Carter, Tutankhamun and the forgotten Egyptian workers

The discovery of the Boy King’s tomb in November 1922 stunned the world. A hundred years later, Rory Sullivan examines its enduring legacy on popular culture and Egyptology

Five words scrawled sideways across an otherwise empty page heralded what would become the most publicised of all archaeological discoveries. “First steps of tomb found,” Howard Carter wrote in his diary on 4 November 1922, four days into an excavation in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings, where he had been working for the previous five years with the financial backing of the amateur archaeologist Lord Carnarvon.

Over the following months and years, the finds from Tutankhamun’s tomb caused a significant global stir. Unusually, the wealth of goods accompanying the young ruler on his journey to the afterlife had largely been undisturbed by grave robbers, owing to the chance construction of necropolis workers’ huts above the site’s entrance during a later dynasty.

So it was that the only more-or-less intact royal burial ever discovered from ancient Egypt yielded up its treasures: a solid gold coffin, abundant jewellery, royal chariots, faience shabti, a panoply of divine statues and much else.

Carter, Carnarvon and “Tut” quickly became household names, while “Tutmania” swept across the world, spawning wave after wave of Pharaoh-inspired products, from board games to high-end fashion. Even now, a century of Western mythologising later, the allure of the Boy King’s golden treasures and their hold on the popular imagination appears not to have lost its grip.

But all this was to come. In early November 1922, Carter jotted down his preliminary findings, covered up the traces of what he had found and, sensing the importance of what lay beneath the earth, sent a telegram to his patron, urging him to hurry to Egypt.

Daniela Rosenow, a German Egyptologist at Oxford’s Griffith Institute, thinks Carter’s elation in that moment is visible in his handwriting.

The co-curator of the Bodleian Libraries’ Tutankhamun: Excavating the Archive exhibition points to the five-word sentence the British archaeologist entered in his diary. “It’s the only time he wrote that way across the page. And having learned a few things about English society, I think this is the maximum you can get an English gentleman to convey his feelings,” she tells me. “His excitement is expressed in his handwriting.”

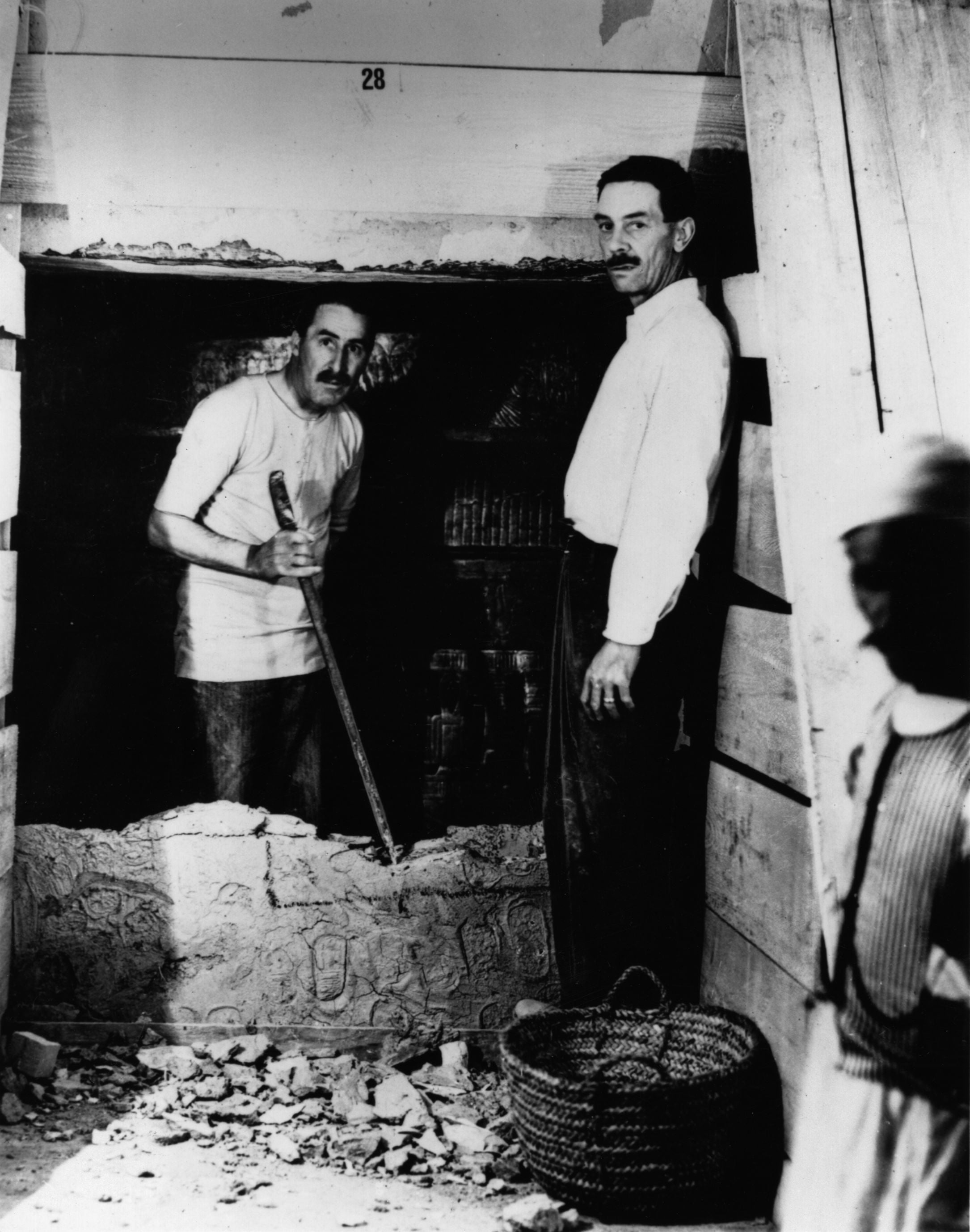

What follows is well-known. After Carnarvon arrived in Luxor, headed to the west bank of the Nile and travelled up into the hills, Carter bored a peephole through the tomb’s exterior wall on 26 November, spying some of its gleaming contents, which then took dozens of people a painstaking 10 years to record, preserve and pack off to Cairo.

Although Tutankhamun’s gold mask soon became the defining image of the 18th-dynasty Pharaoh’s burial, it was only uncovered in 1925, such was the care taken to catalogue the antechamber and the other preceding rooms. Carnarvon, who had financed the discovery, sadly never lived to see it. His health deteriorated due to an infected insect bite and he died in early April 1923 of pneumonia, prompting speculation about the curse of Tutankhamun. It is thought this sensationalist story was created as a means for other newspapers to cover events in Egypt, in their collective frustration that The Times held the exclusive rights to report on the discovery of the Boy King.

George Carnarvon, the current earl, says his great-grandfather, who was a keen traveller and photographer, first grew interested in Egyptology after visiting the British-occupied country in the 1890s and early 1900s. “He was fascinated by the area around Luxor and wanted to get going as an excavator.”

His first foray into archaeology was not successful, but it didn’t dent his enthusiasm. “All they found having moved a vast amount of earth was a mummified cat,” his great-grandson says with a chuckle from Highclere Castle, the real-life Downton Abbey. He adds that his relative worked closely with Carter for years, but almost pulled funding before the 1922 discovery, due to their lack of major finds in the Valley of the Kings. However, the earl was persuaded to reconsider.

There are so many Egyptians currently leading excavations within Egypt. And they are making great contributions and working very hard to reclaim the narrative

Carter’s entry into archaeology started in a very different way to Carnarvon’s. The son of an artist, he was employed at 17 by what is now the Egypt Exploration Society (EES) to trace inscriptions on a dig in Egypt. His own artistic qualities – particularly his skills as an epigrapher – were of enormous benefit to him in his later archaeological work, according to Carl Graves, the director of the EES, whose love of Egyptology started when he saw Tutankhamun replicas on display in his home town of Hull as a child.

“Had it not been Howard Carter leading the team that discovered the tomb, maybe we wouldn’t have had the standard of records that we have,” Graves says. “He was well equipped with the skills to put together a very scientific excavation.”

This was not the perception of Flinders Petrie, one of the field’s greatest pioneers, several decades earlier. In a late 19th-century letter on display in the Oxford exhibition, he gives his first impression of the young Carter. Failing to grasp his potential, the veteran archaeologist describes him as “a good-natured lad”, before suggesting “it is of no use for me to work him up as an excavator”.

For all the focus on Carnarvon and Carter, Tutankhamun’s tomb is of course far more than the tale of two colonial-era British men. “Archaeology is never the story of one heroic man. It’s always a team effort,” says Rosenow.

There are plenty of other Egyptologists who were integral to the success of the project. They include archaeologists like Alan Gardiner, Arthur Mace and Alfred Lucas, and the photographer Harry Burton.

The most glaring omission from the Tutankhamun narrative, however, is the vital work performed by hundreds of Egyptians over the decade it took to clear the tomb. Their contribution has been widely overlooked and most of their names still remain unknown.

“We only know the names of four foremen Carter employed because he lists and thanks them in his book,” says Rosenow. Tutankhamun: Excavating the Archive mentions them – Hussein Abu Awad, Hussein Ahmed Said, Ahmed Gerigar and Gad Hassan – and displays, as its centrepiece, a photo of a young Egyptian boy wearing some of the jewellery found in Tutankhamun’s tomb.

However, the Oxford exhibition – focused as it is on Carter’s archive, which was donated to the Griffith Institute by his niece Phyllis Walker – largely dwells on his and his Western peers’ drawings, photographs, notes and excavation cards. “What you see here is only one side of the story. It’s a very partial view, it’s the view that we can offer based on the English records,” Rosenow notes.

Heba Abd el Gawad, an Egyptian Egyptologist, says the lack of Egyptian names known from the dig speaks volumes. “They went unrecorded. Foreign archaeologists didn’t think they were important enough to record their names,” she says.

The academic sees this slight as part of a wider pattern of exclusion. “Ancient Egypt is more or less represented as an unclaimed culture that has no connection with the contemporary communities in Egypt. That has a lot to do with the colonial foundations of Egyptology, and the colonial lens and framing through which Egypt continues to be seen.”

“Ancient Egypt is not a Western story. It is an Egyptian story – geographically, socio-politically. But the Egypt you see in foreign museums or in Western media is not the Egypt that lives within us,” she adds.

To counter what she calls the wrongly “orphaned culture” of ancient Egypt, Abd el Gawad runs Egypt’s Dispersed Heritage project, which promotes contemporary Egyptian voices in museum collections outside the country.

Instead of the usual emphasis on Carter and Carnarvon, Abd el Gawad wants people to shift their attention for the centenary. For a start, she thinks people should remember some of the less positive aspects of the story, noting how Carter spirited a few of Tutankhamun’s grave goods out of Egypt. After his death, these were returned by his estate.

Abd el Gawad also wants people to reflect on the success Egyptian anti-colonial activists had in 1922 in gaining more autonomy from the British, 31 years before their country gained full independence. And to understand that such campaigning also resulted in a change to the antiquities law, which meant that Tutankhamun’s burial goods remained in Egypt.

Enough credit is also not given to prominent Egyptian archaeologists today, she says. “There are so many Egyptians currently leading excavations within Egypt. And they are making great contributions and working very hard to reclaim the narrative.” One of their best recent finds was Ola el Aguizy’s discovery last year of the sarcophagus of Ptah-em-wia, Ramesses II’s treasurer, at Saqqara.

Toby Wilkinson, an Egyptologist at Cambridge University, believes his Western-centric field is slowly changing. “It is beginning to be remedied now and there are some good studies that are bringing Egyptian names to the fore,” he says.

Returning to the events of 1922, the author of Tutankhamun’s Trumpet: The Story of Ancient Egypt in 100 Objects says the unearthing of the young Pharaoh’s burial helped the Egyptian nationalist cause. Its leading figures used the discovery to highlight their country’s spectacular past. “The after-effects of Tutankhamun’s discovery took 30 years to fully play out, but it planted the very fervent seeds that Egypt’s future belongs to the Egyptians.”

The tomb also sparked the West’s obsession with ancient Egypt, he says, describing Carter’s find as “the greatest archaeological discovery of all time in terms of the sheer volume and the impact.”

He believes Tutankhamun continues to resonate with people on a very human level because it has all the hallmarks of a good story. “It’s very important for historians to bring the ancient world to life in a way that connects with people today. And I think the story of the Boy King, his extraordinary life, his tragic death, amazing burial and rediscovery has all the elements you need to reach across those centuries, those millenia, and bring the modern reader into closer proximity with the ancient world.

“It is and remains a great touchpoint. If people have heard of anything to do with ancient Egypt, it is pyramids, mummies, Cleopatra and Tutankhamun. It’s a great way of introducing people who may not know very much more than that to the wonderful sophistication, history and legacy of this ancient culture.”

Graves, the head of the EES, an organisation founded by the Victorian explorer Amelia Edwards, concurs about Tutankhamun’s appeal. “It’s a gateway, it’s a hook,” he says.

For us as Egyptologists, finds don’t have to be so spectacular. They can be one teeny weeny fact that puts the history of ancient Egypt on its head

Salima Ikram, a Pakistani Egyptologist at the American University in Cairo, thinks the importance of Tutankhamun as a Pharaoh is often overlooked. To her, he is mistakenly dismissed as a young ruler whose policies were fully shaped by his advisers. He ascended to the throne at nine and died at 19.

“Tutankhamun was in fact one of Egypt’s most significant kings, though his successors tried to erase him and take credit for his work,” Ikram says. She notes how he reinstated the cult of the god Amun-Ra and reopened his temples, following his heretic father Akhenaten’s “17 mad years” in power, during which conventional religious practices were abandoned.

“Tutankhamun brought back balance and a sense of security to a country that had lost it,” says Ikram, who believes that he “wasn’t entirely a pawn”. She contextualises this by saying that people grew up much faster in the ancient world. “By the time he was 13, I’m sure that like any young man he was making his muscles – intellectual as well as physical – felt.”

The splendour and volume of the 19-year-old’s funerary goods will soon be on display as never before. They will be housed just outside Cairo in the Grand Egyptian Museum, which is expected to open early next year. Graves, of the EES, says it will be a “wonderful repository” of Egyptian culture. “I’m excited to see the ways in which Egyptians use that heritage to communicate ancient Egypt to the rest of the world.”

Although Ikram thinks the Tutankhamun collection is a wonderful boon to Egyptology, she explains that gold and other precious objects aren’t everything. “For us as Egyptologists, finds don’t have to be so spectacular. They can be one teeny weeny fact that puts the history of ancient Egypt on its head and puts us all scuttling back to look at everything with a new piece of evidence that changes what we thought or what we knew.”

Rosenow, the Oxford University academic, agrees. While celebrating the wide interest that Tutankhamun continues to generate, she advises people to remember just how much work archaeology requires. “You don’t run into a temple, grab a goblet and run out again,” she says.

In a rare voice recording from a lecture he gave in 1936, Carter, who spent a decade working on Tutankhamun’s tomb, compressed the wonder of his initial discoveries into a few short minutes. Of all the thousands of items he and his team uncovered, he says the flowers found in the Pharaoh’s coffin stood out most of all.

“Amid all that regal splendour, everywhere the glint of gold, there was nothing so beautiful as those few withered flowers. They showed us what a short period 3,300 years really was,” he said.

To commemorate this, Rosenow has commissioned a local florist to recreate the wreath of olive leaves and cornflowers, which measured roughly 10cm in diameter, according to information contained in the Carter archive. At a small ceremony on Friday, it will be placed in the exhibition. Rosenow does not want it to be a “glitzy” affair. “I think the wreath brings in the human element,” she says.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks