Alive and clicking: In praise of the humble typewriter

When an old typewriter unexpectedly came back into his life, David Barnett discovered that these obsolete machines continue to inspire love and appreciation in a digital world

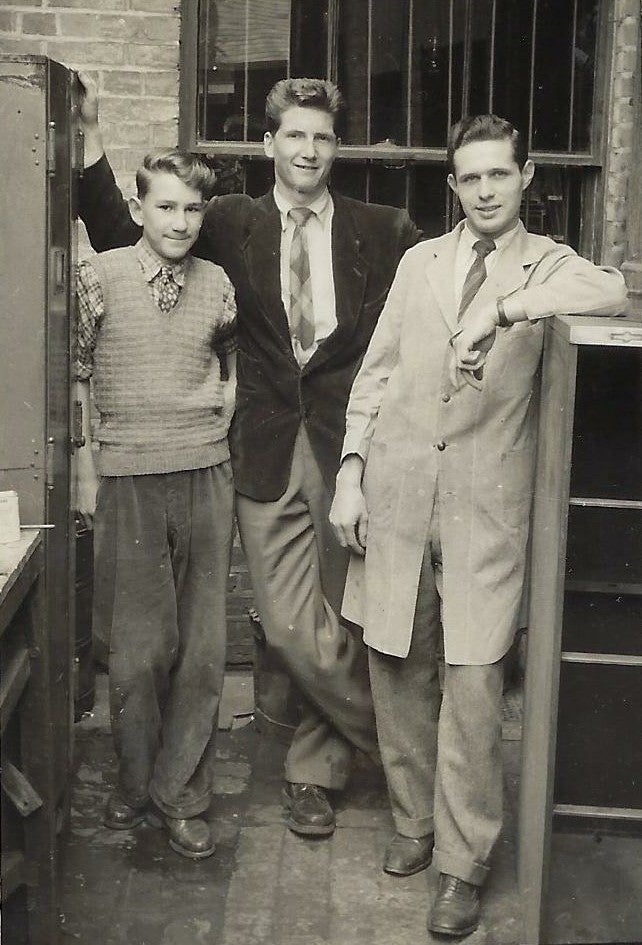

Back in the mid-1970s, George Blackman got a frantic call at his office equipment sales and repair business in Hastings from someone who needed urgent attention to his typewriter.

The potential customer was in Buxted, Sussex, which was a good 40 miles away from George’s workshop, and outside the usual territorial boundaries of his work. But the man on the phone was quite insistent, saying he was in the middle of something hugely important. and after being assured that money was no object with regards to travelling expenses, George agreed to make the journey.

The man had given his name but it meant nothing to George, who arrived and was shown into a bright, airy office in the large house. He was then left alone to work on the Adler machine, pausing only to glance around the study at the rows of books in a multitude of languages bearing his client’s name.

“They were all along the walls on shelves, in Russian and Czechoslovakian and all kinds of languages, as well as English,” says George. “Then I realised where I knew his name from.”

They were all Poldark novels, which George had heard of because the first series of the BBC adaptation of the books written by George’s customer, Winston Graham, had aired on the TV. And from the sheaf of papers by the typewriter, George realised that Graham was in the middle of the scripts for the second series of the show, which starred Robin Ellis and Angharad Rees, and it was exactly the wrong time for his typewriter to fail.

There was something about the way that paper went in as just a piece of paper, but when it emerged to be clamped by the metal rail it became something else

George duly repaired the machine and became Graham’s go-to typewriter repairman for the next dozen or so years.

Money being no object for the author, he could presumably have obtained a replacement machine on which to finish his scripts at fairly short order. That he didn’t, and tracked down George’s expertise to have it fixed, speaks to that strange and beautiful relationship we have with the typewriter.

I was moved to contact George to talk about his 65-year-career fixing typewriters after a visit to my mum’s a few weeks ago. As is traditional when I call round, she has a small stack of things waiting for me, to give me first refusal before they either go to the charity shop or the dump. Sometimes they are old books, bits of train sets, photo albums. This time it was a beige and brown case that gave me a Proustian rush of memory as I unzipped it and lifted the top to reveal the treasure within.

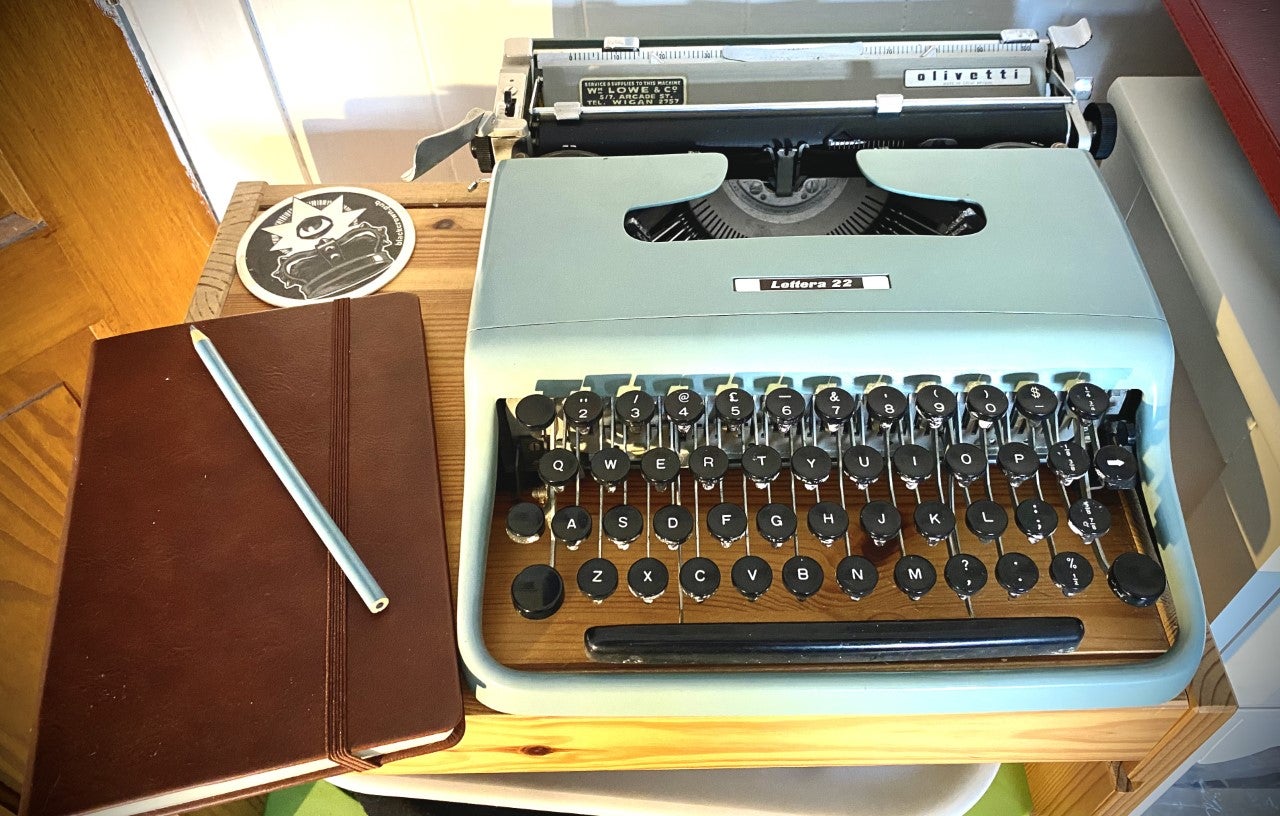

A marine blue Olivetti Lettera 22 typewriter. The one bearing the plate that says it was bought in William Lowe & Co, 5/7 Arcade Street, Wigan. The one I played on from before I can even remember, marvelling at the ordering of the letters on the round keys, pondering at the surely ancient code that demanded they run from Q to W to E to R, not A to B to C to D.

I recalled how I would put a piece of paper between the rubber rollers, turning the wheel with a satisfying, ratcheting sound. There was something about the way that paper went in as just a piece of paper, but when it emerged to be clamped by the metal rail it became something else. Part of the machine. A component in the unique process of creation that could only ever happen on a typewriter.

I would haltingly hit the keys with my forefingers, writing stories and lists and nonsense, my mum teaching me the phrase “The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog” to utilise all the letters on the keys. There was something at once seamlessly mechanical and yet at the same time organically magical about the way hitting a key caused the bars with their inverted letters to snap forward, the inky black ribbon rising to meet it at just the right conjunction, the letters and then the words and then the sentences forming as if out of nowhere on the white paper.

Sometimes she would take it off me and her fingers would dance over the keys like a virtuoso pianist, gathering momentum and rhythm, the clattering of the bars and the ring of the carriage return bell attaining hypnotic, symphonic levels as her head of steam got up.

My mum isn’t a writer, though I suspect she secretly harboured ambitions to be. We just had a typewriter. I think many homes did. For letters and, later, when my dad became self-employed as a builder, for invoices and quotations. I learned to format letters and tabulate and write paragraphs on that typewriter, even before I went to school. I much preferred typing to writing longhand, but the typewriter remained a novelty, little more than a toy, back in those days of the 1970s and into the 1980s.

Boys, generally, didn’t type. Was I planning to become a secretary? No. So there was no real need for me to type, really. Nobody could envisage a future where keyboards would become ubiquitous, and QWERTY no longer a code to be cracked only by the cognoscenti.

When I put pictures of the old typewriter on social media, I was surprised at the response. As someone who writes for a living myself, I find typewriters agreeably and aesthetically pleasing. But I’m not alone. There’s great love out there for typewriters, these metal and rubber and plastic things that have been superseded into obsolescence, yet which still fascinate and thrill.

George Blackman is 82 now and his business is one of the last typewriter repair services in the country. He has handed the day-to-day running to his family, but still does several days a week in the workshops. He’s currently repairing a model from 1911, which he’s basically lovingly rebuilding from the ground up.

It must be a pleasant, dusty, stately thing to do. Surely more a hobby than a job, surely? There can’t be that many people with typewriters, still, let alone ones they need returning to working order?

Perhaps a generation brought up on screens and the dull impotent click of a laptop keyboard find something primal and joyous in the frantic clatter of a typewriter

“We’ve got a huge amount of business at the moment,” says George, speaking from the company’s workshop in Bexhill-on-Sea, to where they relocated in 1995 when needing bigger premises. “We have people coming in every day, either wanting to buy a typewriter or bringing one in for repair.

“Very often they’re finding them in the loft, they’ve belonged to their parents or grandparents and just been left there for years, but now people have a renewed interest in them, they want to get them fixed up and working again.

“I think people kept them just for nostalgia, or didn’t want to get rid of them, and then they maybe stumble across them again and it triggers lots of memories for them.”

People appreciate the look of a typewriter, and many like to put them on display as a feature piece in their homes. But there’s also a rather odd craze among them for young people.

“For the last couple of years we’ve had people coming in wanting to buy typewriters for their children,” says George. “I think the first one I had was a chap who said his 10-year-old son was obsessed by them and he wanted to get him one. I told him that he was buying something that wasn’t a toy, it was something that would last a lifetime.”

Perhaps a generation brought up on screens and the dull impotent click of a laptop keyboard find something primal and joyous in the frantic clatter of a typewriter, at the triumphant flourish of a carriage return, at the sight of the paper creeping upwards, filling almost magically with the distinct font.

Where did the typewriter come from, anyway? Strictly speaking, the first commercial typewriters as we know them know emerged in the 1870s , but the earliest designs for a typing machine predate that by three centuries, when Italian printer Francesco Rampazetto created a machine to imprint letters on paper, which he called the scrittura tattile (tactile writer).

A patent was obtained in 1714 by British inventor Henry Mill for what is recognisably a typewriter, but it was never put into widespread production. It was the turn of the 19th century before there would be a flurry of activity, again in Italy when two separate machines were designed to allow blind people to write, and then in 1829 an American inventor, William Austin Burt, patented a machine he called the Typographer, designed to cut down on the laborious job of writing up official documents.

It would be half a century of tinkering, adjustments and additions to existing technology before Remington began production in 1873 of the Sholes and Glidden Type-Writer, the first to use the name and the originator of the QWERTY keyboard design.

For more than a century the typewriter would be the only way to produce non-handwritten documents. When I was at sixth form in 1986, having decided I wanted to be a journalist, I took lunchtime typing classes, the only boy in a room full of girls, our fingers learning to blindly and unerringly find the keys without looking at them. We would type lines of letters with one finger, and if you have only ever typed on a computer keyboard, you have never know the high intensity workout your left-hand little finger gets from repeatedly hitting the “a” key on a manual typewriter.

George began work in 1965 for an office supplies company in Hastings, of which the sale and maintenance of typewriters was a major part. “I started as an apprentice in the first year, and in this trade in those days you were like a dogsbody, making the tea, sweeping up,” says George. “But I learned by watching the older chaps working, and how they did things, and I started to look at the machines and learned how they worked. Pretty soon I was going into office that had more than 60 machines in them, all needing servicing.”

Not just offices, but to individual clients as well. One who George regularly visited was the journalist and satirist Malcolm Muggeridge, and George says, “I looked after his machines for a long time.”

Imagine the energy imbued into the Underwood typewriter of Jack Kerouac as he rattled out ‘On the Road’ on one long roll of teletype paper in an amphetamine-fuelled frenzy

George rarely calls typewriters by the name we know them, always “machines”. But thinking about the millions of words someone like Muggeridge must have bashed out on his typewriter, it feels like there must be ghosts in those machines. It feels likely that all typewriters are in some way haunted.

If you write something on a laptop, or tablet, or computer, it feels as though that writing is part of the machine, saved to hard drive or cloud, always accessible. Writing on a typewriter is a transient thing, like a short-lived but brightly burning and clamorous love affair. Once the thing is written, the paper is removed from the typewriter and the two things are parted.

But just as the spirits of the dead linger in old houses, perhaps the ghosts of stories haunt the typewriters on which they were birthed. Perhaps it’s like the “stone tape” theory, that suggests ghosts are recordings of the living imprinted on the very walls of their homes. Imagine the energy imbued into the Underwood typewriter of Jack Kerouac as he rattled out On the Road on one long roll of teletype paper in an amphetamine-fuelled frenzy of spontaneous prose.

I saw one of Kerouac’s typewriters once, in his hometown of Lowell, but I don’t think it was the Underwood. I’ve seen other famous typewriters, bristling with the phantoms of the famous works composed upon them. The one Hemingway wrote For Whom The Bell Tolls upon, at Finca Vigia, his Cuban home near Havana. I peered through the window of Dylan Thomas’s writing shed at one at his former home in Laugharne overlooking Carmarthen Bay.

George, too, has handled typewriters with history, with undoubted ghosts. His expertise in a dwindling market of typewriter artisans brought him to the attention of the BBC, and a guest expert spot on their Repair Shop series.

The show features members of the public bringing in their much-loved heirlooms for an overhaul. George says, “This lady in Devon had a machine that was totally seized up and she’d tried to get it fixed but no one could do it, so her husband suggested they call The Repair Shop, and they got me in.

“When she brought it up from Devon it was completely solid, it wouldn’t move at all. But it had an incredible story behind it. She had inherited it from her uncle and it turned out that it was the machine that was used to type up all the proceedings and notes from the formal surrender of Germany at the end of the Second World War.”

Typewriters are beautiful creatures, for things so prosaically utilitarian. Which is why Emma Corfield-Walters has dotted 23 of them around her shop Book-ish, in Crickhowell, Powys, Wales.

It’s a book shop, of course, and there’s an obvious yet pleasing synergy to having typewriters displayed along with the volumes they, at least spiritually, beget.

Emma decided she might like a typewriter as part of her window display, and picked one up from a local charity shop for £30. She says, “It was a massive, old heavy thing but it looked brilliant and caused a lot of interest. Then we moved to bigger premises and I had a few gaps along the top of the bookshelves, so thought it might be nice to fill them up with more.

“I’ve never paid more than £30 for one from a charity shop, and to be honest a lot of them are donated by customers. I suppose my favourite is this big old 1930s Olympia which is amazing, and you can tell it’s been really well used.”

When you look at some of the ones we’ve got in our showroom, they are so beautiful to look at. Apart from their usefulness, they are fantastic-looking things

One customer offered a typewriter that had been her grandmother’s, and when it was in situ, they asked Emma if they could come “and visit her”.

“I was like, ‘please tell me that you haven’t scattered your gran’s ashes in the typewriter…’, they said not but I’m not completely sure, you know.”

Every typewriter has a story, says Emma, no matter how small. “Some of them that come in have just been taken to university in the Seventies and Eighties and been gathering dust ever since, some have come from offices,” she says. “But they’ve all got stories in their somewhere. There was one guy who came in and he had been in the navy, and an aspiring writer, and he travelled all over the world with this typewriter. It wasn’t a lightweight one, either, and it’s amazing to think of him dragging it all over the world while he wrote stories.”

Emma is always in the market for new machines — she’s especially looking for a yellow one and a baby pink one — and she’s been pretty lucky with getting them at good prices.

“The prices are shooting up,“ says George. Six or seven years ago we overhauls an Olympia and it was selling for £30. Now it’s worth nearer £200. The old Imperials are fetching more than £500 now.”

Although essentially a typewriter mechanic, George is also evangelical about the inherent attraction of the machine which has made him his living for 65 years. He says: “When you look at some of the ones we’ve got in our showroom, they are so beautiful to look at. Apart from their usefulness, they are fantastic looking things, the design of the American and German machines is incredible.”

I did my journalism exams in 1989 on a typewriter; not my mum’s Lettera 22, as it was probably in service as part of my dad’s business. But a Grey Fox from WH Smith, probably one of the last modern typewriters produced. By the time I started my first job, in the May of that year, my first paper the Chorley Guardian had just had computers installed.

Back then we called it “the New Technology”, and it revolutionised not just the industry, but the world. Computers were here and they were here to stay. But even the most slickly designed laptop cannot compare to the perfect marriage of form and function that is a typewriter.

Read More:

Many people agree, from actor and noted typewriter aficionado Tom Hanks, who has upwards of 250 machines, to the man wanting to buy one for his curious little son, who had never known a world without touchscreens.

Perhaps, one day, they will fall out of favour again, even as artefacts, and become truly obsolete and forgotten, except as museum pieces, and the distant echoes of clattering keys and ringing carriage returns. Or maybe, with George and his family keeping the machines alive and Emma and many others like her appreciating the aesthetic value of them, the Old Technology hasn’t quite reached the end of the page just yet.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks