experts. She took me to see them when I was five for a complete evaluation, because I wasn’t bonding with her or her husband. I was always ‘shutting down’ or switching off.”

A therapist tried to explain to her aunt that Jodi’s emotional and behavioural problems stemmed from early childhood disruptions. Jodi’s aunt told the therapist they wouldn’t be coming back to his office.

As a child Jodi created an imaginary world for herself filled with siblings and family pets, in order to try to protect herself from her adoptive parents’ emotional abuse. The abuse included deliberate attempts by her aunt and uncle to keep the whereabouts of her mother and father from her, and blaming Jodi throughout her childhood for their fraught relationship. Jodi is also hoping to find a way to revoke her adoption.

Wiseman agrees with Paul, Suzanne and Jacque that adoption revocation is a rights-based issue, which she says falls within the Human Rights Act’s right to respect for private and family life.

“This is absolutely an Article 8 issue. What I think is difficult here is that adult adoptees can’t rely on current jurisprudence, because unless they can show that the order itself should not have been made at the time, they’re not going to persuade a court to unravel that,” Naomi says.

The law as it stands in England and Wales will only allow an adoption to be revoked if it can be shown that there was either a procedural error made by the court during the life of a case, the local authority failed to process the adoption properly, or new evidence has come to light which could prevent the threshold for an adoption order being met.

“I think it’s highly unlikely that an adult adoptee applying for a revocation many years after the adoption order has been made will be able to find themselves in a position where they can plead any of the three areas of revocation,” Naomi says.

Adoptees who have tried, say, the cost of the process itself is a significant barrier to revocation. While children are likely to get legal aid automatically, particularly if they are already a party to care proceedings in the family courts, adult adoptees are treated differently. If the application does’t get thrown out in the first instance, the cost of seeing the application through is affordable to only a small few.

An alternative solution, Naomi explains, could involve altering UK law around adoption revocation: “Adult adoptees don’t seem to have the agency to sever their legal ties to their adoptive parents. The route we should be going down is whether or not there could be legislative change that is separate from the revocation issue.”

While the courts do not currently recognise that adoption revocation is a human right, the effects of bad adoptions raise important questions about the harm they cause and whether or not that harm is foreseeable.

Anna Gupta is a professor of social work at Royal Holloway, University of London, and a co-author of the UK’s 2018 Adoption Inquiry. The inquiry raised concerns about the human rights implications of adoption practices in England and Wales and concluded that adoption was not a suitable option for most children in need.

“Adoption is not risk free, because of the inherent separation from your birth family, from your history, from both identity and attachment losses. For a lot of children this is complicated by harm being experienced,” she says, adding: “Often, adopted people we’ve talked to, even when they’re really positive adoptions, say there’s still a hole in terms of who they are and where they fit in.”

Gupta is supportive of a simpler revocation process for adoptees. “I think in principle this is a good proposal, especially if it is driven by some adult adopted people feeling this would be beneficial to them. The possibilities and the potential problems would need to be carefully researched and explored including the perspectives of all affected and of course drafted with careful attention to benefits but also potential safeguards,” Gupta adds.

Though no research has been done to explore the connection between severing a child’s bond with their birth parents and the instability and trauma that follows an adoption – most studies tend to assume negative outcomes in adopted children stem from adverse childhood experiences before the adoption – research on separating children from their natural families does exist. And the findings are grim.

Research published in 2017, which was conducted by academics at the University of Michigan using laboratory rats, found that separating newborns from their mothers even for just two hours a day over several consecutive days triggered a rewiring of the pups’ brains. The stress caused by the separation stunted the pups’ development and left them unable to process feelings of fear, or undo the developmental damage caused by the separation. Additional studies of children separated from their parents have repeatedly held the same negative outcomes in both babies’ and adolescents’ cognitive, emotional and physical development.

However, some research suggests that factors like the presence of birth parents and siblings in an adopted child’s life, open communication about the adoption in the home and a secure attachment to adoptive parents may help to protect a child from separation trauma.

“From talking to adopted people in the Adoption Enquiry, identity development is a lifelong process and there is a huge need for post-adoption therapeutic support services through the lifespan,” Gupta says.

Mike Hancock was born in 1962 after his mother had an affair with an older man. Mike’s mother, whose parents felt a child born out of marriage would bring shame on the family, was not allowed to keep her baby. Mike went into a children’s home, where he stayed until he was one year old. His mother fought desperately to find a way to keep him, but as a woman without means she was powerless. Mike was forcibly adopted.

Mike describes his adoptive family with affection. “My experience of adoption was good, but because I had been in care for over a year it took a long time for my adoptive parents to bond with me and me to bond with them. What these parents find is that they have a child in their midst that’s a bit traumatised by what’s happened to them,” Mike says.

Although Mike felt cared for and supported by his adoptive parents, the bound-up trauma of the adoption began to play out in his teens following the death of his adoptive father.

“The family situation deteriorated and I was very cross, not least of all because of the adoption but also my dad dying, and by the time I was a teenager I wasn’t really going home very much. Now I know more about development I know that a lot of adopted teenagers find it very difficult, in terms of their identity and they are angry and confused about things,” Mike says.

Mike now works for PAC-UK, the country’s largest adoption support agency, as head of their adult services in Leeds. The agency has supported thousands of natural mothers and adopted adults who were separated at birth in the 1950s to 1970s, and has helped some of these families to reunite.

“My mum had no means, and it’s interesting with that generation because at the time they were described as mothers ‘relinquishing’ their children, and yet ultimately it was about whether or not you had any choices. My birth mother felt that what happened back then wasn’t right, and she wished she had been given other options.”

Although Mike doesn’t want to revoke his own adoption, he is supportive of adoptees who do and who view it as part of their healing process.

Though the creation of the Adoption Fund in 2016 means adoptees can now access some forms of counselling, the support is limited, and for Paul, Suzanne and Jodi it has come too late. They have had to find their own way home.

This is a missing human right in law for adult adoptees who wish to go back to their own biological or birth identity on official paperwork

Paul’s journey has been unkind. Following a drawn-out battle to get his adoption files from Birmingham City Council, which resulted in a challenge through the Local Ombudsman in 1991 after the council lost his files (they disappeared after the council mistakenly believed that Paul was mounting a legal challenge against them), Paul was able to get some sense of his roots, and his past.

“When you go through quite a number of years of searching, and challenging – all the struggle just to achieve the obvious – it shouldn’t have to be this way. I just want to be me,” Paul says.

Suzanne made contact with her natural mother when she was 24 years old, in 1989, and though the reunion was overwhelming for her, it was what she needed. It took Suzanne longer to find her father, and she was finally able to have a first meeting in February, which went well.

“I sent my dad a message on Facebook and he responded almost immediately. We’ve spoken pretty much every day since then. Since going through a lot of therapy my relationship with my mum is good, and dad was the missing piece of the puzzle,” Suzanne says.

Jodi reunited with her father when she was 12 years-old, after finding out that the man she had been forced to call Uncle George by her aunt, was not her uncle. She bonded with her father straight away.

“I feel as if they kept a blindfold on me my whole life, they knew so much and never told me. It was all about my aunt, no regard for my feelings, and if I wanted to be honest and call her my aunt, she forced me to play along with her fantasy instead and pretend she was my mother,” Jodi recalls.

For some adoptees, reunification can come with setbacks. Mike’s birth mother initially didn’t want to meet with him, which brought old feelings of rejection back to the surface, but over the coming years their relationship flourished. Mike enjoyed a 20-year relationship with his birth mother before she passed away four years ago. He remains in contact with his birth siblings.

“Over the coming years we built up a trust and she became a grandmother to my children and did all that with the blessing of my adoptive mum, which was really good. We spoke about what it was like adopting in the 1960s and that openness helped our relationship a lot,” Mike says.

Jacque’s petition has also helped to break taboos around forced adoptions and revocation.

“One of the adoptees who wanted to revoke her adoption explained to me that her birth mother had never spoken about the adoption. When she told her birth parents about the petition and they started to see that others had been similarly affected, she began to talk to her about the adoption for the first time ever, and she thanked me,” Jacque says.

Paul is a man on a mission. He has sent in submissions about his own experience as an adoptee and the findings of his and Suzanne's survey to parliament’s Joint Select Committee on Human Rights, which is about to launch an inquiry into forced adoptions. He has reached out to the UK’s Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse to argue that adoption revocation is a human right and that the inquiry should look into the issue.

“This is a missing human right in law for adult adoptees who wish to go back to their own biological or birth identity on official paperwork. I want to help other adoptees because these people are suffering. We need to help people so they can live now with their past, by feeling that they’re being recognised, that there is an acknowledgement that adoption wasn’t right for them, and offer them the opportunity to revoke their adoptions and give them back their freedom,” Paul says.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments